New York City

Incorporated 1624

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 468.2 sq. miles

- 8,443,713 Total population

- 28,110 People per sq. mile

- 4% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 5% Developed open space

- $60,762 Median household income

- 15.6% Live below federal poverty level

- 64% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 9.2% Housing units vacant

- 0.2% Native, 32.1% White, 21.8% Black, 29.1% Latinx , 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 214% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The City of New York occupies the homelands of the Lenape people who continue to fight for recognition alongside other Indigenous Nations. The city occupies one of the most productive estuarine systems in the world and has long been a global center of trade and finance, which included mass importation of enslaved Africans.

Aging infrastructure, high income inequality, and large racial disparities in health outcomes pose significant challenges for a city with a contested municipal budget, increasingly governed through participatory approaches. Since Hurricane Sandy, the city has been the epicenter of federal investments in coastal infrastructure. The city has grown rapidly in the last several decades, regaining and surpassing inhabitants lost in mass emigration that began in the 1960s, with a significant portion of this growth occurring in vulnerable coastal zones.

Green Infrastructure in New York City

New York City has numerous, sizable, and ambitious green stormwater infrastructure programs that are integrated into city-wide tree planting initiatives. While the city also has extensive source water protection areas and programs, these are only tangentially referred to as part of the city's green infrastructure. A central tension in GI planning in NYC is the inclusion of softer coastal defenses, as well as the challenges of rising sea levels and associated extreme weather events.

These intersecting challenges are reflected in diverse elements of the city’s GI plans, yet plans do not include parks, trails, farms, gardens, waterfronts, parkways, ecosystems more broadly, or blue-green networks. For example, the Staten Island Bluebelt was labeled as a corridor in our analysis. The city’s GI plans primarily deal with controlling combined sewer overflows and regulating many aspects of urban hydrology in addition to supporting carbon sequestration. Despite the limited functional focus of GI in NYC, city plans tout the diverse benefits of GI projects.

