MILWAUKEE

Incorporated 1846

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

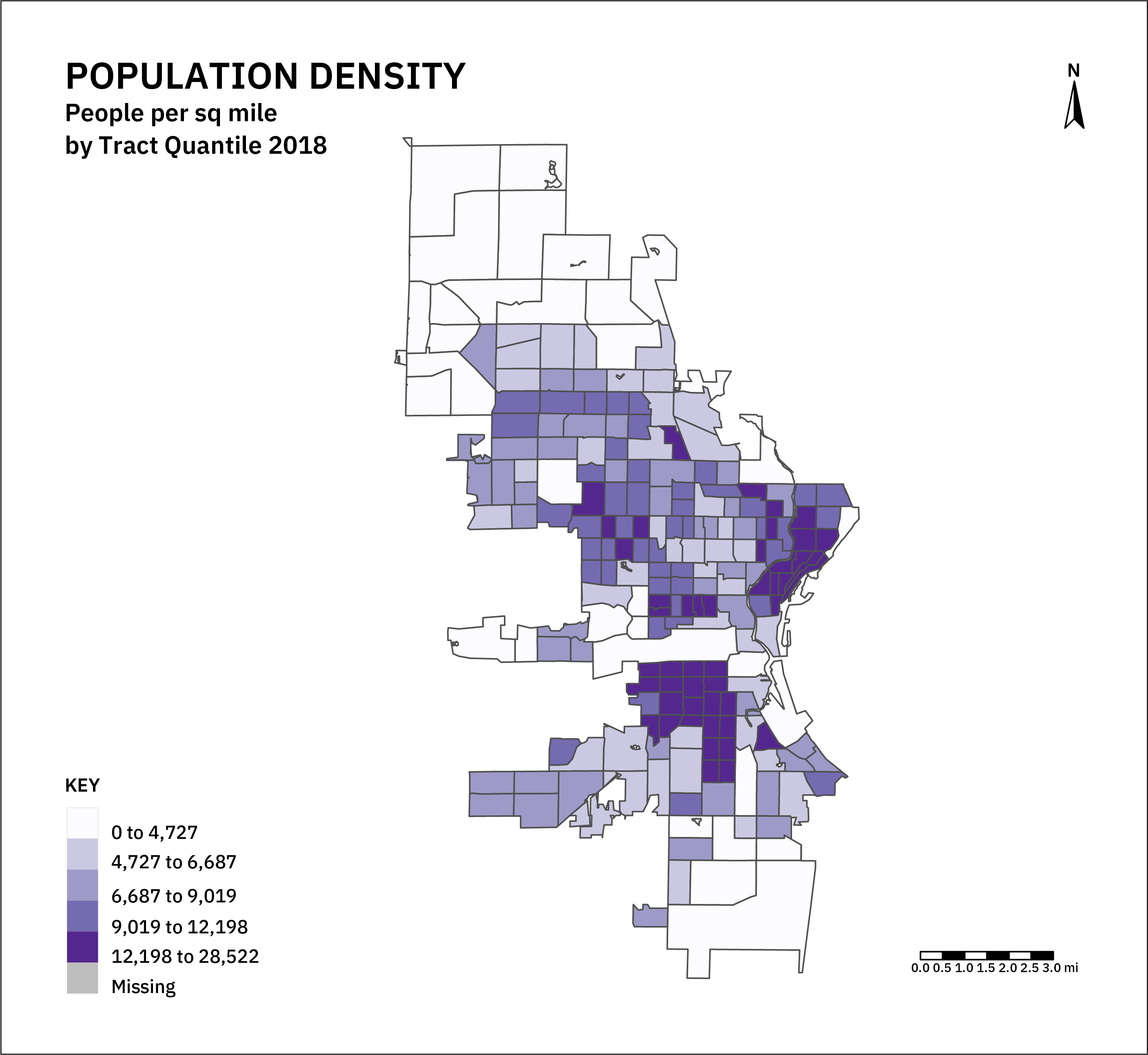

- 96.2 sq miles

- 596,886 Total Population

- 6,206 People per sq. mile

- 2% Forest cover

- Temperate Broadleaf and Mixed Forests Biome

