Philadelphia

Incorporated 1682

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 134.2 sq. miles

- 1,575,522 Total population

- 11,737 People per sq. mile

- 7.4% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 11.7% Developed open space

- $43,744 Median household income

- 19.6% Live below federal poverty level

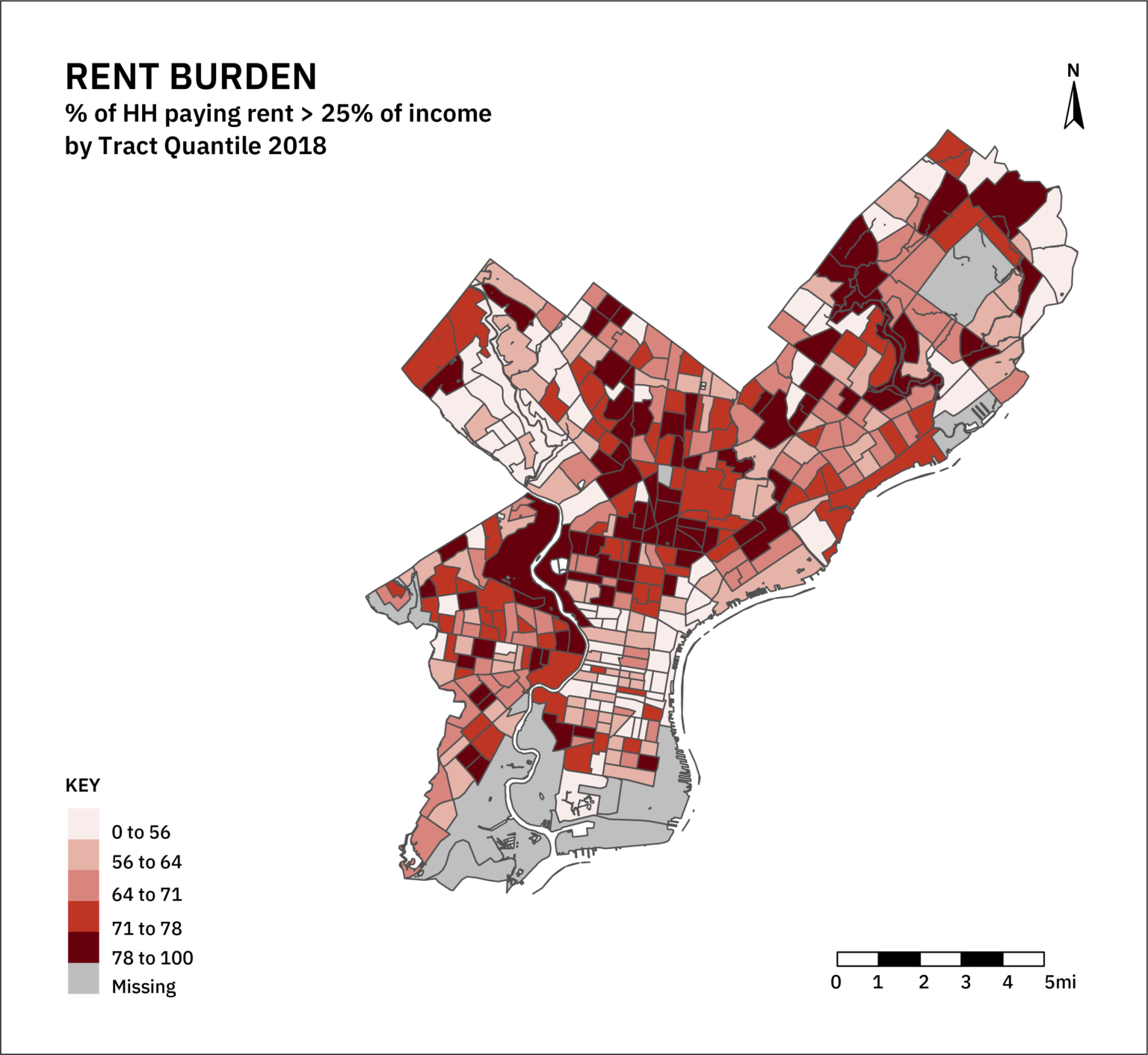

- 66% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 12.9% Housing units vacant

