DENVER

Incorporated 1858

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 154.9 sq. miles

- 693,417 Total population

- 4523 People per sq. mile

- 0% Forest cover

- Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands

- 14.2% Developed open space

- $63,793 Median household income

- 10% Live below the federal poverty level

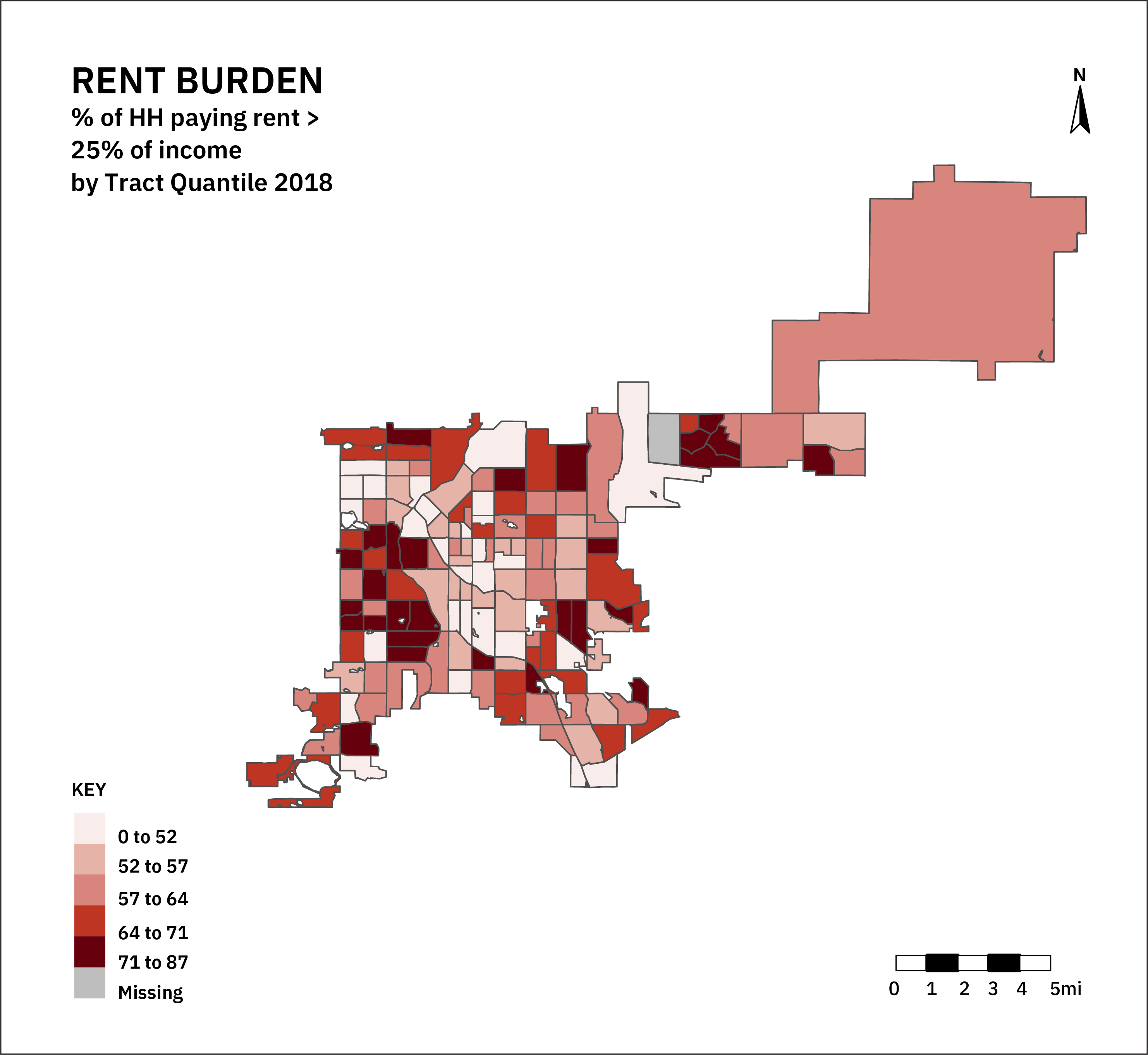

- 60.1% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 6.3% Housing units vacant