- 9.5% Developed open space

- $40,036 Median household income

- 22.1% Live below federal poverty level

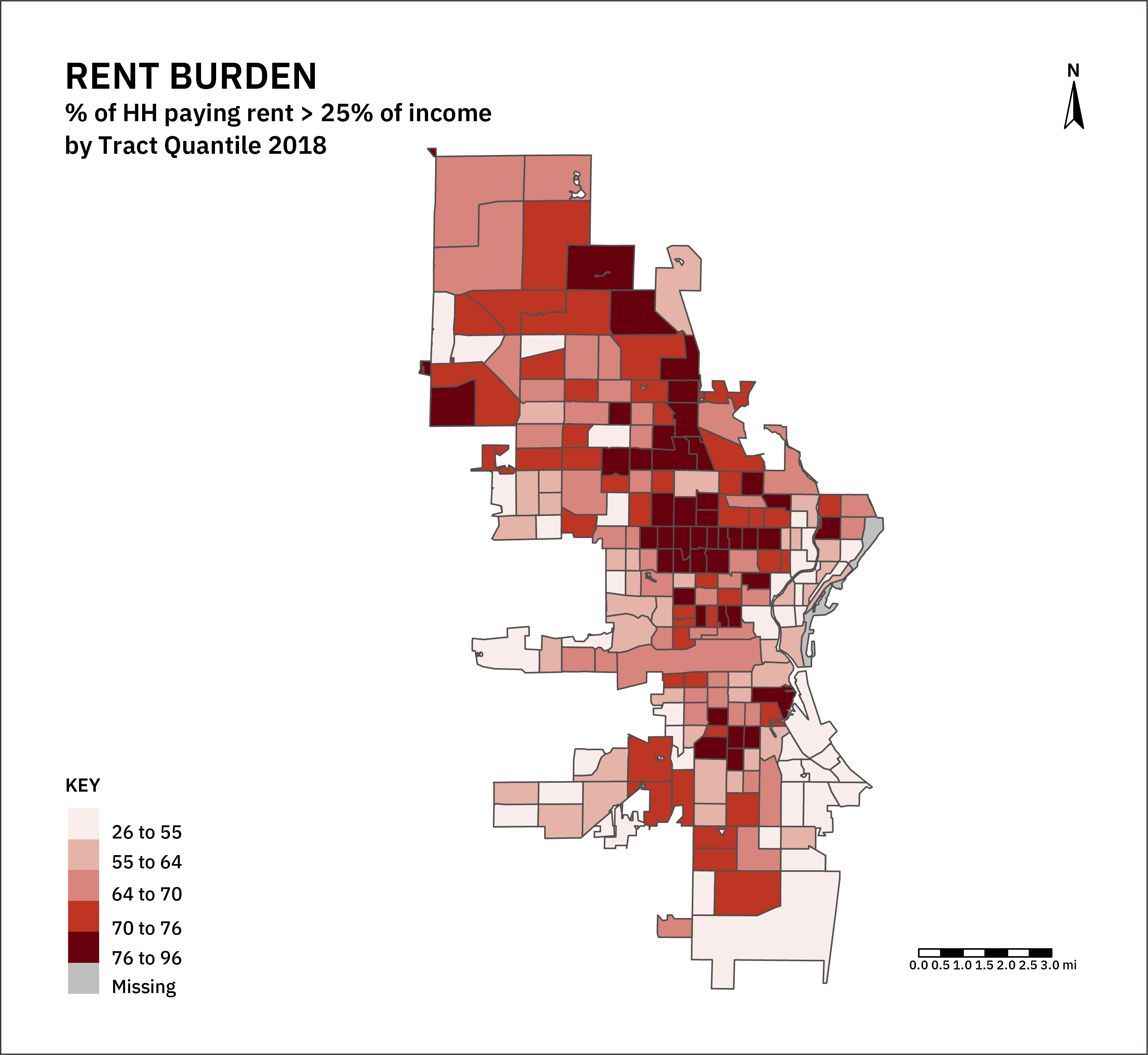

- 65.5% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 10.9% Housing units vacant