- 0.2% Native, 34.5% White, 40.8% Black, 14.7% Latinx , 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 7.2% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

Philadelphia occupies lands of the Lenape Haki-nk (Lenni-Lenape), lands stolen during the founding of the colony of Pennsylvania by William Penn, and subsequent waves of intensive warfare and dispossession that remain largely unacknowledged in the state’s history. The port city grew over time into a center of industrial innovation and wartime manufacturing but has struggled to reinvent itself in the face of US manufacturing decline. However, the City of Brotherly Love has experienced major economic revival and growth since the 1990s.

Like other cities, growth has been highly uneven, with many communities experiencing significant housing displacement and gentrification. Ambitious redevelopment and environmental programs have reshaped the city’s physical and social landscapes. Persistent segregation and uneven exposure to environmental hazards have been structured by redlining, urban renewal, and flight from the urban core. Like other East Coast cities, sea-level rise, increasing heat waves, and other extreme weather events impose new challenges on aging infrastructure.

Green Infrastructure in Philadelphia

Philadelphia has long been recognized as a green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) leader and innovator through its ‘Green City’ program. The city has sought compliance with combined sewer system regulations through ambitious city-wide GSI programs. These programs have been integrated into numerous area master plans as well as the City Climate Resilience and Sustainability plans. Even with such extensive GSI planning, the city’s GI plans do not robustly articulate an explicit ‘green infrastructure’ concept. When GI is defined, plans emphasize efforts to expand street tree plantings and green streets, alongside efforts to green schoolyards, and expand urban agriculture.

Philadelphia GI plans focus on providing environmental functions and the benefits of improving water quality, livability, the health of residents, and reducing the cost of infrastructure services.

Key Findings

Despite several plans explicitly referring to the need to address equity in GI planning, plans have numerous gaps. These include the failure to create mechanisms for meaningful public involvement. Plans examined do not generally define equity or justice issues, and often problematically frame and discuss equity issues. The city’s focus on private sector-led implementation is problematic, as the real estate market and property value become the drivers of how GI will rearrange urban hazards and what makes the city a desirable place to live. Finally, labor issues are questionably or incompletely addressed.

13%

explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

15%

recognize that some people are made more vulnerable than others

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

54%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

8%

define equity

15%

explicitly refer to justice

77%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

23%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Philadelphia Through Maps

Philadelphia is a densely populated city with highly uneven access to larger green spaces. Census tracts with lower incomes, high rent burden, and high housing vacancy cluster together and appear correlated with race, similar to many cities with legacies of systemic disinvestment in communities in the urban core. Dense redevelopment and housing displacement have been concentrated downtown and along the riverfront.

How does Philadelphia account for Equity in GI Planning?

Despite numerous green stormwater infrastructure planning efforts spurred by the need to comply with Clean Water Act regulations, which includes the integration of GSI in several local area master plans, GI plans in Philadelphia do not robustly address equity or justice issues.

Only one plan defined equity and no plans defined justice. Plans weakly or problematically framed equity issues, with several not discussing equity issues at all.

Despite an admirable emphasis on community inclusion in planning, plans describe limited means for community inclusion through design, implementation, and evaluation, with some notable exceptions.

All GI plans in Philadelphia explicitly seek to rearrange the distribution of urban hazards while adding value. Only half of the plans acknowledge the labor required to do so, often in problematic ways.

Envisioning Equity

The Greenworks Sustainability Plan was the only GI plan in Philadelphia defining equity. The plan seeks to improve the quality of life for all city residents, and intends to use its Greenworks Equity index to “develop programs to support communities that are not currently enjoying the benefits of sustainability.” We found this targeted universalism approach backed by metrics to be admirable, but compared to other cities, it falls short in identifying and addressing the causes of disparities in community well-being and sustainability. Other GI plans in Philadelphia adopt similar framings, generally focusing on improving access to environmental amenities and supporting community revitalization, but do not address the potential risks of relying on private sector-led redevelopment in marginalized communities.

