What We Did

Step 01

20 US Cities Selected

Step 02

122 City Plans Analyzed

Step 03

Green Infrastructure (GI)

Step 04

Equity

Step 05

Assess Overall Equity of GI in Plans

Our project, “Is Green Infrastructure a Universal Good?” is motivated by numerous observations that city investments in green infrastructure in the U.S. have not benefited all urban residents equally, and may worsen existing environmental and social injustices. Our initial research was guided by three questions.

- To what degree do urban plans acknowledge that underserved neighborhoods may have different perceptions, needs, and support for green infrastructure projects?

- Do municipal plans discuss different experiences and perceptions of green infrastructure by diverse communities?

- Do the burdens of GI fall inequitably upon marginalized communities?

For our analysis, we chose 20 different-sized US cities including many recognized as leaders in Green Infrastructure (GI). Our early efforts found that cities plan for GI in diverse types of plans, requiring that we expand our analysis to all city plans addressing ‘green infrastructure.’ Across the 20 cities we examined, we found 122 city plans using the term ‘green infrastructure.’ Using content analysis methods, we identified how plans conceive of GI, its social impacts, and its relationship with equity and justice. We also evaluated the equity of the GI planning process.

To assess the equity of GI planning, we first had to understand how planners in each city defined GI. This included what was considered part of the city’s GI system, along with its functions and benefits.

