ATLANTA

Incorporated 1837

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

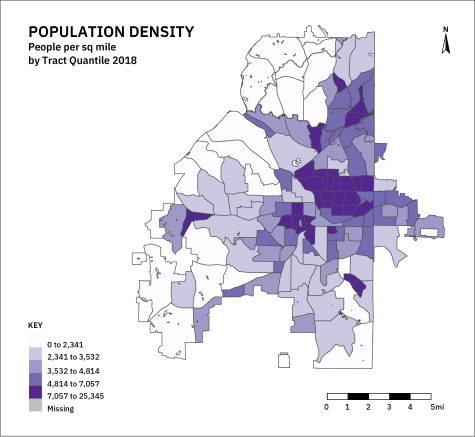

- 135.6 sq. miles

- 498,000 Total population

- 3,673 People per sq. mile

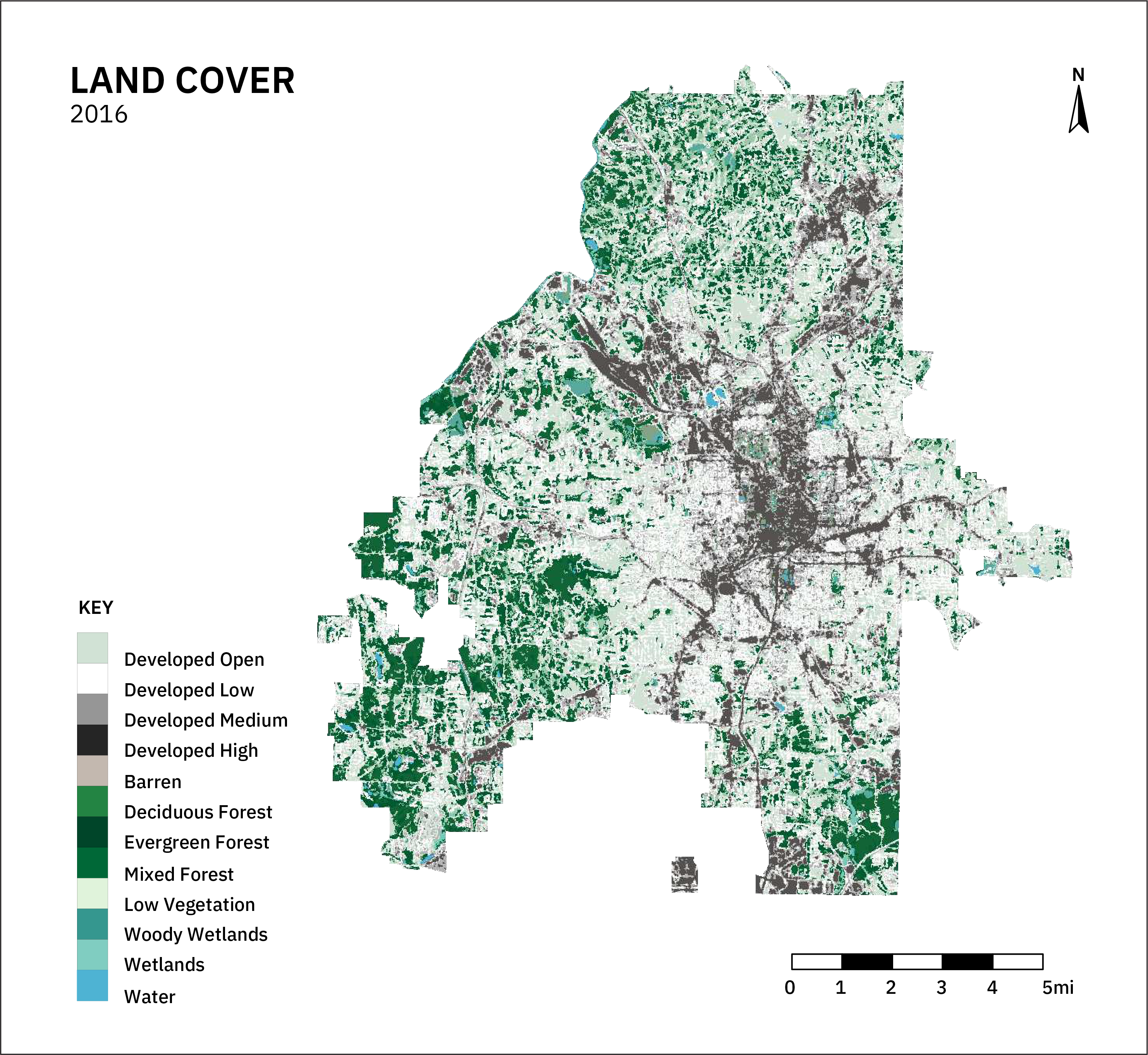

- 26% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 26% Developed open space