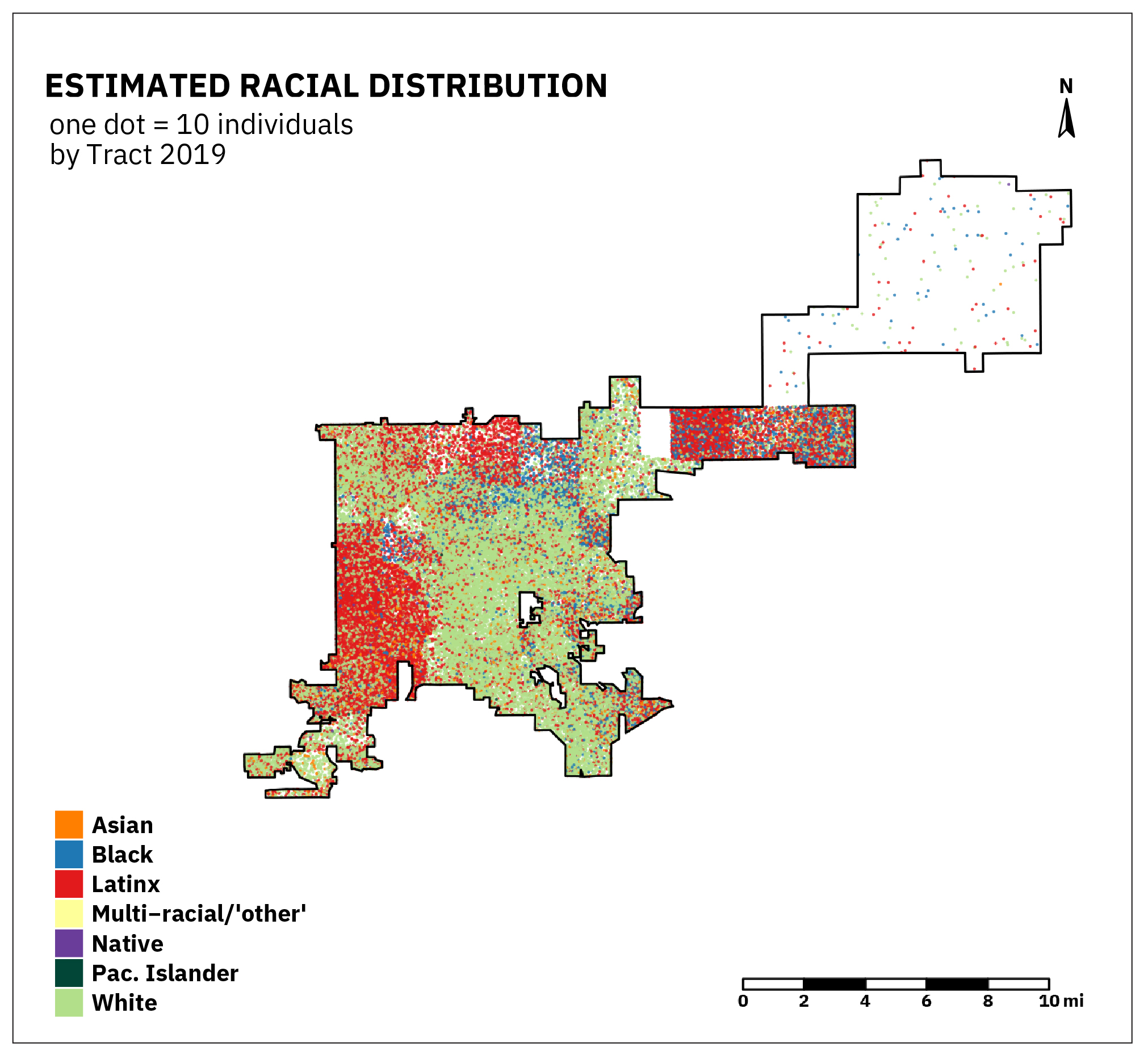

- 0.5% Native, 54.2% White, 8.9% Black, 29.9% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 3.6% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The City of Denver occupies the homelands of Arapahoe peoples. The city owes its existence to a series of contested treaties and the massacre and forced removal of Native people, who maintain an active presence in the city today and continue to fight for their rights. A small city for much of its early history, Denver has experienced rapid economic and demographic growth since the 1980s.