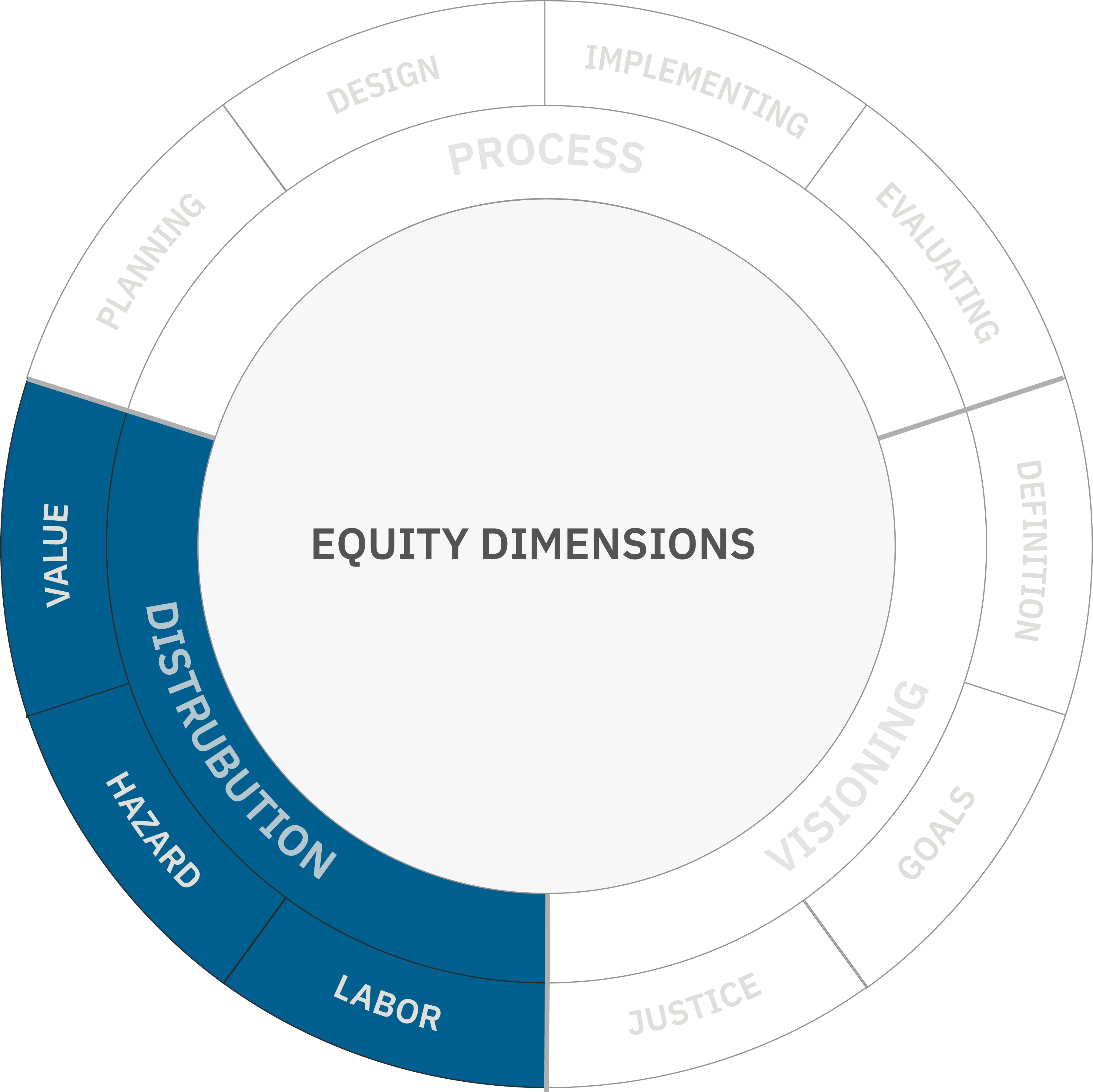

We then examined how plans conceived of and addressed equity within city GI plans in three dimensions:

- Conceptual: if and how equity is envisioned, including how it is defined and framed, and if it addressed issues of justice,

- Procedural: how impacted communities were involved in the planning, designing, implementation, and evaluation of GI, and

- Distributional: how proposed uses of GI affect current distributions of hazards, value, and labor.

