CHICAGO

Incorporated 1789

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

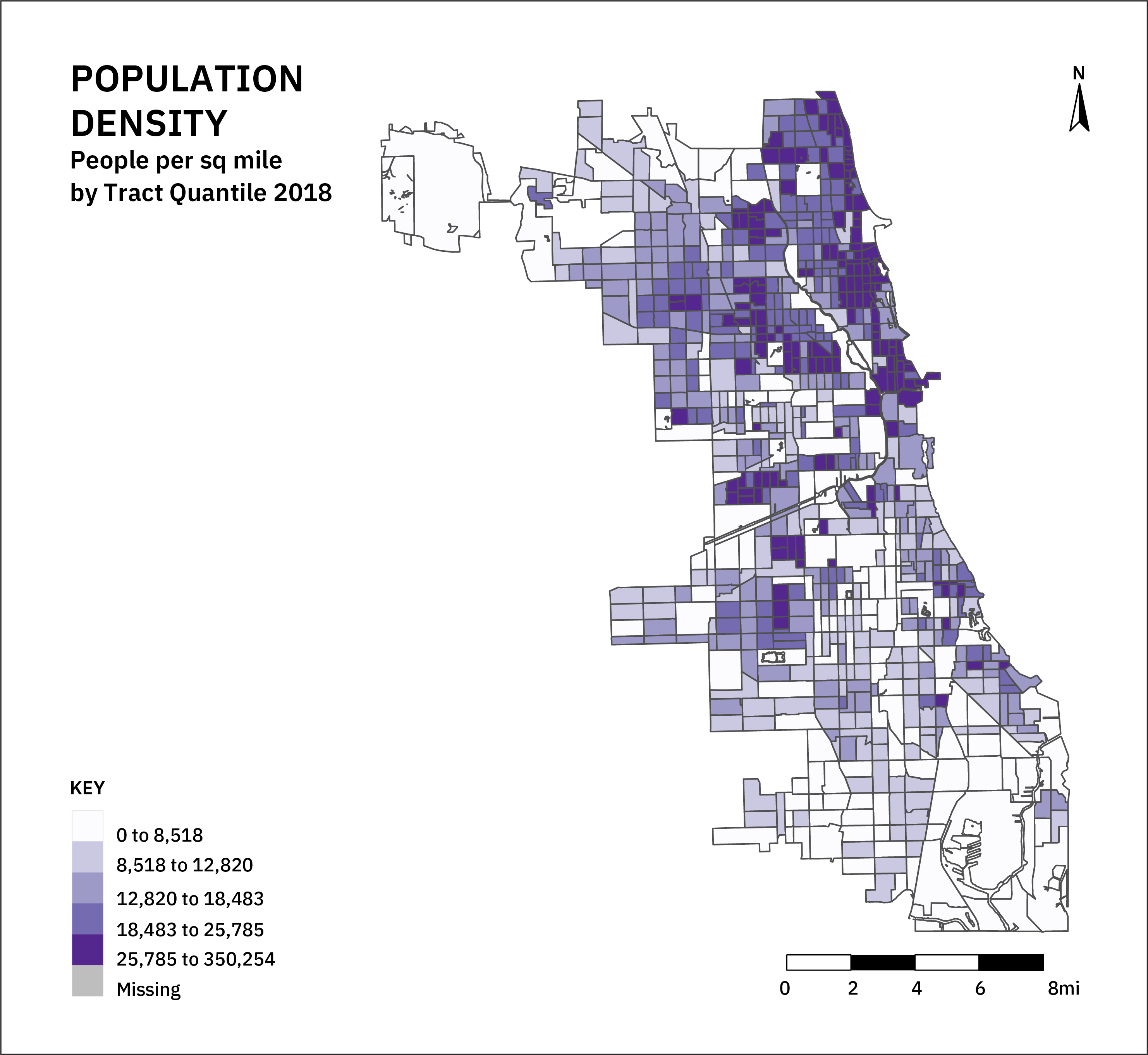

- 234.2 sq miles

- 2,718,555 Total Population

