DETROIT

Incorporated 1701

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

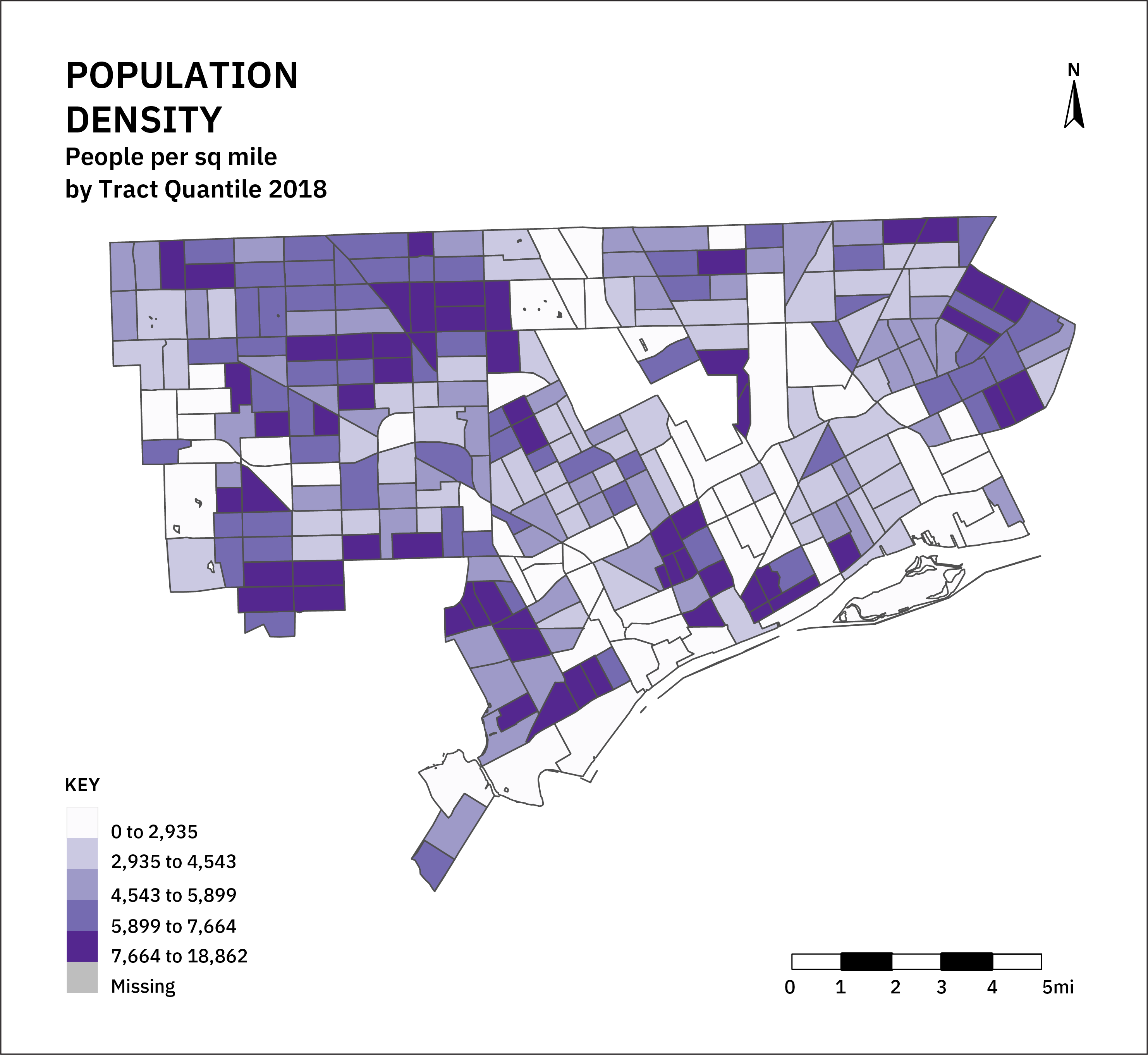

- 142.9 sq. miles

- 677,155 Total population

- 4,881 People per sq. mile

- 0.6% Forest cover

- Temperate Broadleaf and Mixed Forests Biome

- 5.4% Developed open space

- $29,481 Median household income

- 31.3% Live below the federal poverty level

- 72.4% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 28.5% Housing units vacant