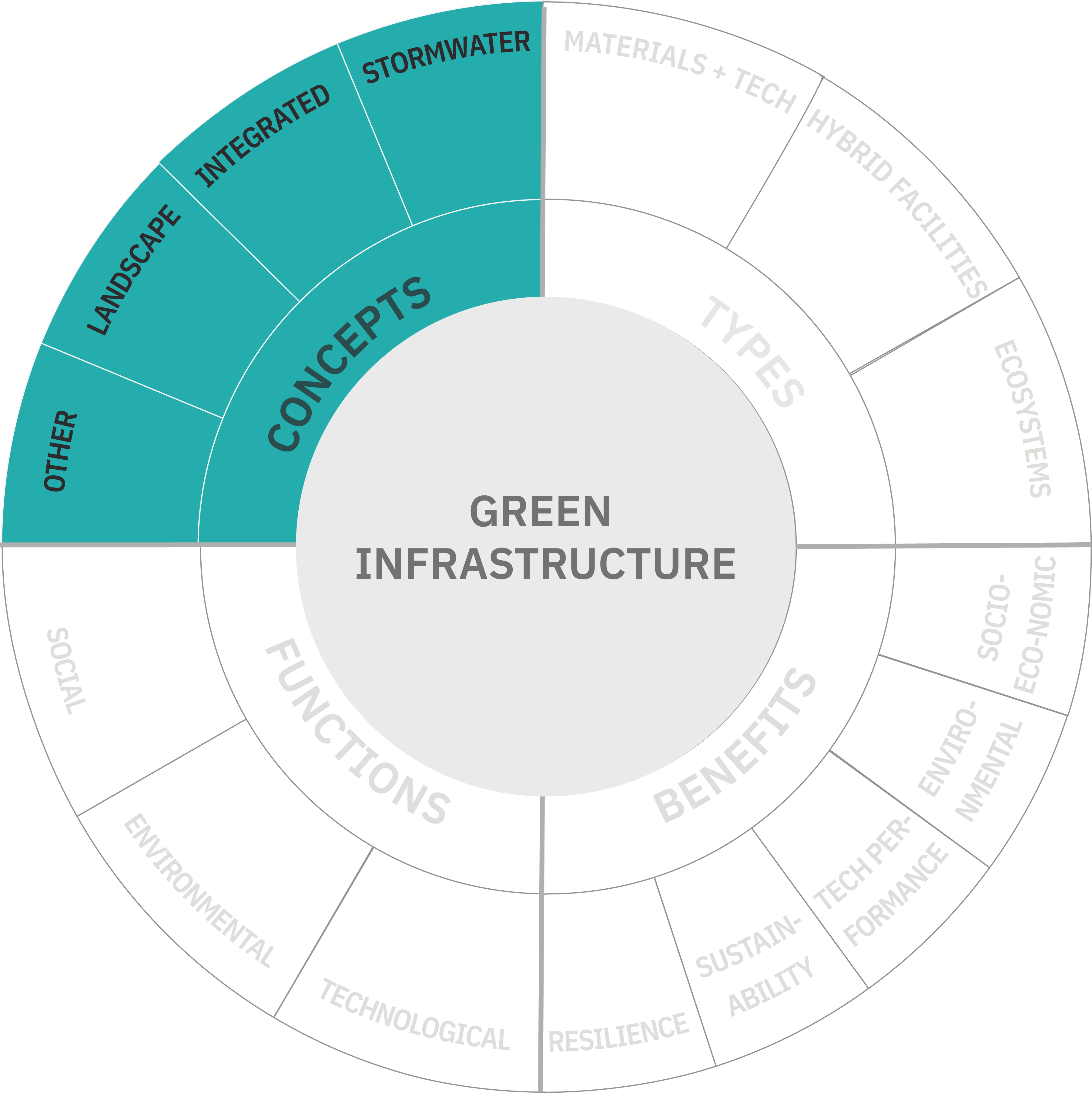

Defining Green Infrastructure

Green Infrastructure (GI) refers to a system of interconnected ecosystems, ecological-technological hybrids, and built infrastructures providing contextual social, environmental, and technological functions and benefits. As a planning concept, GI brings attention to how urban ecosystems and built infrastructures function in relation to each other to achieve socially negotiated goals. In other words, Green Infrastructure combines elements of the natural environment and engineered systems, to provide a variety of services of value to communities. Identifying how GI was defined in plans allowed us to assess the 'state' of GI thinking in city planning.

Concepts

Green Infrastructure as a concept has evolved substantially from its earliest uses in the mid-1990s, and today takes three distinct forms.

1. Landscape: Early GI planning focused on connecting diverse green elements across landscapes to provide multiple functions and benefits for humans while conserving ecological systems. These efforts were aligned with urban planning traditions, creating integrated parkways, park systems, and green public realms in cities, often referred to as the ‘green armature’ of the city.

2. Stormwater: In 2007, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) adopted the term as a cost-effective strategy for managing urban stormwater to meet Clean Water Act (CWA) requirements. Many cities, facing significant financial hurdles to updating old storm and sanitary sewer systems, seized the opportunity. This ‘stormwater’ focused concept aligns with existing efforts to improve urban drainage systems like Low-Impact Development practices, Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems, and Stormwater Best Management Practices.

3. Integration: Over time, some cities have integrated the two concepts. Integration has been difficult, partly due to confusion around what GI is and does, much of it stemming from the regulatory requirements and limitations of EPA’s jurisdiction under the CWA. Despite these challenges, some cities use GI planning to improve ecological integrity and stormwater management. Under this umbrella, many cities are also thinking expansively about ‘greening’ grey infrastructure systems, such as energy, transportation, waste handling, and manufacturing.

Types of GI

'Types of Green Infrastructure' refers to the elements considered part of Green Infrastructure. We identified over 28 distinct types of GI from definitions in analyzed plans. We organized these into three major categories: ecological (vegetation, plants, soils, riparian zones, parks), ‘green’ materials (rain barrels, permeable pavers), and hybrid facilities (bioswales and green roofs).

Different types of GI require specific forms of planning and management to achieve their desired functions and benefits. Furthermore, the functions and benefits of GI depend on the type of GI, the relationship between GI types, social, ecological, and technological contexts, and relationships with other urban systems.