- 11,956 People per sq. mile

- 0.6% Forest cover

- Temperate Grasslands, Savannas, and Shrublands

- 3.4% Developed open space

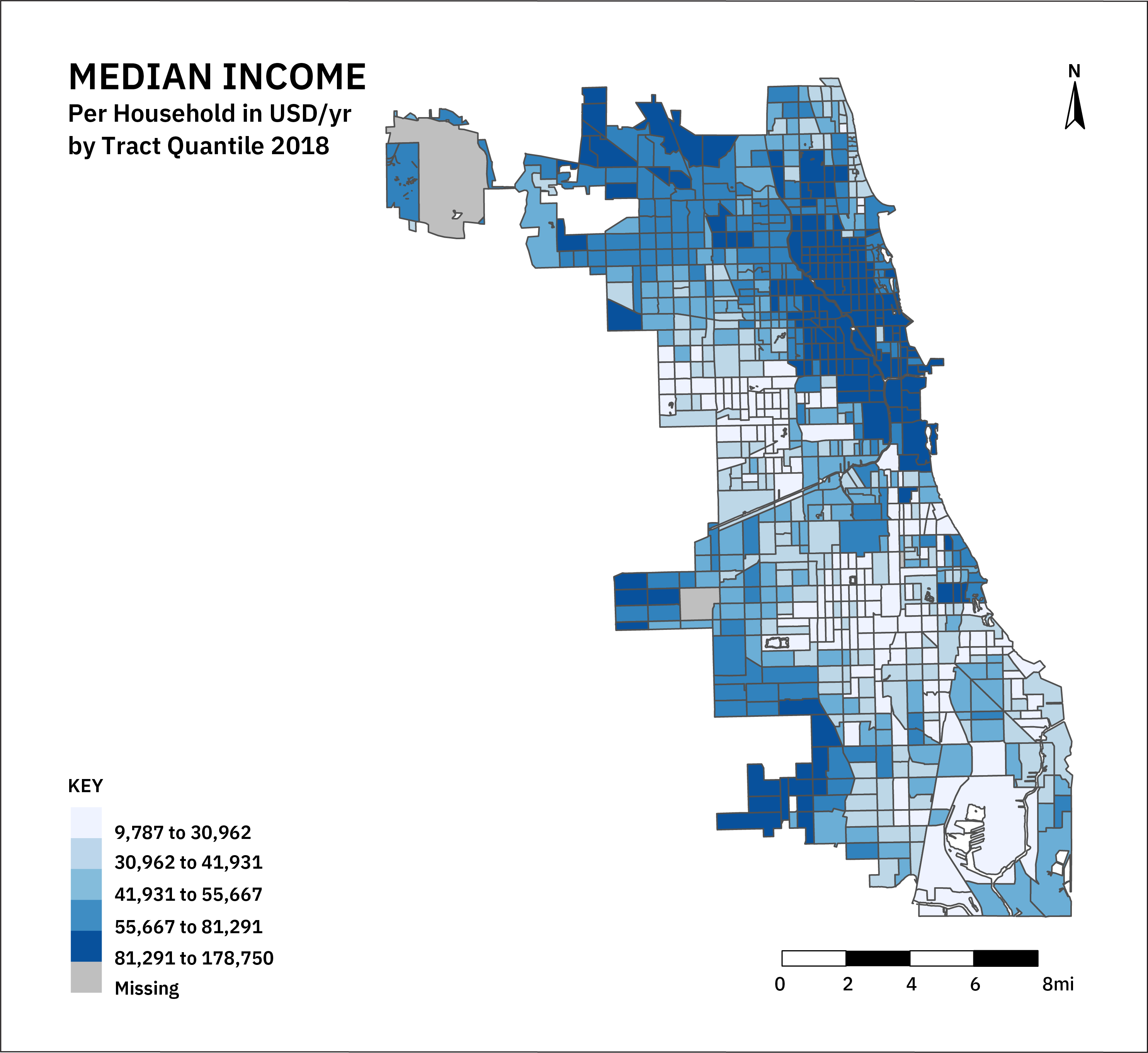