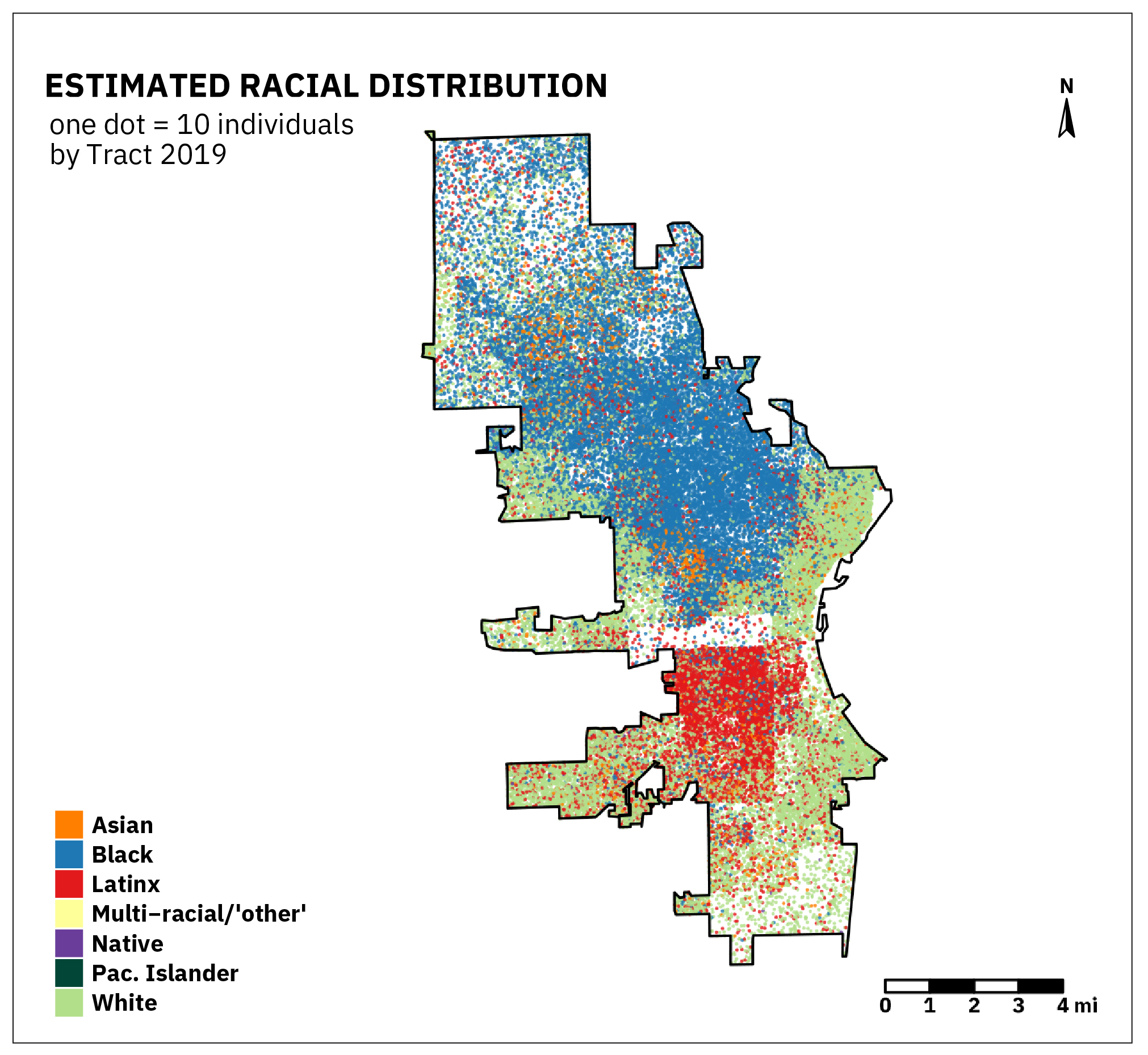

- 0.5% Native, 35.1% White, 38.3% Black, 19% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 4.2% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The area occupied by the City of Milwaukee has served as an important gathering place for several Native Nations, including Menomonee peoples, since time immemorial, and continues to be a center of Indigenous organizing. Since its colonization in the mid-19th century by European peoples, the city has developed as an agricultural export hub and industrial center. These industries attracted significant numbers of Black workers after the Civil War, and numerous immigrants contributed to population growth through the 20th century. Like other midwestern cities however, industrial decline and racist policies have made the Metropolitan region one of the most segregated in America.