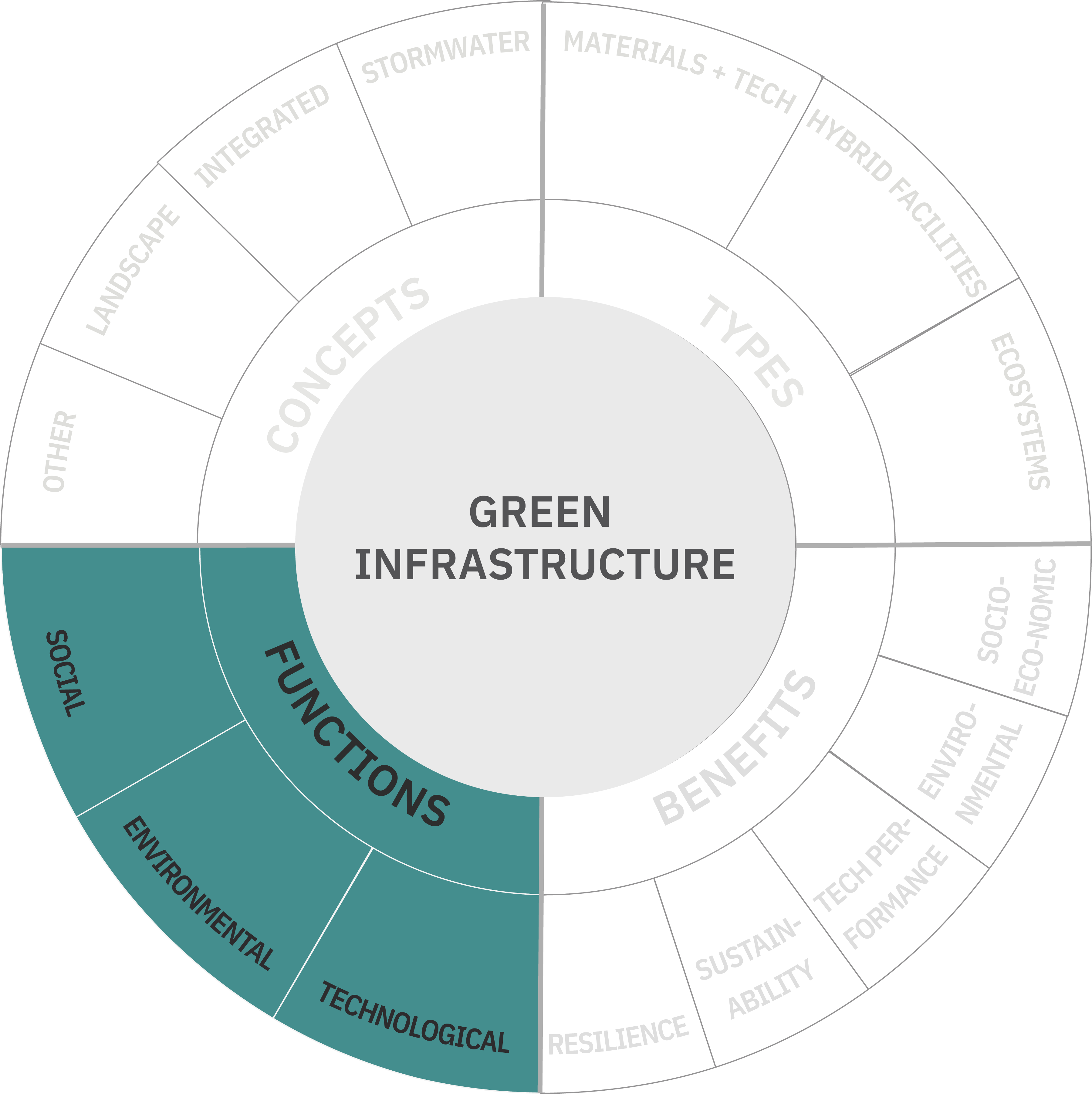

Functions

GI is often referred to as multifunctional. We examined how GI definitions within plans explained functions in terms of what GI is ‘assumed to do’. We identified 31 distinct functions of GI, which we organized into three categories:

- Technological (e.g. increasing efficiency of wastewater treatment facilities or providing a transportation link),

- Environmental (e.g. filtering air or water, providing habitat, reducing the urban heat island), and

- Social (e.g. providing spaces to gather and recreate).

The functions of GI also depend upon their relationship with built infrastructures, such as contaminants that threaten plant (and human) health, air pollution that degrades building materials, and the need for management to keep bioswales free of litter.