While the metropolitan region has become increasingly developed, the urban core faces challenges of uneven investment and the reuse of industrial space, leading to large scale redesign and redevelopment efforts. These include a major revitalization of its river corridor and an emerging city-wide green infrastructure network integrating stormwater facilities with parks and recreation spaces. However, growth has been highly unequal, and there are significant issues around housing affordability and displacement, racial justice, and economic inequality.

Green Infrastructure in Denver

Denver has a diverse set of plans addressing GI. Alongside the dedicated GI Strategy, which largely addresses stormwater management, the concept is employed to guide landscape conservation and integrative planning efforts. The Comprehensive Plan and Neighborhood Planning Initiative lay out a city-wide vision for interconnected parks, green spaces, and stormwater infrastructure systems. All the plans examined in Denver defined GI, aside from the current Capital Improvement Plan, which nevertheless supports a wide range of GI-related programs across the city.

In line with the breadth of concepts at play, Denver plans address the range of categories of GI types, although some specific types, such as wetlands, trails, and green streets are lacking, indicating that more green elements could be included in the city-wide definitions of GI.

Denver plans focus on the environmental and technological functions of GI. These include an emphasis on managing stormwater, in addition to supporting ecological processes, regulating heat, improving air quality, sequestering carbon, and improving the overall functionality of the built environment.

Denver GI definitions emphasize a narrower range of benefits than half the cities we examined and did not appear to frame GI as contributing significantly to urban sustainability. Plans defined benefits according to a range of social functions, including health and livability, along with safer transportation networks and more timely infrastructure development.

Key Findings

Among all plans in our analysis, Denver plans clearly lead in terms of thinking through equity issues around health disparities and explicitly targeting GI programs.

83%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

17%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

67%

seek to address climate and other hazards

67%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

67%

define equity

17%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

50%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Denver through Maps

Denver has grown tremendously over the last several decades due to the annexation of a part of Adams County, CO when Denver International Airport was constructed. The city has dense commercial, residential, and industrial development along the central river corridor, with some outlying areas also having a mosaic of high-intensity development. Otherwise, the city is characterized by sprawling, low-density, largely single-family housing. The city is highly segregated between Latinx, Black, and white communities, mirroring patterns of rent burden and income inequality. Vacancy rates appear more idiosyncratic, with overall rates lower than many of the cities examined in this study. Despite having street trees, there are no continuous patches of forest cover within the city proper.

How does Denver account for Equity in GI Planning?