Throughout its development, the city has made large investments in public works and infrastructure to improve conditions for urban residents. Like other former manufacturing centers, the city’s economy is now largely dominated by service industries and is experiencing uneven growth in property values. Climate change threatens the city with heatwaves and extreme precipitation events, exacerbating existing environmental justice issues. In the face of these challenges, numerous non-profits and city initiatives seek to accelerate a just transition.

Green Infrastructure in Milwaukee

The City of Milwaukee plans for Green Infrastructure through a dedicated GI Plan, a city-wide Green Streets Plan, a comprehensive Citywide Policy Plan, and its sustainability plan, ReFresh Milwaukee. The city has long been recognized as a leader in using Green Infrastructure for stormwater management in its separated sewer areas, and must plan alongside the Metropolitan Milwaukee Sewerage District overseeing the combined sewer system service much of the city (whose plans fall outside the scope of this analysis). More recently, its extensive green stormwater infrastructure programs have been combined with city-wide approaches for urban greening, building on twin legacies of sanitary infrastructure and parks planning.

Reflecting this broad and integrated approach, Milwaukee led among cities in terms of the diversity of elements considered as part of its green infrastructure system. While the city includes networks and corridors, it appears to omit trails from consideration.

Functionally, GI plans focus on regulating urban hydrology. GI functions also include filtering air and are unique among cities examined in defining health as a core function.

The benefits attributed to GI by Milwaukee GI plans are diverse, pertaining to numerous socio-economic, technological, and environmental benefits along with its contribution to overall urban resilience. Mirroring the omission of trails, recreation does not appear to be a focus of GI planning.

Key Findings

Milwaukee GI plans provide an example of how a city can create a GI-based economic sector that develops new forms of expertise and builds wealth in urban communities. Milwaukee GI plans refer to the need to consider equity, and in some cases justice, but do not define either term. Despite a proliferation of non-profit led initiatives for consultative planning, GI plans would benefit from elaboration of dedicated inclusive means for implementation and evaluation.

75%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

25%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

50%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

25%

explicitly refer to justice

75%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

25%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Milwaukee through Maps

Milwaukee is a diverse and yet highly segregated city, with uneven distributions of income, rent burden, and vacancy correlating with racial composition. The urban core, in particular, has never recovered from higher income, and predominantly White, families moving to the suburbs post-World War II. In contrast, the waterfront and southern portions of the city have attracted residents and businesses with significant reinvestment in existing and new development. Patterns of green space are unequal and appear to track income, with larger parks and green spaces in more affluent suburbs and the redeveloped waterfront.

How does Milwaukee account for Equity in GI Planning?

Despite a legacy of grappling with equity issues, Milwaukee GI plans do not define equity or justice.

Some plans include promising mechanisms for public engagement; and have some best practices for community engagement, however, there is room for improvement and consistency.

All of the Milwaukee plans that address GI seek to redistribute multiple hazards and improve multiple values of urban lands, but weakly consider context and existing disparities. Plans are also notable for their GI-related labor strategies.

Envisioning Equity

GI plans in Milwaukee focus on providing universal benefits to all city residents. The Refresh Milwaukee Sustainability Plan offers the most extensive discussion of equity issues, with a welcome focus on equitable wealth building through job creation. Despite an emphasis on honoring diverse experiences and perspectives, there is extremely limited discussion of historical and ongoing processes causing urban inequality.