- $55,198 Median household income

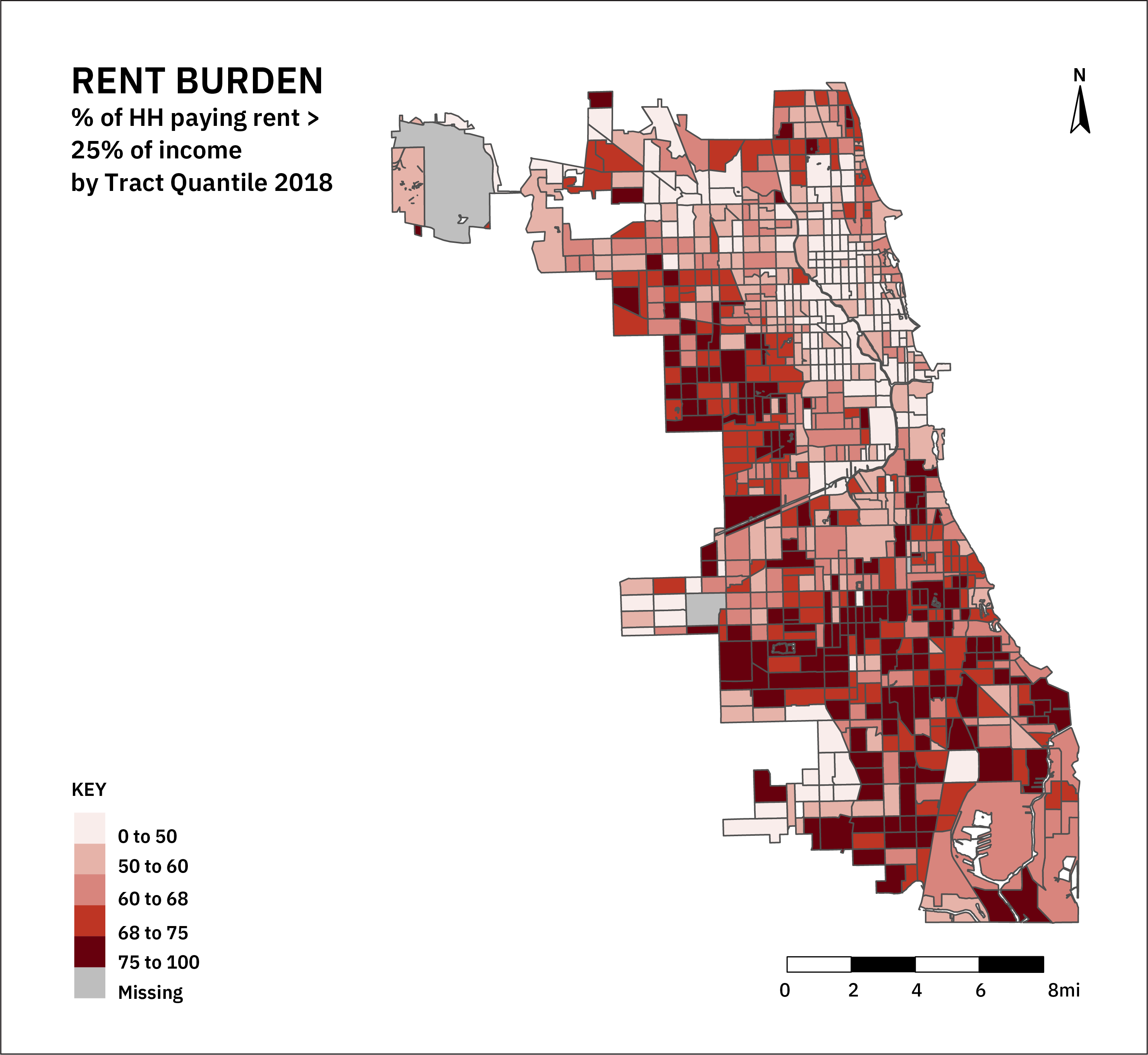

- 61.5% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 15.5% Live below the federal poverty level