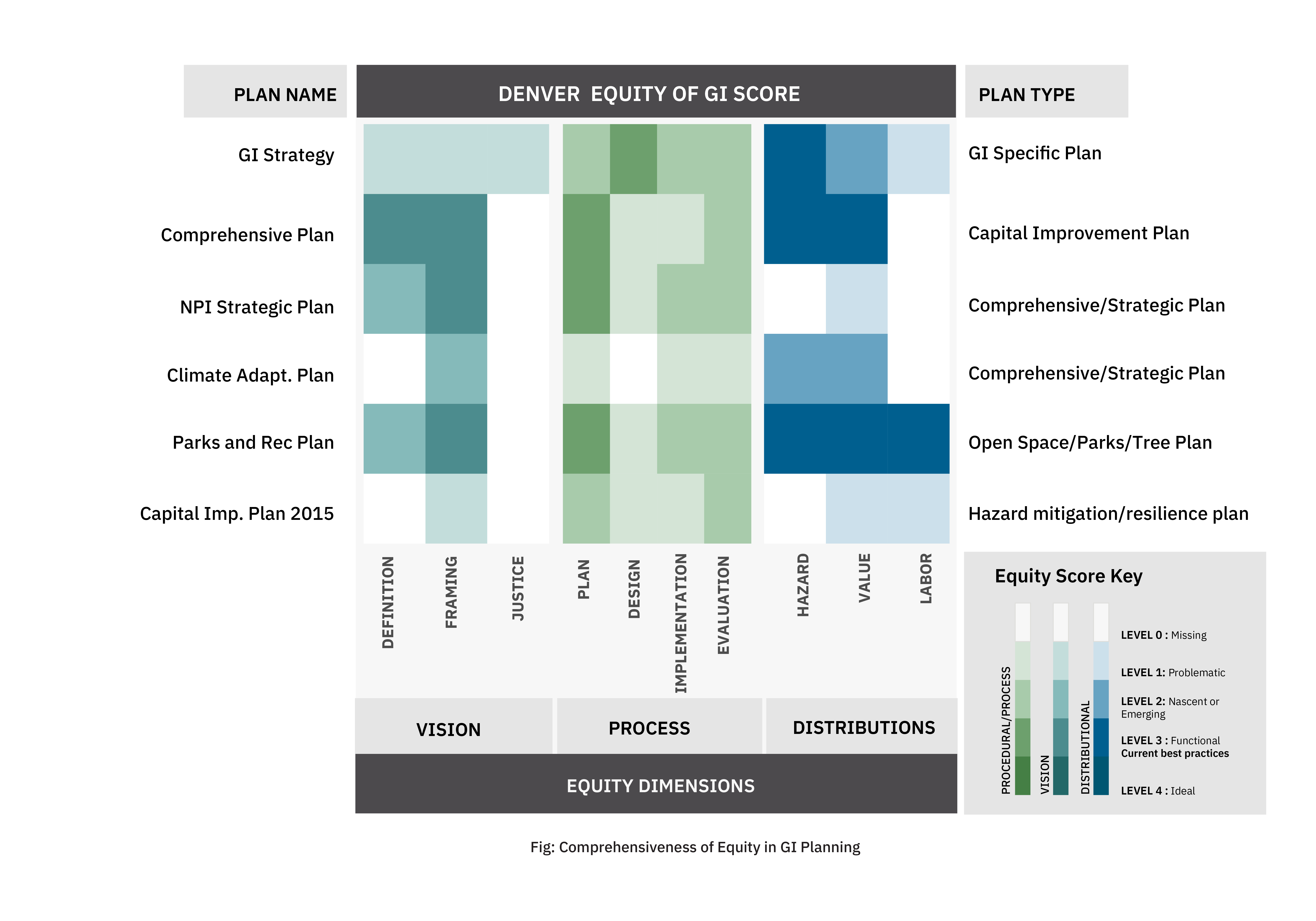

The Denver GI strategy addresses all aspects of equity evaluated using our screen. The city’s GI siting framework centers health disparities connected to environmental hazards; it aims to use GI to mitigate risks that disproportionately harm residents’ health in low-income areas. Many of the plans define equity in relation to GI but only the Comprehensive Plan contains a robust definition addressing procedural and distributional components. Yet, it falls short of the ideal by not explicitly addressing the need for justice. Another strong example is the Parks and Recreation Plan. It touches on 9 of our 10 screening categories and contains current best practices in examining the distributional components of equity. Overall, though, mechanisms for including input from communities are lacking, and a vision for GI that includes a robust consideration of justice is not expressed in any plan.

While Denver plans emphasize inclusion, they have gaps in how to involve affected communities in design and implementation. In addition, there are considerable absences in how justice is conceptualized and addressed. Thus, despite an attempt to systematically prioritize underserved communities, current methods of siting GI, aside from parks, are problematic.

Envisioning Equity

Denver plans more consistently define equity than many other cities, with a particularly strong emphasis on health equity. However, health is often framed in largely environmental and lifestyle terms, completely omitting the ‘Social Determinants of Health’ framework. While half of Denver’s plans examined frame equity in robust ways, only the GI strategy mentioned justice at all. While the term ‘equity’ may be noted several times, a lack of definition and functional metrics that address justice contribute to difficulties in applying the concept. The Comprehensive Plan is particularly problematic in that environmental justice is absent from the plan, despite having been raised as a concern in the 80x50 stakeholder report.

Procedural Equity

The GI strategy emphasizes inclusive design, but falls short on how it involves communities in other stages of the GI lifecycle. While half of the plans examined in Denver (including the Comprehensive Plan, Neighborhood Planning Initiative, and the Parks and Recreation Plan) contain current best practices for inclusive planning, they problematically or inconsistently involve communities in the design, implementation, and evaluation processes.