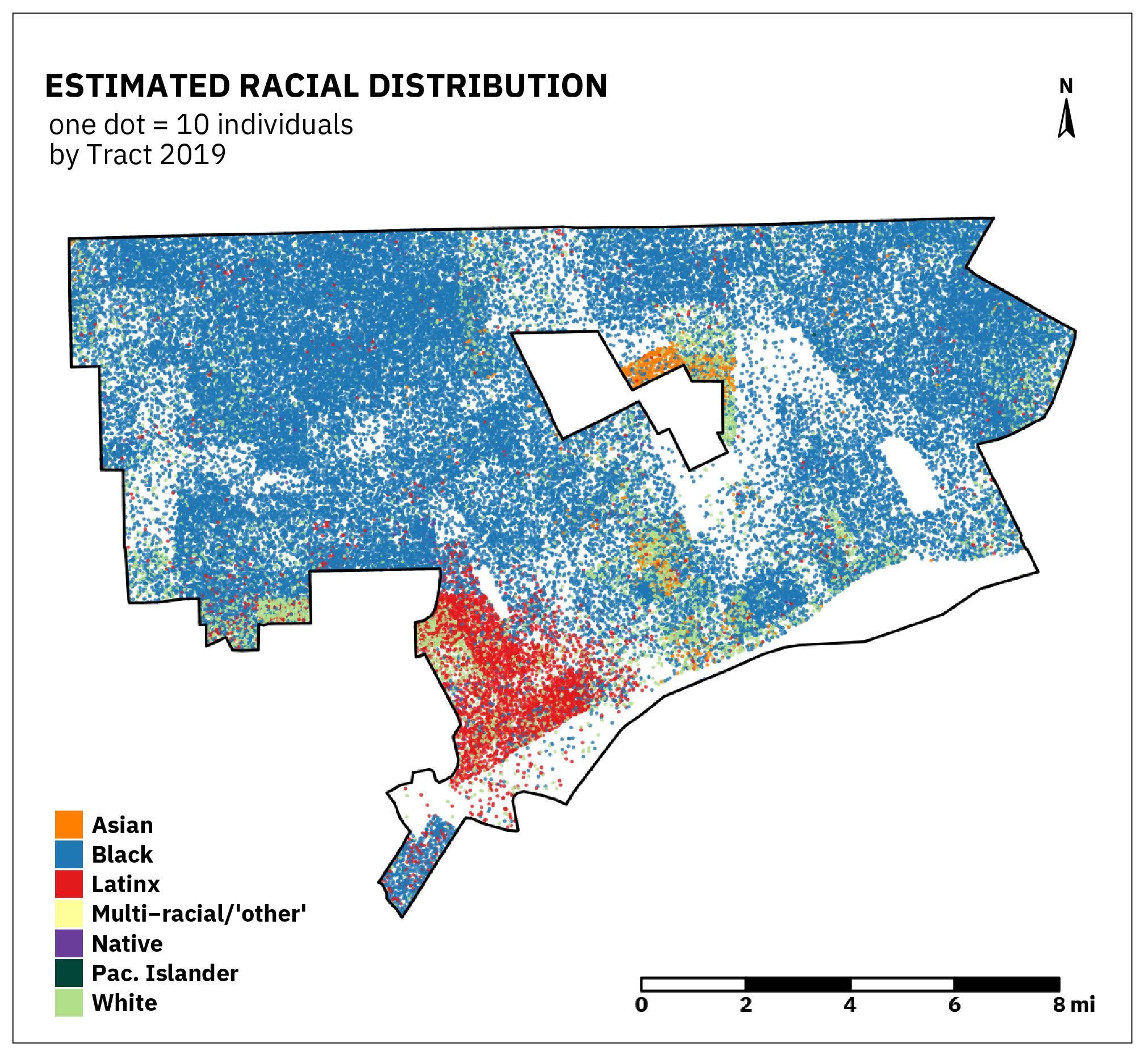

- 0.3% Native, 10.5% White, 78% Black, 7.7% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 1.7% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The City of Detroit occupies the homelands of Anishinaabeg peoples and continues to serve as a hub of Native culture and organizing. The city continues to be impacted by institutionalized forms of racism and high degrees of segregation and has long served as an epicenter of conversations, movements, and organizing for Indigenous, racial, labor, and environmental justice. Detroit communities continue to create flourishing forms of community-based green infrastructure including vacant lot reclamation and urban agriculture projects under broader goals of transformative justice.