- 12.6% Housing units vacant

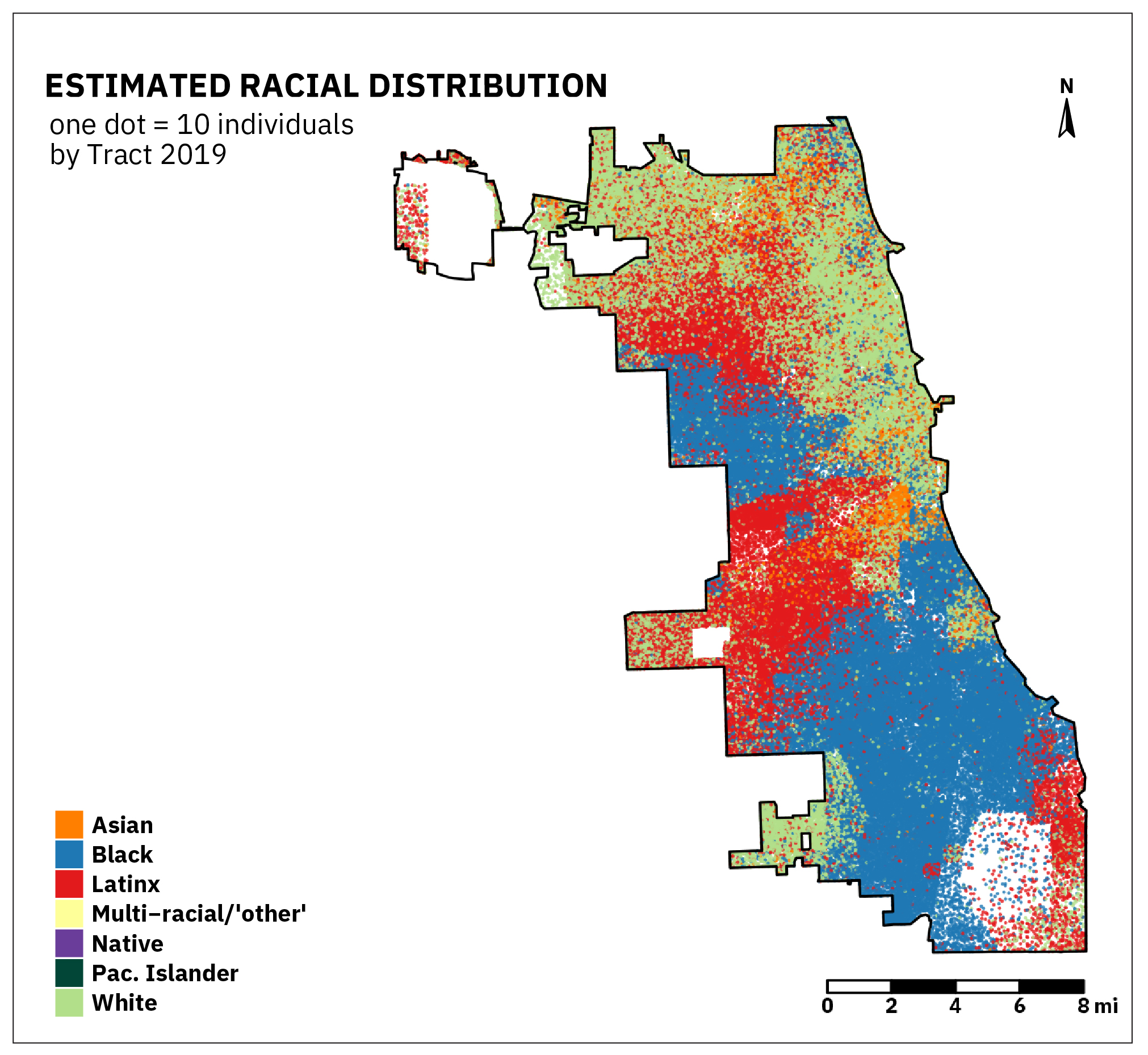

- 0.1% Native, 33.3% White, 29.2% Black, 28.8% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 6.5% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The city of Chicago occupies the homelands of numerous Native nations, including Potawatomi, Peoria, and Miami peoples, and continues to serve as a hub of Native organizing. As the largest metropolis of the midwest, Chicago has been shaped by its role as a hub for regional agricultural and natural resource economies and heavy industrialization. As a major destination for global immigrants and Southern Black folx, Chicago has a high degree of racial and ethnic diversity in an intensely segregated city.