Key Findings

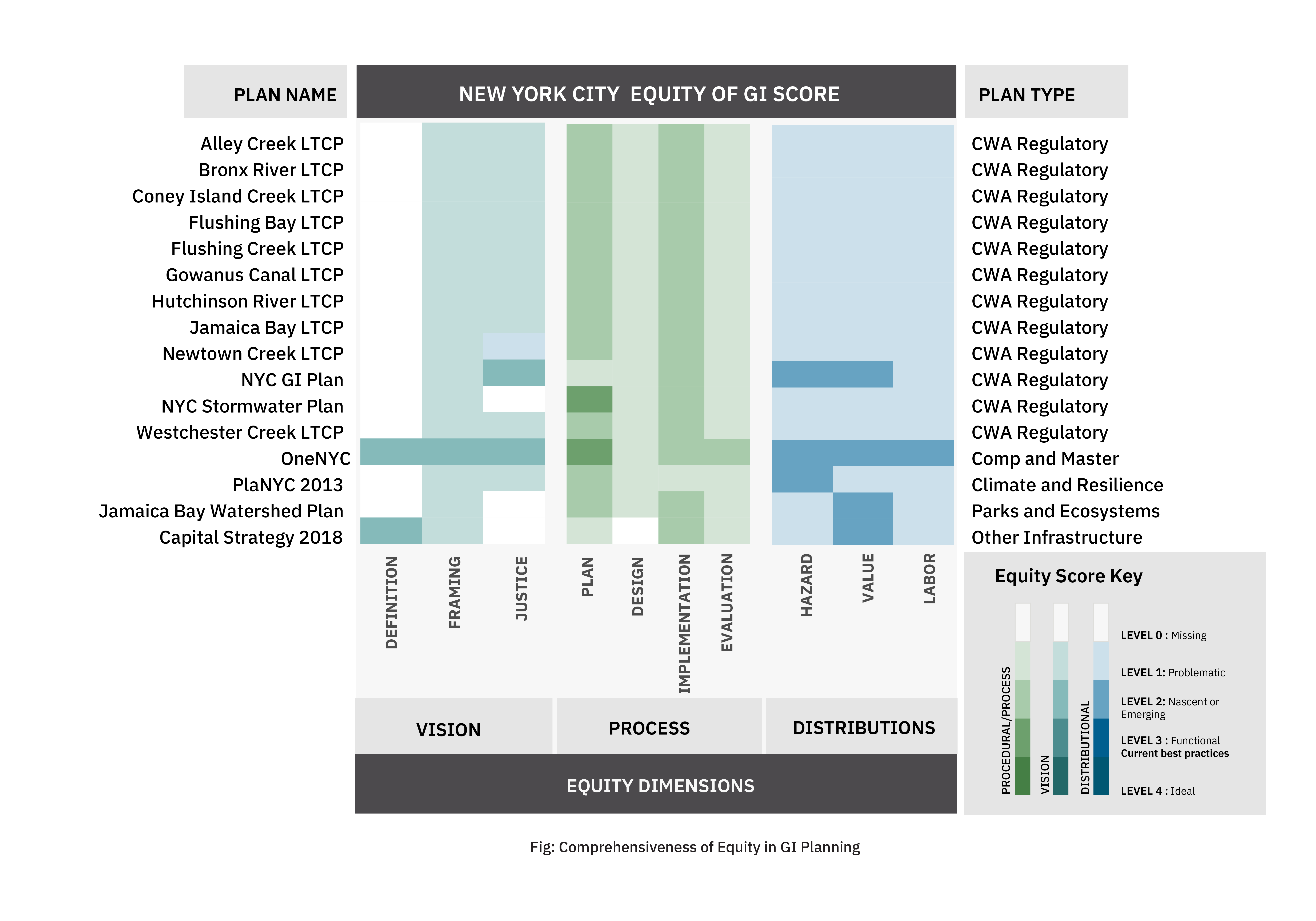

NYC GI plans are largely silent on equity issues, with few definitions, limited mechanisms of community engagement, and weakly developed distributional aspects. Promising exceptions include the public participation mechanisms in the initial stages of the city’s overarching Stormwater Plan and OneNYC. OneNYC, the city’s combined comprehensive and sustainability plan, was one of the few plans that addressed all ten dimensions of equity in our scoring tool.

Of the plans in our analysis...

13%

explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

19%

recognize that some people are made more vulnerable than others

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

13%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

13%

define equity

81%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

13%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

New York City through Maps

New York City is the largest and densest city in the United States, and yet retains several large park areas and numerous small open spaces. The city contains multitudes of diverse communities and neighborhoods, and yet remains highly segregated by income, race, and rent burden. Highly varied vacancy rates are associated with both high-rent districts and areas of entrenched poverty.

How Does New York City Account for Equity in GI Planning?

Overall, equity is weakly addressed in plans, with few definitions provided. The city’s numerous plans for compliance with Clean Water Act regulations consistently mention environmental justice communities but in a check-the-box approach. Framings of the social impacts of GI are generally underdeveloped. The OneNYC plan stands out for addressing all 10 dimensions of equity analyzed with our evaluation framework, and yet does not exhibit many best practices.

Mechanisms of community engagement are largely underdeveloped, with very few opportunities for communities to be involved in the design and evaluation phases of GI programs. Despite consistency in most plans in terms of public outreach during the planning process and in implementation, they do not reflect current best practices.

NYC’s GI plans consistently seek to minimize hazards and add value with GI. However, these approaches do not reflect the concerns or needs of affected communities and, therefore, are largely problematic. Labor issues are also poorly addressed.

Envisioning Equity

Both OneNYC and the Capital Strategy (2018) define equity, emphasizing the need to improve historically underserved communities and address uneven distributions of environmental hazards. These deficit-oriented definitions, while well-intentioned, do not unpack the causes of socioeconomic marginalization. Furthermore, they do not articulate the need for targeted communities to be involved with and shape the processes of decision-making for resulting projects and programs. Justice considerations are mentioned in most plans but are only addressed with any detail in the City’s GI plan and OneNYC. In both instances, EJ communities (not defined within the plans) are targeted for additional, but unspecified types of engagement and prioritized as targets for GI programs. These types of top-down approaches of community redevelopment and revitalization are at the core of many concerns around GI and need to be addressed.

Procedural Equity

NYC’s OneNYC plan and city-wide Stormwater Plan involved large and multi-pronged processes of public engagement in their formative stages. These processes of public engagement serve as examples of best practices but do not reflect current planning theories.

OneNYC’s survey, which sets the overall plan priorities, appeared to force respondents to choose among predetermined options rather than begin with open-ended listening sessions or town hall meetings, as in other cities. In addition, the survey methods did not include an analysis of the socioeconomic or demographic composition of the respondents. Lastly, there is limited documentation of the type and content of the engagement meetings held during the plan’s formation.

The city-wide Stormwater Plan involved extensive public comment periods and sought to inform affected communities of plan activities through various means, but lacked documentation and mechanisms for sustained community engagement. Compliance plans were largely formulaic in their approaches, appearing to follow the templates set by the EPA. NYC’s GI strategy was lacking in specificity and weak on procedural inclusion at all stages. The lone exception was a nod towards the necessity of community engagement for the successful implementation of programs and projects.