City government, however, faces profound challenges from the ongoing impacts of racism, globalization, and disinvestment. Budget shortfalls have continued to increase infrastructure cost burdens on marginalized communities. Nearly one out of three households live below the federal poverty line, and the bankrupt city has faced major challenges in maintaining infrastructure, even as the metropolitan area has continued to grow. Climate change further threatens aging infrastructure systems, with increasing heavy rainfall, flooding, and heatwaves intersecting with the city’s existing environmental justice problems.

Green Infrastructure in Detroit

City-led GI plans in Detroit focus on stormwater management exclusively. The city will invest over $50 million in GI over the next decade to solve long-standing issues with surface water quality caused by storm runoff and combined sewer overflows. City-led plans also seek to improve socio-economic conditions with green stormwater infrastructure investments. In addition to extensive stormwater-focused programs, there is some integration of community initiatives to reclaim vacant lots and homes in broader efforts of greening and community revitalization.

Within city-led stormwater and sewer management plans GI is not defined with precision. The exception is the definition offered in the Upper Rouge GI Plan. However, this definition is somewhat narrow and only mentions trees, bioretention processes, and other stormwater management features, and does not encompass the broad range of community-led GI initiatives. Further, aside from a few narrow stormwater goals, city plans are unclear in how they define the desired goals and functions of these hybrid facilities and ecosystem elements.

Importantly, plans do not seem to analyze the potential social benefits or overall impacts of GI, even though the Upper Rouge Tunnel GI Plan states that part of the rationale for examining GI as a stormwater management strategy was its broader social value. While some community-engaged initiatives, like the Detroit Future City program and the Water Agenda, have broader concepts of GI and equity at play, they do not appear to be binding on city agencies, and so fall outside the scope of this analysis.