Procedural Equity

Like in many other cities, Philadelphia GI plans frontload community participation in the planning process with limited follow through to design, implementation, and evaluation. The Greenworks Sustainability Plan, Green City Long Term Control Plan, and Comprehensive Plan all claim overwhelming public support and demonstrate current best practices in surveying public opinion. Yet their documentation leaves much to be desired, offering no evidence that those who face the largest risks of plan implementation have had their needs and concerns addressed. Despite the Green City program embracing an adaptive management model, and devoting an entire plan to the evaluation of city-wide green stormwater infrastructure programs, notable gaps remain in how the concerns of communities will be addressed. Area plans contain formulaic GI community engagement mechanisms, with limited documentation of community involvement or outreach, and they operate on timescales that preclude addressing displacement. Furthermore, the comprehensive plan process is largely restricted to participants choosing between projects in resource-limited scenarios. Participants are not typically asked to provide input to frame the needs, goals, and mechanisms of GI planning, implementation, and maintenance.

Distributional Equity

Philadelphia GI plans highlight the pitfalls of primarily focusing on stormwater management to the exclusion of other considerations. While plans generally seek to reduce or eliminate combined sewer overflows, they limit what other hazards can be addressed by GI. On a hopeful note, the Adaptive Management Plan states that city agencies are actively researching the effectiveness of GSI to deliver multiple benefits.

Area plans deviate from this stormwater focus to some extent by discussing contextual hazards of sea-level rise, flooding, and climate change but they do not discuss the intersectional or social dimensions of why some groups face greater exposure to hazards, or how they have been made more vulnerable to them. One update to the Long Term Control Plan did engage in a public survey exercise to evaluate the perception of GI’s role in reducing a larger range of hazards than those related to stormwater. Unsurprisingly, since multifunctionality does not appear to be a core design concept in Philadelphia GSI, residents did not perceive existing GSI to provide non-stormwater functions. In addition, implying that GSI installations can reduce crime, without addressing the fact that these programs, coupled with redevelopment, may lead to the displacement of oppressed groups is highly problematic.

Value-wise, GI plans in Philadelphia explicitly engage in rationalizing universalist approaches. They go so far as to say that targeted, need-based investment would lead to the uneven and unfair implementation of the city’s GSI programs, thus preventing restorative approaches. Plans also put forth the demonstrably false idea that universal increases in property value will benefit all residents. The city prioritizes GI installations by areally-weighting impervious cover to select locations. There does not appear to be an effort to understand the social implications of this type of approach. Plans’ reliance on private developers to lead GSI implementation appears to be a misappropriation of equity language with the result of supporting approaches proven to have uneven social consequences.

GSI programs also appear to be limited by a refusal to consider reducing space for automobiles in the city, as they are framed as conflicting with other green connectivity initiatives. Thus GSI and alternative transit and parks are made to conflict with one another, but not with the grey infrastructure systems that make GI necessary. Philadelphia GI plans lead on examining the administrative issues and benefits of a more flexible GSI approach for managing combined sewer overflow issues. Labor-wise, the Green City program’s Maintenance, Adaptive Management, and Evaluation Plans acknowledge that continued upkeep is crucial for GSI’s successful operation. However, none of the plans propose actively identifying how the various types of labor required by GI and GSI can be leveraged to build community wealth.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Like many cities examined in this set, the plans do not reflect current efforts or initiatives by government agencies, community groups, and funders to address long-standing social and environmental justice issues. Numerous gaps in addressing equity issues in Philadelphia’s GI plans have been identified in this analysis. See below for city-specific recommendations to guide the inclusion of equity and justice considerations in the implementation and improvement of Philadelphia’s GI plans and programs.