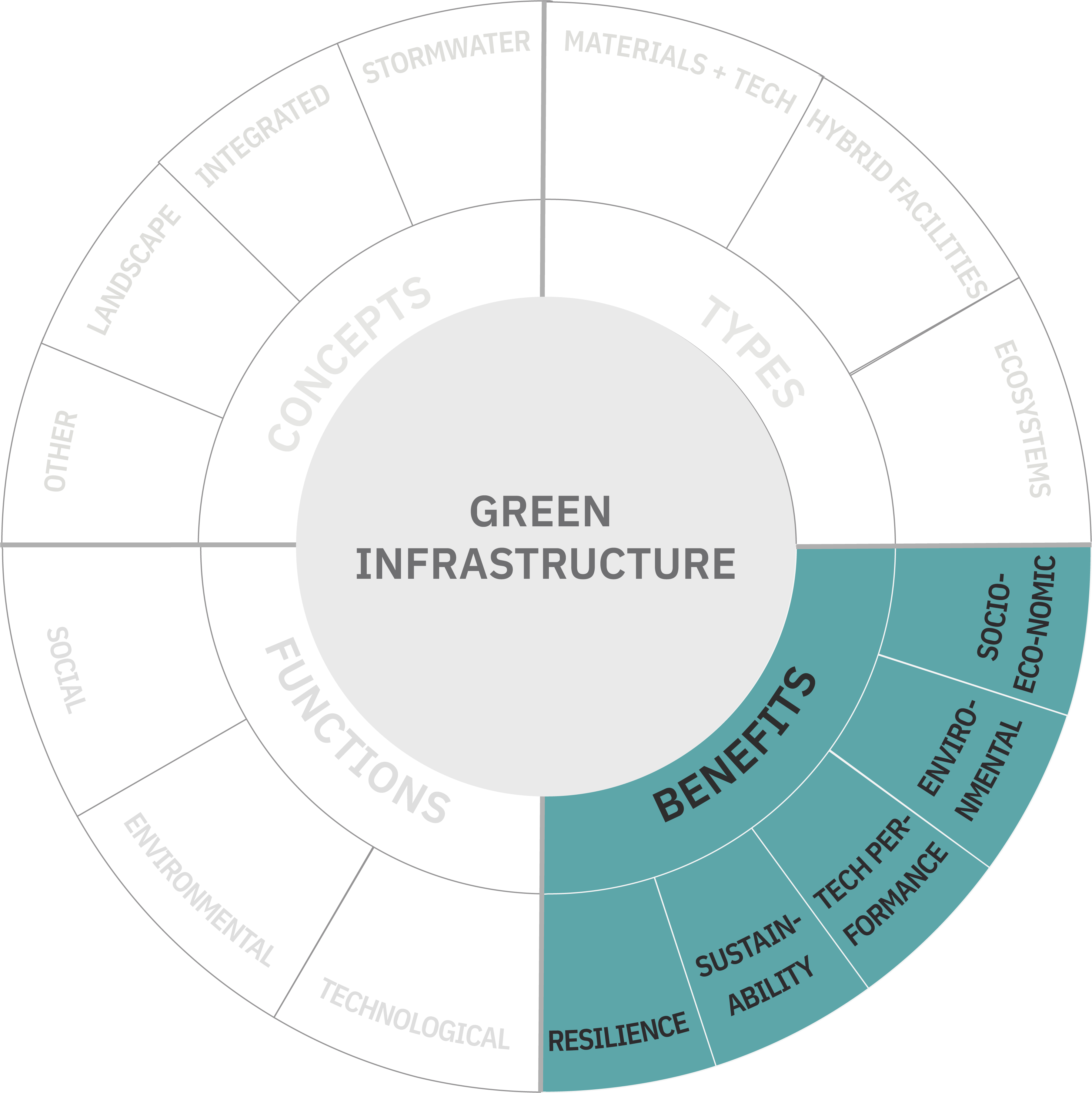

Benefits

The benefits of GI are closely related to its functions, yet refer to broader impacts of GI. Depending on the context, designed functions may or may not deliver intended benefits and may or may not deliver them equitably.