Key Findings

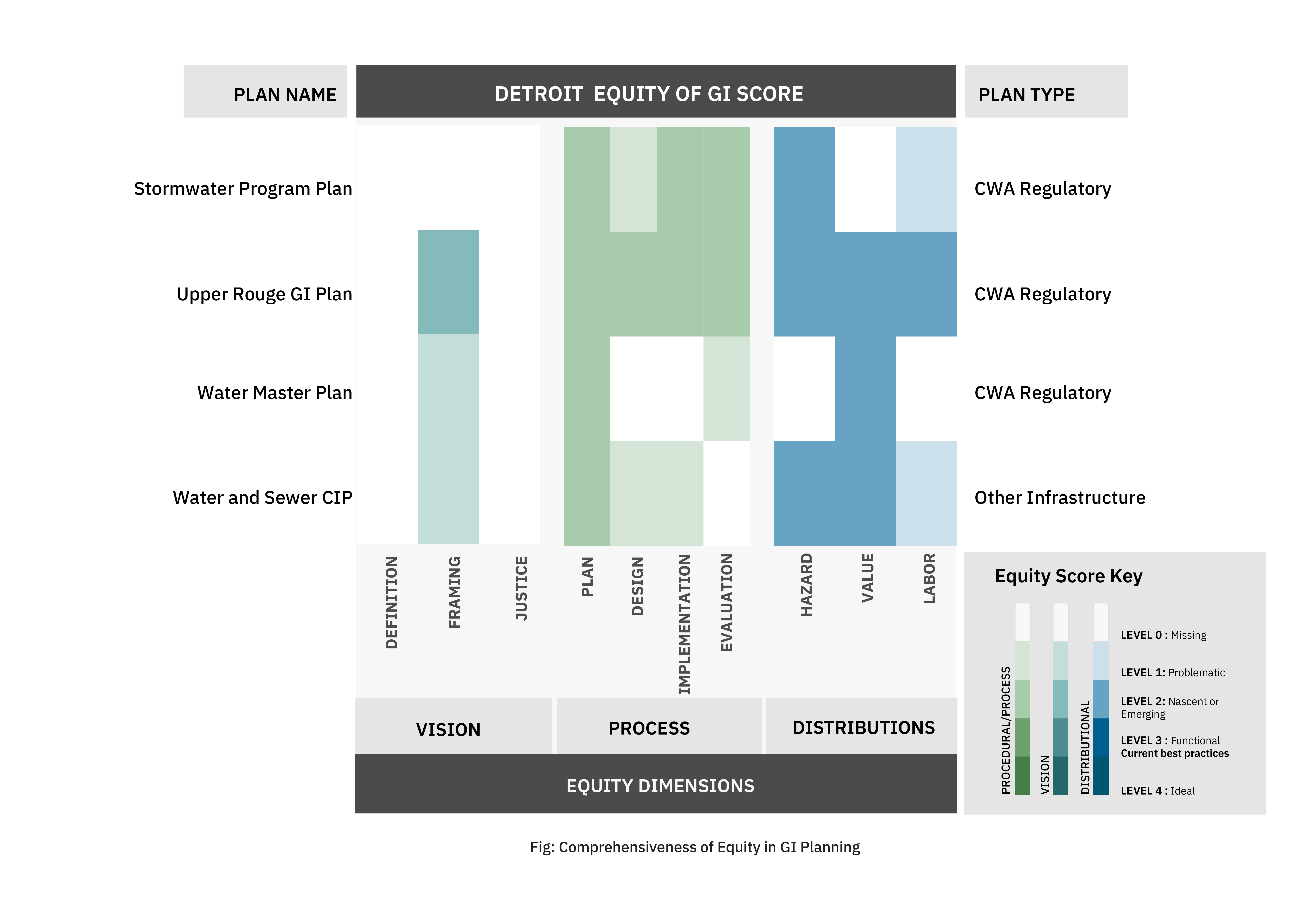

No city-led GI plans in Detroit define the concepts of equity or justice. They also frame the equity implications of existing GI programs weakly or problematically. While there are attempts to be transparent about inclusion in the planning process itself, these attempts often lack mechanisms for accountability and do not fully carry over into the phases of designing, implementing, or evaluating programs. Similarly, plans are inconsistent in their discussion of how GI will manage hazards, add value, and require new forms of labor to be realized.

25%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

75%

seek to address climate and other hazards

0%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

0%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Detroit through Maps

This majority Black city is marked by high degrees of income disparity and racial segregation. The city is characterized by predominantly Black low-income communities facing intense poverty, an affluent and majority White downtown core, and dispersed Black middle-income neighborhoods. Like many midwestern cities in the Great Lakes region, Detroit has very uneven patterns of population density, and high rates of vacancy: 28.5% of housing units are estimated to be vacant. The city is largely impervious with limited forest cover and open space. Incomes are highly skewed, with over 80% of census tracts (as of 2018) having a median income of less than $35,268/yr. The majority of households are rent-burdened, with over 80% of census tracts containing more than 63% rent-burdened households.

How does Detroit account for Equity in GI Planning?

No city-led plans in Detroit define equity or justice, let alone account for equity across all ten equity dimensions. This is striking, given the existence of other community-engaged efforts to create equitable visions for diverse types of GI. While some city-led plans name stakeholders in planning processes, few efforts appear to have been made within current plans to foster community inclusion. Plans have explicit equity implications through their focus on managing combined sewer overflows and surface runoff pollution, as well as some mention of addressing other social values. Labor issues are largely absent or problematically discussed.

Envisioning Equity

In addition to lacking definitions of equity, City of Detroit GI plans weakly frame the relationship between equity and GI. Only the URT GI plan offers any substance and uses a universal good approach focusing on poorly defined social benefits. Other GI plans, such as the Capital Improvement Plan and the Water and Sewerage Master Plan, emphasize the cost of services, cost savings likely due to pursuing GI strategies, and the need to incentivize resource use reductions but do not elaborate on the social benefits of these strategies.

Procedural Equity

Detroit city-led GI plans consistently identify stakeholders deemed relevant by agencies. However, these groups appear largely limited to other city agencies and consulting firms. Aside from the Upper Rouge Tunnel (URT) GI Plan, engagement appears largely limited to the initial stages of planning, with mechanisms to involve affected communities in design, implementation, and evaluation largely absent. The URT GI plan has consistent strategies for outreach but appears to have limited avenues for community inclusion in design, implementation, and evaluation of GI programs and projects. It is noteworthy that as the city seeks to recover from bankruptcy, it has contracted out its overall GI Capital Improvement Process and stormwater programs, essentially privatizing previously public contracts. Official city GI planning in Detroit is largely problematic concerning procedural equity.