Community Groups

Philadelphia has long been a center for oppressed and marginalized communities to positively and collaboratively reimagine urban futures for themselves in the face of historical, continued, and often violent, oppression. The current turn towards addressing equity in city government policies and programs through the creation of the Mayor’s Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion presents an opportunity to expand the conversation about racial and environmental justice, and to restructure institutions to meet the needs of marginalized communities. Our recommendations provide ways in which GI planning efforts can be positively influenced by, and support, ongoing efforts led by Philadelphia’s diverse grassroots organizations and their initiatives.

1. Make GI planning address community environmental justice

City administration efforts to celebrate environmental justice month bolster a narrative of personal responsibility and accountability that can aggravate inequalities and obscure the systemic causes of environmental harms. While the city’s GSI programs may cost-effectively manage its long-running combined sewer overflow problems (itself an environmental justice issue), other challenges, related to flooding, heat, sea-level rise, and persistent inequalities in health outcomes and exposure to toxic chemicals and pollution, require a broader transformative approach. Such an approach would utilize a more robust conceptualization of GI that focuses on the relationship between social, ecological, and technological systems. However, this approach must be based on needs articulated by, and for, the community. To that end, community groups can advocate for a transformative approach simultaneously addressing environmental hazards and social justice which will require going beyond storm and sewer system management decisions.

2. Amplify Housing Concerns

While the city needs to address its water pollution and other environmental justice issues, it cannot do so at the cost of current residents, especially those who have already borne the brunt of environmental harms. There is a track record of displacement in Philadelphia following large-scale GSI implementation, especially redevelopment projects led by the private sector; because of this, community groups working on housing issues have a common cause of concern with environmental justice advocates. This shared interest could provide a foundation for community power-building and better outcomes for both housing and environmental justice organizing.

Policy Makers and Planners

Philadelphia green infrastructure planning remains limited in scope by the green stormwater infrastructure concept. The city would benefit from planning across infrastructure systems and incorporating parks and open space planning into a more holistic approach. As in other cities, there is a need to focus on how to use GSI programs to build community wealth, recognizing that treating communities as experts requires compensating them as such. There is also a need to be more clear about what equity and justice mean in the context of city-wide GI strategies. We elaborate on these recommendations below.

1. Broadening GI and Specifying GSI

Philadelphia has numerous initiatives to improve access to green spaces and environmental amenities somewhat integrated with GSI programs. Yet, these do not appear to have an overall conceptual coherence or shared framing. Planners and policy makers should adopt a broader definition of GI to integrate various elements of the urban ecosystem within a coherent policy and planning framework. An integrated approach, such as the one described on our framework page that is being implemented by some of the cities identified within this project, will allow for a more coherent and balanced approach towards green space, ecological restoration, parks, and GSI planning. This, in turn, will allow planners to meet a much larger number of community needs than with GSI tools alone.

2. Embedding the Triple Bottom Line

A significant analysis of triple bottom line benefits was performed by the Water Department within its long-term control planning process. However, there does not seem to be a framework for evaluating if those benefits will be realized; this is a substantial area for improvement. Directly engaging communities to determine if social equity goals are being met in their experience is the only way to embed a triple bottom line approach. When evaluating city initiatives, relying on a city agency or an appointed commission to make those determinations replicates existing inequalities in whose experiences and voices count.

3. Centering Community-led Planning to Address Housing Displacement

The Model Neighborhood Program has fostered a more community-centered planning approach in Philadelphia’s GSI planning. This program lacks clarity in important ways, in that the many mechanisms for community inclusion are in development. It is also unclear how current agencies will partner with Philadelphians to implement GSI in a cost-effective manner that meets community needs. Adding transparency to these mechanisms is the first step in centering community needs to address the risk of housing displacement occurring in Philadelphia, which appears to be driven by the spatial and social context of GSI projects.