Context poses a major challenge in understanding the benefits of GI. Specific types of GI will have different benefits depending both on their relationships to other parts of GI networks and the built environment, as well as the ways they are perceived and experienced.

Within plans, over 62 distinct types of benefits attributed to GI were identified. These were thematically grouped into five categories:

- Socioeconomic ( improving health outcomes, reducing costs, increasing property value),

- Environmental (enriching biodiversity, improving air and water quality),

- Technological (reducing energy costs, increasing the lifespan of infrastructure systems), and

- Improving general resilience and sustainability.

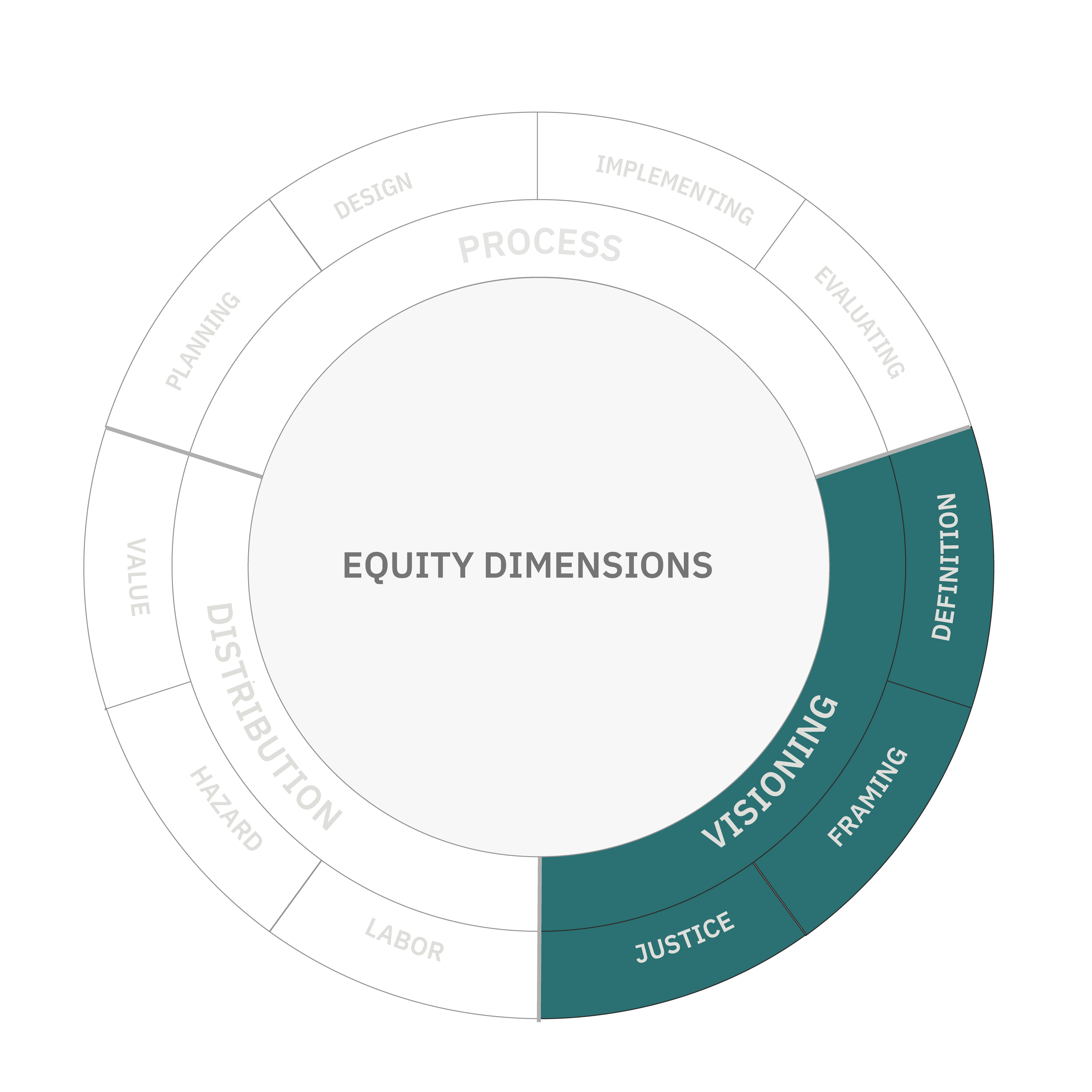

Defining Equity

Equity generally refers to fairness in process and outcomes, including the provision of resources based on need. We evaluate equity on this basis, although the term remains contested. Our guiding principles include the declaration of universal human rights, which includes the right to land, housing, livelihood, and a safe environment, along with the inherent right of political, economic, and cultural self-determination of oppressed and marginalized communities within the political systems that govern them. In planning practice, this right to self determination can take the form through the principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, but this principle must be based on substantive control over the planning process by all communities which will be impacted in order to achieve consensus based consent.

We refined these big ideas to create an evaluation tool to assess the equity of city plans in three major dimensions: conceptual, procedural, and distributional. A general method was used to examine each of these dimensions within urban GI plans, and to compare the equity of planning within and across cities. In plans that were examined, our evaluation framework scored 10 different categories on a scale of 0 (absent) to 4 (ideal) within each dimension. Below, we expand on the definitions of dimension and category, along with an evaluation system.

Envisioning Equity

Envisioning equity in GI plans refers to the way that equity is defined and framed in connection to GI. Of particular interest is the relationship between GI and environmental and social justice, including restorative and transformative justice.

Definitions: Where found, definitions were examined in terms of how they addressed equity’s conceptual, procedural, and distributional dimensions. We also looked for acknowledgement of the need to address equity in a city’s specific historical and present contexts, and if equity was defined by marginalized communities themselves.

Category

How equity is defined (Brand 2015)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Universal, general, or partial 'flat' definitions

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Addresses inequitable outcomes but not causes

Level 3: Functional

Articulated as core principle, addresses legacies, outcomes, and process

Level 4:

Ideal