Distributional Equity

Plans primarily emphasize mitigating water pollution through improved stormwater management using GI as a hazard management tool and seek to dramatically reduce Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) events. How GI will alter the social distribution of water contamination and CSO events does not appear to be explicitly analyzed in plans.

The URT GI plan underscores that community labor will be crucial for successful GI implementation and commits to helping affected residents raise funds for these responsibilities through grant writing and technical assistance. While there are potential benefits to this approach, such a model places the burden of labor on communities for successful GI implementation and maintenance as well as raising necessary financing, with the city itself dedicating limited resources to community wealth building. The use of international consulting firms to create these plans means the majority of compensation for the labor of GI planning and implementation will not stay in Detroit.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Current city-led GI plans do not meaningfully address equity issues in the City of Detroit. However, the more holistic process for creating the Sustainability Plan, which falls outside the scope of our current analysis as it did not explicitly address GI, seeks to integrate equity into all 43 of the city’s sustainability initiatives. The plan includes a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiative that may represent an opportunity to operationalize systematic approaches toward greenspace planning that contain equity and justice considerations at their core.

Community Groups

Detroit has numerous community groups working towards racial and environmental justice who have been deeply involved in GI planning in the city. Examples of community engaged planning practices in the city include the Detroit Future City Initiative and Strategic Framework which is referenced by city plans, but not in a binding manner. DFC has also served as an umbrella for numerous community-led greening initiatives, such as the Land and Water Works coalition that explicitly seeks to foster engagement between residents and planning agencies. However, despite years of including them on task forces, such as the Green Task Force, The People’s Water Board, city-led GSI plans appear to have limited mechanisms for direct community input in the design, implementation, and evaluation of GSI initiatives. Additionally, formal plans appear to treat existing community-led plans, like the 2012 Water Agenda, as guidelines and not binding initiatives. There thus appears to be a disconnect between robust community-led GI planning practices, and their inclusion in formal GSI plans led by DWSD. Part of the reason for this absence of community voices in GI planning is likely due to GI being only thought of as a stormwater management strategy. Another major reason is likely that outreach is seen as a voluntary component of city-led planning, which is dominated by technical practices. Given ongoing advocacy by community groups for comprehensive approaches for improving community well-being through a more integrative concept of GI, several areas of opportunity exist for community needs to shape city implemented initiatives.

- Centering Community Needs in GI Planning

The green infrastructure concept and initiatives can support existing grassroots-based projects like the celebrated urban agriculture projects implemented throughout the city. These projects, which demonstrate that healthy, nutritious food is a priority in many communities, often do not have city government support, unlike the famous city-sponsored garden projects during the Great Depression. If community needs are centered, emerging urban food systems that support transitions to dense and healthy neighborhoods could be assisted by the incorporation of planned, connected, multifunctional green elements using an integrated GI concept. The importance of GI for community well being can be seen in the numerous volunteer initiatives people have taken to maintain and enhance green spaces. However, this labor often goes uncompensated and can become a burden. Communities can advocate for their care practices to be appropriately valued as labor required to sustain the social, ecological, and physical infrastructures of the city.

2. Pushing the Boundaries of Sustainability

The Office of Sustainability has committed to process and policy improvement to meet the needs of all Detroiters. However, current GI plans, while weakly relying on this ‘good for all’ rhetoric, do not explicitly recognize the persistent environmental disparities in the city and their relationship with racism and classism. The stated willingness to change by city agencies however, may present an opportunity for community groups to help transform existing city policies and procedures into ones that could begin to remedy the environmental and social harms created by past and present decisions. At a minimum, this would require explicitly defining equity and justice goals within official city policies, and putting procedures in place for inclusive planning.

Policy Makers and Planners

Detroit policy makers and planners should consider a systematic approach towards understanding the distribution of diverse green spaces and their relationships with communities across the city. Existing coalitions for non-profits, community groups, and government agencies could be formally supported in an approach for city-wide greening going beyond the use of Green Infrastructure merely as a stormwater management tool. Alongside a systematic approach to GI, equity and justice issues must be addressed in city plans. Below we provide several recommendations to achieve both high-level needs.