Chicago has also served as a key site of development of social movements and theories on urban transformation and justice. The city famously rerouted the Chicago river to prevent sewage flow into its drinking water source of Lake Michigan, a solution made precarious by climate change. The city faces ongoing challenges around racial disparities and uneven exposure to climate hazards, especially heat waves.

Green Infrastructure in Chicago

Chicago is unique among the cities we examined for differentiating between natural and engineered green infrastructure in its Green Stormwater Infrastructure Strategy. The GSI plan defines natural GI using an integrated concept and engineered GI using a stormwater-focused concept. Neither the cities Sustainability Plan or Adding Green to Urban design plans define GI. GI planning in Chicago is further complicated by the fact that the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago oversees significant portions of the city's sanitary and water supply infrastructure.

Types of GI in Chicago span all three of our major categories and include designed elements such as green roofs, rain gardens, and permeable pavers. However, plan definitions do not consider a diverse set of open space and ecosystem types.

Functionally, GI is managed to provide environmental functions, dominated by a fairly limited set of hydrological services.

Despite the care to differentiate broadly between natural and engineered GI, the benefits of GI remain weakly defined, focusing only on property values and energy conservation.

Key Findings

GI plans in Chicago make almost no mention of equity or justice issues and do not define equity or justice. There are some attempts to include affected communities in the planning lifecycle, especially in the Sustainability Plan and the Green Urban Design Plan. While the city has developed an extensive GI based stormwater management program, there does not appear to be a comprehensive or systematic GI planning approach in the city.

25%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

25%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

75%

seek to address climate and other hazards

75%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

50%

explicitly refer to justice

75%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Chicago through Maps

Chicago is a highly developed urban area with several large green spaces concentrated along Lake Michigan and a few others dispersed across the city. Population density varies considerably and appears to have an inverse relationship with rent burden and vacancy, which also correlate with racial composition which is segregated throughout the city. These patterns speak to the long histories of urban renewal and disinvestment in marginalized communities.

How does Chicago account for Equity in GI Planning?