Distributional Equity

Despite extensive, ambitious, and well-resourced city-wide programs, the distributional elements of GI planning in NYC remain largely problematic. Except for the OneNYC, city-wide GI strategy, and the 2013 Resilience Strategy, plans focus on a very narrow range of hazards, primarily stormwater management and water quality issues. The aforementioned plans provide a more detailed approach for multiple climate-related hazards but do not acknowledge how the city’s strategies may shift risks or have other unintended consequences.

The value of GI is discussed primarily in terms of improving the cost-effectiveness of the city’s infrastructure investments, with some minor descriptions of the multiple values provided by GI systems. It is not clear how the city’s limited types of GI will reflect the desired values, or how the city will address potential housing displacement from targeted community improvements.

Plans are mostly silent on labor issues. The LTCPs and the city-wide GI strategy embrace a logic of enabling groups to pursue grant funding, without making concrete commitments to hiring goals or specific labor practices. Non-compliance plans emphasize the role of volunteers in facility maintenance, with the 2013 Resilience Strategy going so far as to create a volunteer-to-wage employee pipeline. The OneNYC plan provides the most detailed description of labor requirements of the city’s GI programs, going so far as to explicitly state the need to hire an estimated 360 individuals for non-union and minimum wage entry-level positions, albeit with some opportunity for climbing the career ladder. At the same time, most high-value design and construction work will benefit existing city contractors and private sector companies. These approaches stand in stark contrast to other city programs that provide targeted training and unionized labor (e.g. the City’s energy efficiency programs). There was reason for hope in OneNYC because the city recognized the stagnancy of wage growth outside of the finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) industries, and the need to address structural economic inequality through public sector programs and legislation. However, these acknowledgments were not reflected in the plan’s descriptions of the city’s GI programs.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

New York City is in many ways an equity enigma. The Office of Citywide Equity and Inclusion has been in existence in some form for over 30 years. Prior and current administrations have promised to increase equitable opportunities for economic advancement and in mitigating climate hazards, especially in the post-Sandy, post-2008 financial crisis, and the looming post-Covid-19 era. Despite these high-level, institutionalized commitments, there are opportunities to improve upon equity concepts and practices in NYC’s GI planning. Based on our findings, we identify several key areas for advancement below.

Community Groups

New York City is a major urban center of social justice organizing. Current movements emphasize the need for economic and racial justice. They also call for a just transition, which would include revitalizing green manufacturing and addressing long-standing environmental justice issues. The city’s reform planning history is evident in its parks system, with organizations like the Central Park Conservancy grappling with the racist histories of park creation and current issues of violent policing. Ongoing green revitalization, such as the High Line project, has also faced criticism for contributing to housing displacement and has led to an evolved conversation on the relationship between urban revitalization and community stabilization. Organizations like WeACT for Environmental Justice have led the charge to responsibly remediate brownfields, address intersecting concerns around housing, and support affordable and accessible housing. Below we provide several recommendations for how community groups can advocate for greater control over city-wide greening initiatives.

1. Treating GI as a City-wide System Supporting Community Well Being

New York communities face incredible disparities in exposure to climate-related hazards and pollution which require proactive approaches to transforming technological systems and greening the urban environment. The city’s current GI programs are limited in scope and are not conceptually robust enough to support the type of transformative thinking required to provide solutions at scale.

Community groups can advocate for a more systematic approach to urban greening that does not fetishize particular GI installations or parks, instead, focusing on providing GI as a public good while also prioritizing those communities most in need. Since the city has already adopted this approach with regards to green stormwater infrastructure and park planning independently, communities can advocate for joint city-wide planning that would include other currently siloed initiatives such as the city’s nascent citywide bike plan (which currently does not mention GI). Only through creating comprehensive green space networks of diverse GI elements in combination with massive reductions in pollution from transportation, manufacturing, and power generation (greening industrial infrastructure) can the EJ concerns of communities be comprehensively addressed.

2. Embedding Equity in Planning

New York City GI Plans have a long way to go to build the means for effective and substantial community engagement and control. A more expansive conception of GI will lend itself to GI becoming more relevant in existing efforts to achieve environmental justice in the city. A substantive evolution of mechanisms for communities to guide planning efforts will also be required.