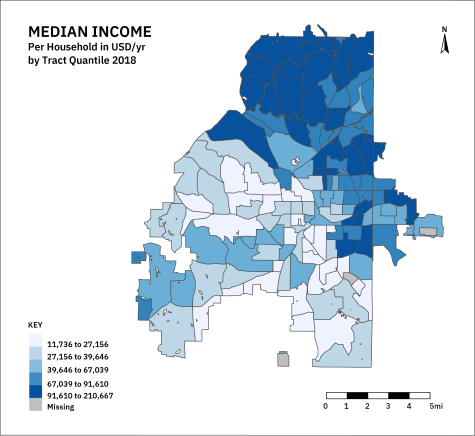

- $55,279 Median household income

- 21.6% Live below the federal poverty level

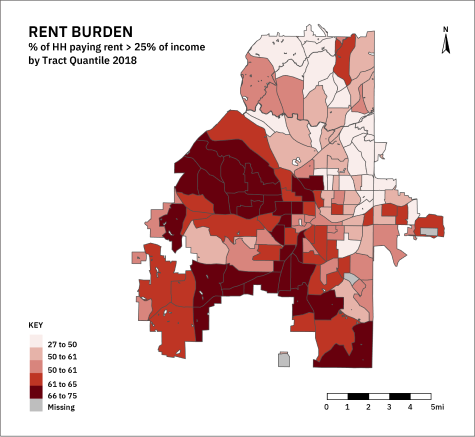

- 63% - Estimated rent-burdened households

- 17.7% Housing units vacant

- 0.1% Native, 38.3% White, 50.5 % Black, 4.3% Latinx , 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 4.4% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

Atlanta has experienced rapid economic and population growth over the last several decades. The city was formed in the tumultuous period of forced removal of Natives across the SE, including the Muscogee Creek and Cherokee peoples whose homelands the city occupies. An epicenter of the 20th century Civil Rights Movement, the city has become internationally recognized as a Black cultural hub. The only major Southeastern city emerging from the Civil war with its infrastructure intact, this crossroads city serves as a regional economic beacon.

However, growth has been highly unequal. Mirroring legacies of urban renewal, ambitious plans for urban expansion, redevelopment, and redesign, have not benefited many families, who instead face significant risks of housing displacement. Increasing climate hazards of floods, droughts, and heatwaves further threaten marginalized communities.

Green Infrastructure in Atlanta

GI planning in Atlanta encompasses stormwater management and planning for landscape connectivity in the context of large-scale urban development. Examples include the large number of regulatory plans implementing stormwater-focused GI in specific subbasins, the Atlanta Comprehensive and Resilience plans utilizing landscape and integrative concepts of GI, and the Atlanta Beltway plan which refers to GI but does not define it.

Plans utilizing landscape GI concepts focus on larger landscape elements (e.g. parks, the urban tree canopy, and trail networks) while stormwater-focused plans, including those using integrative concepts, focus more on hybrid facilities and green materials.

Functionally, plans use GI to manage urban hydrology, though some plans utilizing landscape concepts see it as a tool for supplying transportation and thermal regulation services.

Mirroring this functional focus, most benefits associated with GI relate to improved environmental conditions (largely water quality). However, stormwater-focused plans emphasize the reduced costs of infrastructure services, increasing property values, and a number of other economic and social benefits.

Key Findings

Atlanta has embraced an equity lens in its current Strategic GI Plan and Comprehensive Plan updates and has recognized the need to address gentrification within green urban redevelopment projects. However, mechanisms to do so remain under development. Opportunities exist to better integrate city-wide greening efforts, green stormwater infrastructure programs, and housing justice concerns.