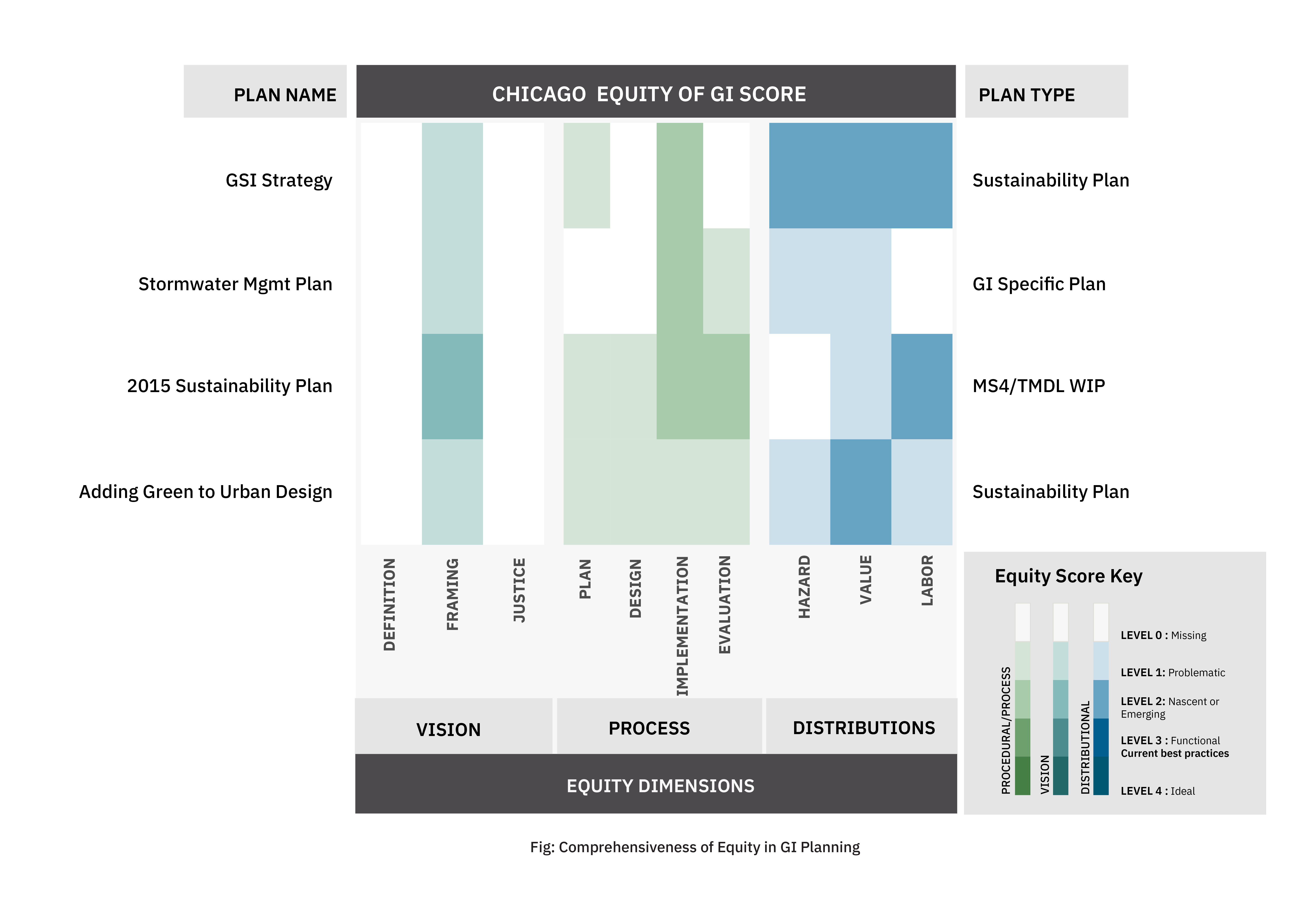

Chicago GI plans are startlingly absent of any substantive mentions of equity but still have significant equity implications. No plans in Chicago addressed all ten dimensions of equity we examined. Across plans, there are weak commitments to participatory planning, with some unspecified commitments to interdepartmental equity in GI implementation, although evaluation remains nascent or problematic.

There were no definitions of equity or justice across the four plans examined. Framings of equity were weak and general across plans. One exception was found in the sustainability plan which describes a vision of accessible employment and economic development supported by public investments in infrastructure supporting health and cost savings. Considerations of justice were absent across plans.

Chicago GI Plans, and in particular the GSI strategy, intend to use GI to address a range of climatic hazards, (notably heat, flooding, waterborne diseases, and water pollution) and to add many different types of value to the urban landscape. Yet, they fail to discuss any downsides to these initiatives, or how values may differ between communities. Plans do not link the admirable high level goals of creating meaningful and well-compensated employment opportunities to GI programs and initiatives.

Envisioning Equity

No GI plans from Chicago define equity or justice. Overall framings of equity are also weak. The Sustainability Plan offers a universal vision of development and employment but does not address existing disparities or their historical causes. The GSI plan similarly seeks to modernize infrastructure systems for the public welfare but contains no discussion of disparities in service levels or other social inequalities that such a vision would need to address to be successful. Failing to adequately frame or envision equity in current GI plans is likely to reinforce existing injustices within the city.

Procedural Equity

The procedural equity of GI in Chicago is generally weak. While there is some emphasis on involving diverse stakeholders in implementation, there is no overall framework for meaningful collaboration or consent for GI programs or initiatives. Overall, GI strategies appear driven by top-down decision-making, with community involvement more of an afterthought. The Sustainability and Greening Urban Design Plans extend considerations of involvement in all four procedural dimensions, but involvement is limited to city agencies, despite an emphasis on the need for citizens to lead implementation. Such an approach places the burden of success on city residents without meaningfully including them in the planning and design of programs and initiatives. Chicago’s otherwise well-developed GSI Strategy makes mention of a multi-stakeholder process but it is not clear if and how affected communities were involved in this process. The Sustainability and Green Urban Design Plans reference the involvement of stakeholders and partners, but appear to have input from city agencies and interested professionals exclusively. The MS4 plan covers its regulatory requirements for coordinated implementation but limits community involvement to being targets of outreach. While it lists the 311 complaint process as a means for community evaluation of projects, it is not clear how that information will be used to revise approaches. Lastly, while the GSI strategy creates an interagency process for the review of capital investments and projects, the process is not clearly described or transparent.