All domains covered and specified within city context

Framing: When plans do not explicitly refer to the term equity, they may implicitly frame social concerns of GI. The concept of framing is used to examine if, and how, plans account for the explicit and implicit social interests around GI. Examples include disparities in access to opportunities, and the enjoyment of their related health and income benefits, based on racial, socioeconomic, and/or other social characteristics. Framing statements are often found in the goals of plans, background narratives, and in their vision statements.

Category

How equity is more broadly framed and discussed (Brownhill and Inch 2019)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Focuses on improving outcomes but not underlying conditions

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Described as core principle with limited substance or application

Level 3: Functional

Articulated as core principle, addresses legacies, outcomes, and process

Level 4:

Ideal

Truly visionary in terms of social transformations required to achieve equity and justice in city

Justice: Injustices are defined as the purposeful mistreatment of individuals or groups, often due to their perceived characteristics (such as race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and political ideologies), and/or relationships with land (e.g. forced removal and genocide of Native peoples). Cities are rife with past and current injustices. We examined plans for explicit references to justice in any sense including:

- Recognitional justice: the recognition of past and present injustices,

- Restorative justice: the description of specific steps to make reparations for those injustices, and

- Transformational justice: the inclusion of commitments to transform the systems that perpetuate harm.

Category

How plan addresses ongoing and historical injustice (Fraser 2009; Pellow 2017; Gilio-Whitaker 2019)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Justice as keyword with no content

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Some discussion of how historical and current injustices influence current conditions

Level 3: Functional

(In)justice defined by oppressed communities, includes recognition, restoration, and transformation

Level 4:

Ideal

Commitments of resources to be used in community led deliberative processes for reparations as defined by injured communities

Procedural Equity

Process or procedural equity often refers to the development of rules in society and their fair application. In GI planning, process equity looks at who is involved, and how, from creating plans to evaluating their implementation and impacts.

Planning: Procedural equity is determined by identifying which actors produce the plan and how this is accomplished. Equity is achieved when genuinely participatory and democratic planning methods are used and where affected communities and individuals have substantive input and control throughout the process. At a minimum, those involved in the planning process should be representative of those affected by planning outcomes.