The Sustainability Plan mentions environmental justice as a core goal, however, there is no discussion of specific redress or transformation of decision-making processes. The city-wide GI Plan and Comprehensive Plan rely on the same general framing as the Sustainability Plan but do not forcefully link the city’s extensive GI programs to specific equity concerns.

Procedural Equity

Milwaukee GI plans have some leading examples of community led GI implementation, notably in its Walnut Way city supported programs. These innovative approaches for including communities in the early stages of planning and project design fall short in meaningfully involving communities throughout the GI lifecycle, which plagues many non-profit-led initiatives. Like other Sustainability plans, the Refresh Plan has best practices in surveying public opinion. This process is led by an appointed leadership board that has broad engagement with city agencies, civil society, and the business community. However, it is unclear how well the respondents represent the city’s population and further, whether historically disenfranchised and marginalized communities have a voice in the process, despite extensive outreach efforts.

Another bright spot is in the design process outlined in the city-wide GI plan, which seeks to build community capacity through job training, along with technical and financial assistance. In short, the plan attempts to build design expertise into the communities targeted for GI projects. Specific methods to implement this collaborative design process are unclear. In the broader scope of GI planning, the lack of substance and clarity in the plan raises the possibility of failing to meaningfully engage communities throughout planning stages, despite intentions to do so. While there are mechanisms in place to track complaints, there are no discernible procedures to respond to the input and to change course in the event of unforeseen problems or issues. The Sustainability Plan relies upon volunteers to evaluate whether the Plan is meeting its self-defined targets. The Green Streets Stormwater Plan also has some evaluative components, but they are limited to internal city agency processes.

Distributional Equity

Milwaukee GI plans are exceptional in addressing labor issues by explicitly seeking to build a highly skilled GI labor force that benefits marginalized communities. They do so through commitments in the city-wide policy plan and GI plan to build a diverse GI labor force in several related economic sectors. This strategy seeks to serve as a model for other cities, aims to have members of marginalized groups become GI experts and professionals, and generate economic value both within city work and by consulting and advising on programs across the world.

Otherwise, the distributional impacts of GI are unremarkable. All GI plans focus on a range of hazards but do not discuss differential, uneven, or contextual vulnerability or how GI may shift risks of different types, although the city and local nonprofits are actively studying these issues. Value-wise, plans are similar to other cities in that they extol the virtues of GI’s multiple benefits but only weakly address how benefits, risks, and potential unintended consequences associated with city-led GI may vary across communities.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Like other cities, Milwaukee has embraced official equity planning and created an Office of Equity and Inclusion since the beginning of this project. However, as of the writing of this analysis, neither of these initiatives address the city's green infrastructure programs. Milwaukee has a long history of urban ecological education, outreach, and research, focusing on reconnecting urban communities with their resident ecosystems, which is reflected in its focus on creating a citywide green infrastructure system. Given the inconsistency in addressing equity issues in the city's current GI plans, we offer several recommendations to stakeholder groups that are working on GI and equity issues across the city.

Community Groups

Residents and communities in Milwaukee have long been working on environmental and social justice issues. The city has one of the oldest chapters of the NAACP and has long been an area of intensive organizing and struggle around racial justice issues. Community groups appear focused on attracting investment into neglected neighborhoods. This work has been supported by reclaiming narratives of what makes spaces valuable undertaken by the Milwaukee Environmental Justice Lab. Despite city and community-led initiatives, the Building Movement Project’s Race to Lead series found significant gaps in the racial equity of nonprofit sector leadership in the City. These tensions highlight several issues at the intersection of urban greening, governance, and community organizing that align with our findings of inconsistent community inclusion in GI planning. Flagship projects, such as the Walnut Way initiative, offer scalable models within the city. To expand upon these initiatives,. we offer two recommendations to improve the equity of community-oriented green infrastructure.