Distributional Equity

Although the overall GSI strategy considers the distributional dimensions of GI value, hazard, and labor, it fails to deeply discuss the uneven distribution of present hazards or value or the potential downsides to using GSI for property value improvements. Discussion of distributional equity in current plans varies considerably, and, as in other cities, completely omits impacts on renters. The Sustainability Plan has a high-level goal of making well-compensated employment available to all city inhabitants but this goal is not linked to GI. While Chicago is somewhat unique in requiring that Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) be written for the maintenance of specific GI projects and facilities, it is not clear how these agreements between agencies and residents will be enforced.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Chicago has pivoted in 2020 to address equity issues through its ‘We Will Chicago’ planning process. Yet despite a careful articulation of a Green Stormwater Infrastructure planning concept and the elaboration of ‘green design’ principles, Chicago plans do not appear to provide a cohesive framework for integrating diverse ecological and technological elements into a city-wide GI system. Current GI plans have largely failed to even define equity, let alone detail processes of how diverse communities will have meaningful input with city agency initiatives, or how their values and concerns will be addressed in city-led planning. In light of the ongoing demands from a diverse range of community groups for the city to meaningfully address equity and justice in GI planning, Chicago will need to re-examine its planning legacy and its shortcomings in this arena. Below we provide recommendations on how to facilitate this process.

Community Groups

Existing GI initiatives and plans appear to have largely failed to address the needs of disenfranchised and marginalized communities. The current push to include equity in the city’s comprehensive planning process should provide space for community-led planning efforts in diverse domains. While ‘green infrastructure’ as a stormwater planning concept has been extensively applied by city agencies through the City’s green roof and stormwater programs, significant improvements can be made to ensure that the multiple benefits and functions of diverse green elements throughout the city can deliver the benefits that communities need and desire. Fortunately, Chicago has demonstrated a capacity for this type of work through a long history of community organizing, including the formation of the original rainbow coalition, and other social movements within the justice-oriented and class-conscious struggle continuing to this day.

1. Framing Equity and Justice Issues

Community groups can and should provide vital contextual definitions and framing of equity and justice issues in Chicago as part of the current push to address equity in planning in the city. These visions for an equitable urban future must be elevated and amplified so they cannot be overlooked by the city agencies and planners who are responsible for implementation While the ‘We Will Chicago’ process provides formal mechanisms for this process, the degree to which community groups can coordinate their campaigns outside of municipally sanctioned processes will determine the measure to which historically oppressive institutions can be transformed or abolished.

2. Shifting Narratives around Housing, Renewal, and Environmental Justice

Like many cities continuing to transition into a post-industrial economy, the significant rent burden in Chicago continues to be exacerbated by a speculative real estate market overbuilding luxury housing. Combined with narratives on the centrality of entrepreneurship and innovation, longer running struggles for affordable quality housing are obscured by the dominant narrative that focuses solely on increasing incomes. In such cases, Environmental Justice is Housing Justice, as household and neighborhood toxins are primarily sourced from buildings, transportation, and power generation infrastructure. Bringing a broader concept of greening and green infrastructure into discussions on Housing and Environmental Justice allows for a more multi-dimensional concept of Just Transitions to take hold, building momentum for positive change and ‘greening in place.’

3. Building Community Power

Chicago has long served as a testbed for the limits of institutional power structures to meet the needs and demands of communities that are not well represented in the city’s decision-making bodies. While the city continues to debate methods of electoral reform, it is clear that one of the epicenters of ‘machine politics,’ in the USA, will not change without the continued building of community power around issues of structural reform. In this sense, the ‘We will Chicago’ process can be a vehicle for community power building. To do this, it must demand the creation and inclusion of substantive mechanisms for community-led planning. These, in turn, could translate into new forms of participatory and collaborative governance.