18%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

45%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

18%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

9%

define equity

27%

explicitly refer to justice

45%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

18%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

27%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Atlanta through Maps

The City of Atlanta sits within a large metropolitan region characterized by a network of densely developed areas overlain by sharp lines of residential segregation. Stark differences in incomes, population density, vacancy rates, rent burden, and forest cover can be seen between the Southern and Eastern portions of the city as compared to the more densely populated Downtown and more affluent Northern Suburbs.

How does Atlanta account for Equity in GI Planning?

Overall, no Atlanta plans cover all 10 of our equity dimensions despite addressing at least some equity concerns. In a few key areas, they represent current best practices across our study cities, namely in understanding the contextual value of GI and the hazards that GI-related redevelopment poses.

There is a promising trend in the most current plans to center equity concerns. However, most plans don’t define equity or address justice. A major need exists for procedures to involve communities in the evaluation of existing planning efforts.

Envisioning Equity

No plans besides the GI Strategic Action Plan define equity. The most complete framings of equity are found in the Comp and Resilience plans, which include the idea of building intergenerational wealth as a way to move Atlanta out of the top 10 most income unequal cities. Mentions of justice are rare, and while acknowledging historical struggles, they largely do not acknowledge their continuation in the present or the capacity of city agencies and government to address them. Overall, framings revolve around using GI to provide universal benefits for all Atlantans.

Procedural Equity

With few exceptions, many of the mechanisms for community inclusion remain unspecified, and there are extremely limited avenues for affected communities to evaluate planned outcomes. For example, while Atlanta’s updated Comprehensive Plan sought community input, participation in design and implementation is largely limited to public agencies. While the Comp plan is the only plan that specifies mechanisms for community evaluation, means to do so remain limited, namely, a livability index and the Department of Parks and Recreation ongoing needs assessments. The Resilience strategy sought extensive public input through a number of avenues, representing one of the more inclusive planning processes we examined. However, the plan does not demonstrate how this engagement included all of Atlanta’s diverse communities.

Distributional Equity

All Atlanta plans use GI to reduce urban hazards and add value to the urban landscape. The dominant concerns around equity in the GI strategic plan revolve around historical and ongoing uneven distributions of flooding hazards and green redevelopment’s association with gentrification. Plans acknowledge the risks of gentrification associated with urban redevelopment projects catalyzed by large public investments in GI, in particular around parks. Both the Comp plan and GI Action Plan acknowledge the added need for labor to maintain GI, and many stormwater plans actively seek volunteer labor from communities where GI is implemented but do not discuss compensation. The resilience plan acknowledges the need for increasing access of marginalized communities to higher-value labor to build community wealth but does not specify any mechanisms to do so through GI.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Atlanta has numerous opportunities for improving equity in its GI planning and programs. As the city continues to grow in population and economic activity, a core issue is who benefits and who pays for ongoing redevelopment projects. Like many redeveloping cities, new forms of decision-making are likely required to guide investments in public services, infrastructure, and housing that benefit current residents without displacing them. Like many other cities we examined, Atlanta struggles with implementing creative drainage solutions to meet regulatory requirements while meeting other interdependent social, environmental, and infrastructural objectives in the context of extreme income and housing inequality. To that end, we provide concrete recommendations for communities, city policy makers, and non-government entities involved in Green Infrastructure in Atlanta.

Community Groups

Atlanta has numerous communities that have long fought for their right to thrive within the city, and unfortunately current plans only rarely discuss their ongoing struggles. Some headway has been made with community-based planning practices that sought to create binding visions for neighborhood planning and guiding city investments in public infrastructure, as evidenced within the Proctor Creek and Sugar and Intrenchment creek WIPS (which reference community-led visions from plans not authored by city agencies).

1. The Need for Substantive and Transparent Community Engagement

Current planning practices in Atlanta have almost no mechanisms for community-based evaluation of the implementation of GI plans aside from Parks and Recreation needs assessments. However, the current administration has centered equity concerns within the current GI plan, and this may present an opportunity for community groups to demand such mechanisms, alongside the creation of mechanisms for preventing housing displacement from urban redevelopment projects and GI programs.