Distributional Equity

Every Denver plan seeks to improve the equity of urban land values distribution, although neither the NPI nor the Capital Improvement Plan offered a strong framework to do so. The Parks and Rec Plan consistently used current best practices in identifying how GI could equitably mitigate hazards and add value for urban residents. The Parks and Rec Plan also stood out as one of the best plans we examined in terms of purposefully structuring hiring and recruitment to create a workforce that would be representative of the communities the agency serves. The Comprehensive Plan attempted to robustly and equitably consider hazards. They used current best practices by explicitly seeking to improve the equity of the distribution of multiple GI values. However, the plan does not contain any actionable strategies for addressing labor equity related to GI projects. Thus, as in other cities, GI plans, on the whole, show intent to address equity issues, yet do so in a fragmented and inconsistent manner. Please see below for several key recommendations that offer a systemic approach for improving the GI and equity concerns in Denver planning.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Denver’s strength with equity lies in its formalization of equity criteria in its GI planning efforts. However, these equity-forward approaches are largely ahistorical, fail to recognize justice, and lack mechanisms for transforming planning so that historical injustices are not recreated by current practices. Addressing the shortcomings in procedural justice, the democratization of planning, the distributions of services GI seeks to provide, and the labor required to ultimately realize them, may help to align the diverse efforts of the numerous nonprofits, city agencies, and philanthropic organizations that are active within the city and its planning efforts.

Community Groups

Denver has a rich ecosystem of community groups and statewide organizations working on racial and housing justice. Given the observed relationship between housing displacement, affordability, and green improvements, the implementation of a city-wide green infrastructure strategy will have relevance to advocates for social and racial justice. Organizations like Groundwork Denver have been supporting communities in greening initiatives to address environmental justice issues which are also discussed by city plans. There is a need for sustained community organizing to confront the intersectional issues of housing, environmental hazards, climate resilience, and economic justice. Efforts to address these issues may benefit from the following considerations.

1. Windows of Opportunity for Transformative Change

The current administration of Michael B. Hancock has a strong equity platform. The Agency for Human Rights and Community Partnerships has been tasked with implementing it by educating city agencies and staff about the impacts of their work on racial equity. Such an approach is certainly an improvement over ‘race blind’ approaches, and yet does not address fair and transparent inclusion in decision making. Without transforming processes of city agency decision-making, additional metrics of agency impacts have limited impact on agency behaviors. Transformative planning and governance include direct participation in the prioritization, budgeting, and evaluation of city agency initiatives.

2. Coalitions for Fair Housing and Greening

Within the state of Colorado, several organizations have built coalitions to address housing justice issues. At the core of these campaigns is an effort to repeal the statewide ban on rent control. Advocates for urban greening and environmental justice may benefit from recognizing and organizing for relationships between accessible and affordable housing, urban environmental quality, and labor justice. Given that state and county policy must change to support more equitable development, advocate organizations could support transformative policy platforms, such as comprehensive policy packages reminiscent of a state or county level Green New Deal.

3. Holding Equity Planning Accountable

Denver has made bold commitments to equity within its Comprehensive, GI, and Parks Plans. However, plans do not transparently operationalize equity. In the case of the ‘Game Plan’ social justice is reduced to a metric of income in basin level prioritization, and then eliminated from sub-basin level prioritization. Community organizations can demand that Denver planners and policy makers provide more meaningful metrics of equity, including processes for robust inclusion of affected communities in city planning and policy.

Policy Makers and Planners

As noted above, Denver plans do not reflect the equity frameworks or aspirations of the current city Administration, and inconsistently define and operationalize equity concerns. We offer our insights to the new city agencies and think tanks tasked with addressing these issues to transform upcoming city planning and greening initiatives. Our framework provides for a robust conceptualization of equity from the creation of plans through their implementation and evaluation, with careful consideration of the multi-dimensional impacts of planned activities on values, hazards, and labor markets. Policy makers and planners concerned with equity issues can utilize this general framework, along with three major arenas for action specific to Denver City and County.

1. Operationalizing Equity in Prioritization and Beyond

Denver plans notably seek to include social equity as a criterion for the siting of GI. However, they only examine social equity as a function of income and health disparities. Plans weakly articulate the underlying social conditions that produce disparities in income and health. Without a more operational framing of what produces inequity, plans attempting to ameliorate environmental disparities will not succeed. Denver has an opportunity to think and act holistically with respect to changing social structures producing inequity, and this should be reflected in more robust criteria for defining social and environmental inequities and prioritizing green infrastructure investments addressing these underlying social disparities. The Denver Game Plan puts forward a workable framework for this type of work. The holistic consideration of how cost effectively GI manages hazards, provides diverse benefits, and provides opportunities for skilled labor development should extend to other green infrastructure assets besides parks and recreation lands.