- Embracing Landscape-Level Green Infrastructure

Vibrant urban agriculture systems, connected green spaces, and food- and heat-resilient communities would all result from a more cohesive planning framework using an integrative concept of GI. Much of this work is already being done by community advocates. This framework could include initiatives like the Joe Louis Greenway, which currently are not considered under the Green Infrastructure concept. With an integrative GI framework, city policies and plans could more effectively support grassroots initiatives to improve ecological integrity and health and to identify high-priority areas for environmental remediation. The ingredients for a systematic GI approach are present in Detroit but they will need a well-considered conceptual framework to turn them into a successful recipe.

2. Centering Environmental Justice and Equity

Current city plans and emerging initiatives have little to say about deep-seated environmental justice concerns in Detroit. Overall, city plans do not define equity or justice, and only weakly frame equity concerns around the distribution of costs and benefits of GSI programs. City policy makers and planners can proactively address equity issues in GI planning, but doing so would require making community-led planning processes binding on city agencies. As communities continue to organize, policy makers and planners must be receptive to their needs as well as their demands for transformation of the policy making and planning process itself.

3. Building Systems for System Building

Regulatory compliance for both separated and combined sewer system management has been a major driver of GI development in Detroit. These efforts have been aided by a variety of nonprofit actors in the Detroit GI space, and yet no cohesive framework exists for maintaining databases of existing stormwater facilities, never mind the diverse green spaces and parks serving as critical GI. Policy makers and planners should invest resources in building a comprehensive, cohesive, and open planning system for the city’s larger GI network. This system should include a dedicated database with clear ownership of its maintenance and other responsibilities, funding streams for maintaining and enhancing diverse green spaces, and a transparent funding model to ensure the sustainability of urban and streetscape improvements.

Foundations and Funders

Existing nonprofits such as the Sierra Club, Greening of Detroit, The Nature Conservancy, and funders like the Erb Family Foundation have been crucial to promoting blue-green infrastructure initiatives in Detroit and building connections with affected communities. Recognizing that Detroit’s GI system encompasses more than stormwater infrastructure can lead to new opportunities and ways of supporting community organizing efforts as they seek to revitalize communities while preventing housing displacement and making green reparations. These efforts can be combined with existing well-funded racial justice initiatives.

1. Transformative Justice through Just Transitions and Appropriate Technology

According to some analysts, Detroit could be poised for economic transformation through the enactment of a municipal level Green New Deal. The Frontline Detroit Coalition has charted a course toward this goal by reframing the needs of Detroit communities around the intersectional issues of climate and social justice. However, specific plans for a just transition and an economic transformation addressing both the causes and outcomes of current decision-making, are lacking. Under the umbrella of an equitable GI framework, funding community-led efforts to plan and design smaller-scale systems for energy, water, food, transportation, and organizing could be a unifying and crucial piece of larger economic transitions. Those types of transitions have historically been driven by the comings and goings of external investors.

2. Building Momentum to Transform Institutions

Numerous community-led initiatives - described above in the community section - have sought to have greater input in formal city-led planning practices. While some task forces exist to foster community input into city planning, these have room for further development. Foundations and funders can support initiatives with explicit goals to include community organizations and members directly in GSI decision making. At a minimum, this would include having majority representation from intersectional community organizations such as those addressing disability and racial justice. Seeds of such ‘people-centered’ vs organization-focused approaches are present in programs in Detroit, such as the New Economy Initiative and the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan’s Detroit Innovation Fellowship. However, focusing on individuals, instead of community-building, can shift attention away from the political structures and institutions creating racial wealth inequality in the first place. Transforming institutions can be accelerated by supporting movements seeking formal policies for inclusive planning.

Closing Insights

Equitable GI planning requires a deep rethinking and restructuring of urban governance. Addressing systemic racism is possible by building community wealth and supporting the self-determination of marginalized communities to confront and rectify historical and ongoing harms. Existing GI approaches in Detroit would benefit from explicitly analyzing and targeting inequalities in exposure to environmental hazards, creating local employment opportunities, fostering inclusive and collaborative planning in order to incorporate numerous community based GI efforts into official city-led initiatives.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.