Policy Makers and Planners

The current push for a city-wide plan centering ‘equity, diversity, and resiliency’ must embrace a robust concept of equity and justice if it is to meaningfully address the legacies of systemic racism in the built environment and beyond. While the general principles of equity and justice detailed in our framework page can inform this process, we hope that it is clear that these principles call for the meaningful inclusion of affected communities in the decisions that shape their lives. Policy makers and planners have multiple opportunities to change existing institutions and planning procedures. To aid in this process, we identify several recommendations below.

1. Opening Planning to Equity and Justice

The current effort to center equity, diversity, and resiliency in the City’s city-wide planning efforts is a welcome change to existing planning practices. However, as we have observed, these words can often be used without any meaning. To avoid using them as simple buzzwords in planning, planners and policy makers should commit to an open dialogue around what equity and justice entail and what they do not. As the city has been the epicenter of numerous community organizing initiatives, there is an opportunity for extremely rich dialogue with community organizations about the meaning of equity and justice in the context of Chicago’s history and current struggles. These dialogues should result in robust and meaningful definitions of equity and justice that guide concrete actions on behalf of city agencies, as well as other means of democratic urban governance described below.

2. Democratizing City Planning and Agencies

Chicago has long struggled with corruption in city agencies and budgeting, which some see as an indication of a deficit of democracy. To make city greening initiatives more equitable and just, they must become more genuinely democratic through genuinely inclusive planning. Given current plans are not inclusive, there is a need to build inclusive processes. Focusing on initiatives that have tangible outcomes, like neighborhood-level budgeting, and those which improve neighborhood environmental quality can give communities faith that democratic planning can improve their lives.

3. Examining differential vulnerability and exposure to hazards

Despite being well documented, a major gap in Chicago GI plans is a lack of attention to the social distribution of hazards, which has been well documented. The disregard for the distribution of hazards is compounded by the failure to acknowledge the lopsided distribution of the consequences of those same hazards, or what some call differential vulnerability. Planners should address these highly salient issues in collaboration with affected communities.

4. Getting Ahead of Green Gentrification

Chicago has been recognized as a green infrastructure leader, primarily due to the scope and history of its green roof programs and stormwater infrastructure innovations. However, the relationship between green development, GI, and the potential for housing displacement caused by upscale development has not been addressed in Chicago plans. Given the extensive inequalities in housing access and affordability in the city, planners and policymakers have an opportunity and obligation to address housing affordability while solving environmental challenges.

Foundations and Funders

Foundations and funders can play a key role in building community power amidst the dearth of participatory planning practices in Chicago by supporting community organizing in support of community-led planning efforts. Organizations and community-based non-profits have already articulated diverse GI needs, and there is ample space and opportunity for greening given the volume of vacant lots in marginalized neighborhoods. However, existing GI plans do not name many organizations despite an explicit intent to partner with environmental groups and NGOs. This indicates a need to develop organizational capacity so that community-based organizations can participate in planning processes.

- Addressing Legacies of Injustice through Proactive planning

There is an opportunity to link existing city initiatives like the vacant lots program with the equity-focused Comprehensive Plan. However, doing so will require sustained investment in community organizing, including the creation of venues, space, and support for meaningful community engagement.

Closing Insights

Despite almost a decade of progress in implementing green roofs and a variety of stormwater-focused green infrastructure features throughout the city, Chicago Green Infrastructure Planning remains largely silent on issues of urban equity and environmental justice. Current planning initiatives present multiple opportunities to build community power but will require a restructuring of existing decision-making processes, and dedicated support for diverse and intersecting community organizing initiatives.

Resources

A guide and compilation of materials on the issues related to green infrastructure and equity in the United States including our case study cities.

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Community and Grassroots Groups

A list of grassroots organizations working on equitable GI encountered during the course of the project.

Other organizations and initiatives working on equitable green infrastructure nationally or within study cities.

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.