Category

How those affected are involved in the planning process (Hopkins 2010)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Superficial engagement

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Formulaic engagement, obscured/manufactured consent

Level 3: Functional

Numerous avenues for input, transparent documentation, demonstrated inclusion

Level 4:

Ideal

Deliberative and pluralistic democratic process

Design: Plans do not often specify designs for GI facilities, however, they can specify the process and means of designing projects and policies. Equity in design requires the inclusion of parties affected by the design in the design process.

Category

How affected communities have input and control over design of GI (Nesbitt et al. 2018)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Superficial / post design consultation

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Formulaic / bounded engagement e.g. menu

Level 3: Functional

Co-produced designs

Level 4:

Ideal

Design in service of community needs

Implementation: Project implementation may fall outside of a plan’s scope. Still, plans can identify mechanisms for bringing GI from the drawing board into the real world, including tools for community involvement.

Category

How those affected are involved during implementation of GI programs (Quick and Feldman 2011)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Basic notification

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Limited coordination

Level 3: Functional

Substantive mechanisms with documentation of addressing concerns

Level 4:

Ideal

Implementation shaped by community needs

Evaluation: We cannot know how equitable GI is without robust evaluations of its overall impacts. In order to be equitable, these assessments should come from impacted communities themselves, be transparent, and be used to update planned initiatives.

Category

How those affected evaluate the impacts of GI (Oliveira and Pinho 2010)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Documentation of complaints

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Commitment to periodic check ins

Level 3: Functional

Concrete avenues for adaptive management of planned activities

Level 4:

Ideal

Mechanisms allowing for transformation of decision making procedures

Distributional Equity

The distributional equity of GI refers to the overall spatial and social allocation of services provided, the hazards it seeks to address (including unintended consequences), and the administration of labor required for implementation and maintenance. We focus on how GI plans understand and communicate about the distributional aspects of equity. Fully evaluating the distributional impacts of GI programs, projects, and policies described in plans is an area of ongoing analysis.

Value: Value broadly refers to how the ‘goods’ or benefits of GI are planned to be distributed spatially and among different social groups.

Category

Use of GI to influence value of urban space for affected individuals and communities (Nesbitt et al. 2018)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Intention to use GI to add value to urban landscape

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Some acknowledgement of disparities in perceived value of urban landscape, value framed using limited means

Level 3: Functional

Acknowledging differential perception and need of value of GI

Level 4:

Ideal

Plural framing of needed values of GI and relationship to other social objectives and systems of managing public infrastructures and urban lands

Hazard: GI often manages specific hazards as part of its core functions, such as reducing flooding, managing heat, or improving water quality. Evaluating the equity of GI hazard management involves examining the existing social and spatial distributions of hazards, how those distributions will be changed by the plan, whether some groups may be made more vulnerable, and if potential unintended consequences are addressed.

Category

Use of GI to influence social and spatial distributions of hazards (Nesbitt et al. 2018)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Intention to use GI to mitigate hazards

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Formulaic and context independent methods of estimating hazard reduction

Level 3: Functional

Analysis of causality of uneven hazards and vulnerability

Level 4:

Ideal

Pluralistic elucidation of hazard distribution, causality, and systemic impacts of GI

Labor: While a number of GI types may be self-organizing and maintaining, most require some form of labor throughout their life cycle. Labor equity refers to whose labor is required to create and maintain GI systems and how they are compensated.

Category

Acknowledgement of labor required for realization of GI, inclusive of planning, design, construction, maintenance. (e.g. Finewood et al. 2019, Gulsrud et al. 2018)

Level 0: Absent

Not present

Level 1:

Not Satisfactory

Acknowledgement of labor needs but no discussion of equity

Level 2: Nascent or Problematic

Acknowledgement of labor required throughout GI lifecycle but clear inequities present

Level 3: Functional

Specified pathways and mechanisms to distribute lifecycle labor benefits and address labor burdens

Level 4:

Ideal

Understanding of intersectional labor issues throughout GI lifecycle and relationship to structural inequality

Wrap Up/Summary

Our analysis and plan equity evaluation tool serve as resources for individuals, agencies, and communities to address gaps in the equitable governance of GI through the transformation of planning processes. Equity in GI planning is complex, multidimensional, and ultimately requires transforming urban governance.

Resources

City Plans

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Other Project Outputs

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study