2. Fitting solutions to Place, Across Scales and Generations

Denver has unique challenges for a major metropolitan area situated in a high altitude and arid environment. While the national land cover database indicates that there is no forest cover within the city limits, the City does have property holdings and influence over a regional ecology that includes forests. However, this larger green infrastructure network, including the city’s western slope water supply system, does not receive attention within its GI plans, and there appears to be limited integration of regional strategies for long-term sustainability within city green infrastructure initiatives. Denver planners and policy makers should consider the intergenerational equity of current decision-making, meaning the long-term consequences of current development strategies. They should also consider how the sprawling growth of Denver and other front-range communities will incur long-term ecological and social debts through distributed and highly costly forms of infrastructure. The City has the opportunity to make decisions about urban form and local resource utilization that may prevent longer-term stresses, especially on water systems. However, given that Colorado water law prevents many rainwater capture initiatives, addressing water sustainability in Denver may also require shifts in state-level policy.

3. Scaling Equitable Growth

Denver has relatively low poverty levels compared to many similar sized cities. However, the majority of households are rent-burdened within the city, and low vacancy rates indicate that the housing market overall is highly constrained and not currently meeting the demand for affordable housing. At the same time, surrounding counties have developed rapidly, and many reports indicate that significant displacement of lower-income populations has already occurred. Given that cities require workers of many different classes to function, these larger-scale patterns of segregation are also unsustainable. Current efforts to radically transform housing affordability, led by grassroots organizations, are likely required to prevent further displacement of low-income communities from new developments that incorporate green infrastructure.

4. Equitably Tracking Outcomes

In addition to the many metrics of success used by Denver’s GI plans, communities should have direct avenues to evaluate the success of city initiatives and programs. Relying on census and American Community Survey data is too inconsistent and too sparse for real-time tracking of the impacts of particular programs, policies, and projects. By the time significant signals are detected, neighborhood change may be irreversible. The city government should identify procedures to meet communities where they are at and provide resources for their meaningful participation in the evaluation of implemented city programs.

Foundations and Funders

Denver has embarked on promising initiatives to address systemic racism in city government. However, given the extensive displacement of low-income and predominantly POC populations, a primary struggle in Denver is reclaiming areas for affordable housing and protecting other communities from further displacement. Some initiatives, like those led by Groundwork, take a community-first approach for greening to mitigate climate hazards. Yet such programs appear to receive limited support from the city government despite the potential that exists within the neighborhood planning initiative. Other planning processes such as Blueprint Denver, the Neighborhood Planning Initiative, Denver Right, and Denver Moves all center community engagement with city agencies. The success of these initiatives will depend on how effectively organized communities can steer city agency activities and hold them accountable in implementation.

- Supporting Community Organizing

While there are nonprofits in Denver working on intersectional racial and environmental justice and housing issues, foundations and funders could strategically invest in grassroots groups and coalitions to build community capacity to steer the aforementioned planning processes. Capacity building is multi-dimensional, and requires care and harm reduction as a first step to free up community energy and attention to build positive futures. Such an approach must overcome the hurdles to successful participation in collaborative planning processes. These include a lack of material support, compensation, and childcare for participants, non-collaborative scheduling, power imbalances, cultural and language barriers, and ongoing structural violence. Working in collaboration with communities and city agencies, funders can be key players in building a care economy and coalitions that enable equitable participation in planning for desirable urban futures.

Closing Insights

Denver has taken a multi-dimensional and integrative approach to green infrastructure planning and is one of the leading cities attempting to incorporate equity into those plans. However, much work remains on how to successfully operationalize equity and justice principles in city programs, address the structural causes of inequity and injustice, and build community capacity to participate in and influence city decision-making and planning. In one of the country’s fastest growing metropolitan areas, the city’s forward-thinking initiatives present an opportunity to further evolve best practices and to build a more sustainable and just city.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.