- Intersectional Urban Greening

Current planning practices in Milwaukee have almost no mechanisms for community-based evaluation of GI plan implementation. This is surprising, given that the city is implementing an integrative concept of GI in the public realm and for stormwater system improvements. However, some plan updates promise the creation of community forums for evaluation. Given the broader trend towards inclusive planning, including the use of an equity lens and planning-focused city ordinances, there are opportunities to build transparent and binding mechanisms. Community groups can demand a greater voice in the evaluation of city programs and policies, building off of the inclusive approaches of the Sustainability Plan and the design charrette framework of the city-wide GI Plan. Greater community inclusion in GI planning can and should address the multifaceted concerns of marginalized groups. A primary way of changing the conversation in the next wave of GI planning is to center the existing work of concerned grassroots organizations to formally define the concepts of equity and justice. Further, those concepts must underpin community leadership of planning alongside well-developed frameworks that address distributional inequity.

2. Reclaiming Value and Mitigating Hazards

Milwaukee has high rates of housing vacancy and rent burden in marginalized neighborhoods. This market failure of providing affordable housing is a direct product of waves of racialized disinvestment in the city that continue to this day. Systemic GI investments can certainly raise property values, but not necessarily to the benefit of renters or property owners with limited incomes. Simply attracting external investment to these neighborhoods may cause similar gentrification issues to those observed in other cities, as largely speculative market mechanisms require profit returns to provide incentives for additional property investment. Milwaukee has a complex history of urban renewal that was both highly destructive and gave rise to a resurgent Black middle class. Prior efforts to attract external investment have led to significant displacement from some neighborhoods, albeit at a rate slightly lower than other US cities. While the city has an anti-displacement plan, that plan does not mention GI investments. There is a need to examine the relationship between public realm investments such as GI and the waves of displacement already occurring to not replicate these problems as GI programs expand. The same can be said for using GI to mitigate stormwater flooding in the city. Existing programs like the Water Centric City concept and its approach to skills and jobs development can be expanded to address structural economic justice in neighborhoods targeted for GI investments.

Policy Makers & Planners

Currently, Milwaukee policy makers and planners are grappling with equity and displacement issues but not actively in GI plans. This gap needs to be addressed because for urban dwellers GI is a key component of their quality of life. GI impacts infrastructure performance, property value, and many residential services. Additionally, since Milwaukee County is a member of the Government Alliance on Race and Equity, there is a structure in place to address regional equity issues. To improve the equity of GI planning in the city of Milwaukee, policy makers and planners should consider the following gaps identified in current plans.

- Specifying Equity in Relation to GI

No GI plan examined in Milwaukee defined equity or justice. This is a major omission for a city that is a green infrastructure leader, has other active equity initiatives in place, and suffers from a high degree of segregation. While the Water Centric City concept and steps already taken to ensure community engagement in GI projects are admirable, these need to be supported by a broader understanding of the relationship between green infrastructure and racial justice. These definitions should come from the rich ecosystem of community organizations working on racial justice in the city as well as everyday residents grappling with neighborhood change and environmental issues.

2. More Inclusive and Equitable Planning

Milwaukee GI plans fall short in building meaningful community engagement throughout the planning lifecycle. There is a need to build in more consistency for communities to lead planning efforts that impact their lives. Such an approach, required in many of our study cities, relies on meeting communities where they are, including providing compensation and services that enable community participation and creating meaningful mechanisms for concerns that can be met through planning, legislation, and the modification of city programs.

Foundations and Funders

Multiple organizations have funded green infrastructure-related activity in Milwaukee. More work is needed to determine the impact and efficacy of current efforts to improve the equity of GI, especially since current GI plans do not have an equity focus. Existing efforts could be expanded in several concrete ways.

- Supporting Intersectional Organizing

As in other cities, significant community organizing energies are focused on anti-displacement strategies and economic and racial justice issues. With the large GI investments from city and metropolitan agencies, GI programs can be structured to address these interwoven concerns. However, this will require dedicated support for existing community movements.

Closing Insights

Milwaukee has been recognized as a leader in GI implementation and has adopted a city-wide integrated approach to develop and plan for a diverse GI system. However, despite a strong focus on labor sector development with the Water Centric City concept, inclusive design practices, and a collaboratively framed Sustainability Plan, equity and justice remain largely unaddressed by Milwaukee GI plans. The question remains how one of the more segregated cities in America will address its housing and racial justice crises through its extensive GI programs.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.