Drawing upon principles in equity planning theories, communities should advocate for binding mechanisms that enable communities to control city agency activities, compensation for the labor required to have oversight over city agencies, diverse, accessible, and inclusive engagement meetings, and the building of technical expertise within affected communities. The acquisition of such expertise is part of wealth-building as the skilled labor practices required for successful and effective GI systems are recruited from the ranks of community members. Existing participatory budgeting processes are a promising vehicle to begin this transformative approach towards planning, and should be more deeply embedded in the community forums and decision-making processes that allocate the city’s tremendous resources to provide for the general welfare of its residents.

Policy Makers and Planners

Current calls to address systemic racism and injustice in city decision-making and policy, primarily through the standing Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equality and the Racial Justice Commission, should extend to the city’s extensive green infrastructure programs. Given that both the Taskforce and Commission are in their formative stages, we offer several considerations for these bodies and existing city agencies involved in the city’s green infrastructure programs. Below we elaborate on how current plans could address issues in their implementation and outline considerations for the evolution of city-level green infrastructure policy.

1. From “Planning For” to “Planning With”

NYC plans have an admirable focus on centering environmental justice communities as the targets of GI programs. Yet, mechanisms for substantive engagement over the lifecycle of GI policies and programs are not built into current planning practices. Policy makers and planners should engage and collaborate with affected communities throughout the entire planning process. Collaborative actions should include: accepting open-ended public comment in the earliest stages of planning, creating accessible meeting spaces, establishing implementation safeguards, and designating communities as the ultimate evaluators of GI program effectiveness.

2. From Ecological Security to Community Well-being Through Citywide GI

New York City’s GI plans have largely been balancing the needs of stormwater management against climate adaptation and sea-level rise. These necessary activities should be put in a larger context that addresses the overall quality of life for city residents. This systematic city-wide green infrastructure approach goes beyond coastal defense and stormwater systems. It includes redesigning roadways, park systems, green networks, urban agriculture, and trail systems and embedding ecological elements much more firmly into the urban landscape, while still providing the proposed benefits in current plans.

3. Defining Equity and Justice

New York City GI plans do not adequately define equity or justice issues. Existing definitions need to be updated to reflect the legacies and ongoing practices of dispossession and marginalization. A deeper understanding of ecological justice in the city requires addressing the city’s dispossession of Native people’s lands, the role of racism in structuring urban space and city policies, and the transformation of existing decision-making processes to give voice and power to those who have been, and continue to be, marginalized by current practices.

Foundations and Funders

Many foundations and nonprofits are active in addressing the city’s long-standing environmental and social justice issues, including many that focus on building grassroots power and organizing capacity. These efforts intersect with the city’s green infrastructure policies in several ways, especially with regard to how GI policy supports redevelopment, brownfield remediation, climate resilience, and access to environmental amenities. Current large-scale social movements and grassroots political pressure present opportunities to significantly advance discourse and organizing so that the root causes of environmental degradation and injustice can be addressed. This includes advancing long-standing efforts of the Lenape community to recognize and restore their cultural relationship with local land and water systems.

1. Centering Governance and Right Relations in Discussions on Indigeneity

Despite increased awareness about the Indigenous history of the area now called New York City, public discussion on the role of Native peoples has been largely relegated to the problematic narrative of ‘cultural heritage.’ As many Indigenous peoples and leaders have made clear, recognizing Native relationships with land requires recognizing Native governance over land, and the ways that governance was illegally usurped through militant dispossession and/or negotiated by treaty. Given that there is no definitive account of rightful treaty negotiation, New York City must be considered to be on unceded and unsurrendered territory. At a minimum, this fundamental injustice must be addressed with the Lenape who have never accepted the loss of their lands. Given the extreme uphill battle such recognition entails, foundations and funders can support a grounded approach towards ecological justice by supporting Indigenous organizations seeking this transformative justice.

2. Intersectional Green Infrastructure in a Just Transition

Building a solid foundation for addressing equity work in cooperation with grassroots organizations requires overcoming the siloing often present in environmental justice work. Disparate groups working on accessibility of parks, addressing legacies and present realities of structural racism, and housing and labor justice, could find common ground in seeking deeper transformations in city decision-making systems and the nature of the built environment. A Just Transition framework contains guidance for funding coalitions that are endeavoring to address intersecting concerns. Green infrastructure is a vital component of this aim.

Closing Insights

New York City’s extensive GI programs present many opportunities to address ecological justice and equity. Still, current approaches in city-led plans omit key aspects of equity. There is much work to be done to address this incomplete conception of GI. Our recommendations to focus on systemic and intersectional issues have the potential to dramatically reshape the city’s GI programs so that transformational approaches are centered. However, this will require a willingness and sustained effort by city agencies and policy makers to shift towards a community-led planning model, supported materially by the city, to realize the potential benefits of a city-wide Green Infrastructure system.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.