2. Reclaiming the Value of GI = Reclaiming the Value Of Urban Land

Communities must continue to find alternative means of owning and valuing land outside of the speculative real estate market; in other cities, these have taken the forms of limited equity housing co-ops, and a national conversation around public banking and the right to housing. Such mechanisms may require a deep restructuring of city budgets and revenue generation mechanisms, as well as approaches to build community wealth that are not solely based on property value.

3. Building Community Cohesion Through Community Organizing

Strong internal community organizing forms the foundation of strong community-led planning. Community groups must continue to organize around their collective interest and should be supported by city agencies and NGOs. However, when partnering with NGOs, CDCs, and city agencies, strong community organizing will be required so external influences and funding do not cause or exacerbate divisions within the community.

Policy Makers and Planners

A diverse array of city agencies and government entities are involved in GI planning in Atlanta and the GI Strategic Plan has a welcome focus on equity issues. However, the Atlanta plans at large are contradictory about what GI is and what it does and contain limited processes for public engagement and participation from planning through evaluation.

1. Rooting GI in the urban landscape for community needs

Planners and policy makers should acknowledge that the GI concept must integrate a diverse array of private and public green spaces. While current plans focus on stormwater and flooding, other emergent approaches seek to create functional alternative transit networks, including pedestrian, bicycle, light electric vehicle, and environmentally friendly mass transit. These linkages should be more clearly identified and strengthened to provide a more sound social, environmental, and infrastructural basis for integrative planning efforts.

2. From Words to Action

Planners and policy makers need to move beyond discussing equity concerns in plans and move towards creating binding statutory and regulatory mechanisms for community inclusion in plan formulation and evaluation. These include specific mechanisms for community inclusion in shaping city policies prioritizing building property value over community incomes. Existing processes for community inclusion (as in the GI Strategic Plan and Resilience Plans) must become more transparent of what demographics in the city participated in plan creation.

3. Clarifying Definitions and Making them Count

One cannot plan for and cannot measure what one has not defined. Policy makers and planners must draw on strong public engagement mechanisms to articulate robust definitions of equity that can become encoded in city policies and plans.

Foundations and Funders

Foundations and funders in Atlanta have contributed to community-engaged planning processes dealing with Green Infrastructure. However, these plans are not binding upon city agencies. While policy makers and planners should build in such mechanisms, funders can support community organizing which forms the foundation of effective and just urban environmental governance.

1. Support Intersectional Organizing

Dedicated funding for community organizing around environmental, housing, and social justice needs to support existing community-led initiatives to address those intersectional challenges. Like many other cities, open forums to discuss and strategize around these intersecting issues are lacking. Creating new mechanisms to facilitate collaboration and joint planning between disparate groups is necessary.

2. From the Grassroots to City Hall

Community-based initiatives need to find concrete avenues for translating into binding mechanisms for city agencies when enacting and evaluating programs. Community-led plans without follow-through can undermine public appetite for engagement in future planning efforts, and yet, planning is required to address intersecting challenges around urban stormwater, flooding, and housing. So while many of the most disaffected communities may abandon planning processes, theirs are the voices most needed to formulate alternative visions and futures in city plans. Funders should prioritize efforts that support organizing on the frontlines of displacement and climate hazards and seek to create lasting structural and institutional change.

3. Rethinking and Remaking Urban Form

Foundations and funders should also collaborate with communities and city agencies for a larger scale rethink around the functions and benefits of GI. For example, it may be necessary to eliminate further development within flood-prone areas and build more affordable housing outside of hazard-prone areas rather than facilitating redevelopment with GI. Larger scale analyses of runoff, social and environmental inequality, and housing needs may yield insight into how other parts of the city can be redeveloped to improve economic and housing justice while making space for nature and improving climate resilience.

Closing Insights

Planning for equity in Green Infrastructure requires a deep rethinking and restructuring of urban governance to build wealth and value for communities while reshaping the city to be more socially just and environmentally resilient. GI, like other public realm investments, has long-term impacts on the quality of the built environment, and with appropriate social decision-making processes, can provide valuable public services for generations to come. Atlanta has opportunities to address its long-standing inequalities in wealth and exposure to environmental hazards, but these opportunities require changing the status quo around redevelopment.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.