4. Improving Public Evaluation Processes

The City of Philadelphia Water Department’s Green City Evaluation Plan, published in 2016, was preparing a street survey of 'customers' as part of the evaluation of the plan’s effectiveness. However, it is not clear if the ‘customers’ include renters and if they address the broader set of concerns around large-scale GSI implementation, including neighborhood change and housing displacement.

The Evaluation Plan does not report demographic information. The plan acknowledges this fact as well as the limitations that are created by this exclusion. For example, there is no way of knowing whether feedback solicited from the public is representative of the general population. In addition, the survey has predetermined response bins, not allowing for open text responses, and does not appear to be designed to allow for statistical analysis of how GI is perceived by different types of individuals and communities.

Future evaluation efforts should be transparent about the demographics involved, and make a concerted effort to include underrepresented groups, including offering compensation for survey completion and participation in more robust evaluation procedures. It should also be made clear that survey results will adjust how the city operates its programs. Additionally, allowing for open form responses provides an avenue for communities to express more comprehensive ideas about the perceived and experienced impacts of GSI programs and other related projects that affect them, such as redevelopment.

5. From Facilitating Redevelopment to Wealth Creation

Most GI plans in Philadelphia were silent on labor issues. This contrasts sharply with their consistency in framing redevelopment as the primary vehicle of wealth creation associated with GI. However, city GI plans state that they were 'exploring' options for training, upskilling, design, and hiring with local businesses. This signals a major opportunity to create a more cohesive policy around 'green' redevelopment that works across core programs (e.g. through schools into jobs training) and focuses on capturing the value of contracts locally rather than through multinational firms as other cities (e.g. Milwaukee and New Orleans) intend to do - a key area of recommendation.

6. Addressing differential vulnerability

The stated goals and approaches to address equity in Philadelphia GI plans do not include differential vulnerability to multiple hazards which can be remediated through GI and GSI. Policy makers and planners should advance approaches that center the needs of residents and communities who have been made more vulnerable to the effects of climate change and other human-made hazards. An equity-forward GI approach must go beyond targeted universalism and incorporate restorative and transformative justice within a just transition framework.

Foundations and Funders

We recommend the embrace of a broader and more integrative concept of GI. Numerous nonprofit groups have been involved in the creation and implementation of Philadelphia’s GI plans with an emphasis on improving environmental quality. This is reflected by the participation of multiple watershed partnerships, environmental NGOs, and business networks in GI programs. Organizations like the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society have also contributed to GI installations, by incorporating native plants into environmental designs. This constellation of environmental and business advocacy groups should be broadened to include those working on social justice issues, in the spirit of 21st-century conservation approaches that simultaneously address necessary infrastructure improvements and environmental justice. These more integrated efforts provide new opportunities for existing GI project funders, such as the William Penn Foundation. In combination with the above recommendation, we recommend involved organizations adopt an intersectional approach in their relationships with communities and environmental initiatives.

1. Supporting Intersectoral Organizing

Intersectional approaches towards environmental improvement using GI must take into account the totality of a community’s concerns and desires for a better future. It has been a common refrain in watershed associations and environmental groups that housing concerns do not fall within their mandate. At the same time, these groups are often awarded grants because their work is in marginalized communities. What good are environmental interventions and improvements in these communities if long-time or existing residents can no longer afford to live there? This intersectional type of approach is unlikely to succeed without communities themselves being organized as effective advocates. Foundations and nonprofits should support building deeper, more committed relationships in communities and invest in grassroots-based organizations that are best suited to advocate for the needs of their communities. Already, organizations like EcoWURD have documented and amplified grassroots environmental justice efforts, an excellent example of the type of community infrastructure that could be further supported by philanthropic and nonprofit organizations.

Closing Insights

Philadelphia’s GI plans clearly indicate that it is a leader in advancing city-wide approaches to embedded green stormwater infrastructure in the urban landscape and neighborhood-level planning. A shift towards a more integrative GI approach will be needed to address the deeper and persistent injustices and inequalities within the city. This shift must occur in genuine collaboration with grassroots organizations to embed just transition practices within institutional efforts of deep urban greening.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.