SAN JUAN

Incorporated 1521

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 46.4 sq. miles

- 331,165 Total population

- 8,377 People per sq. mile

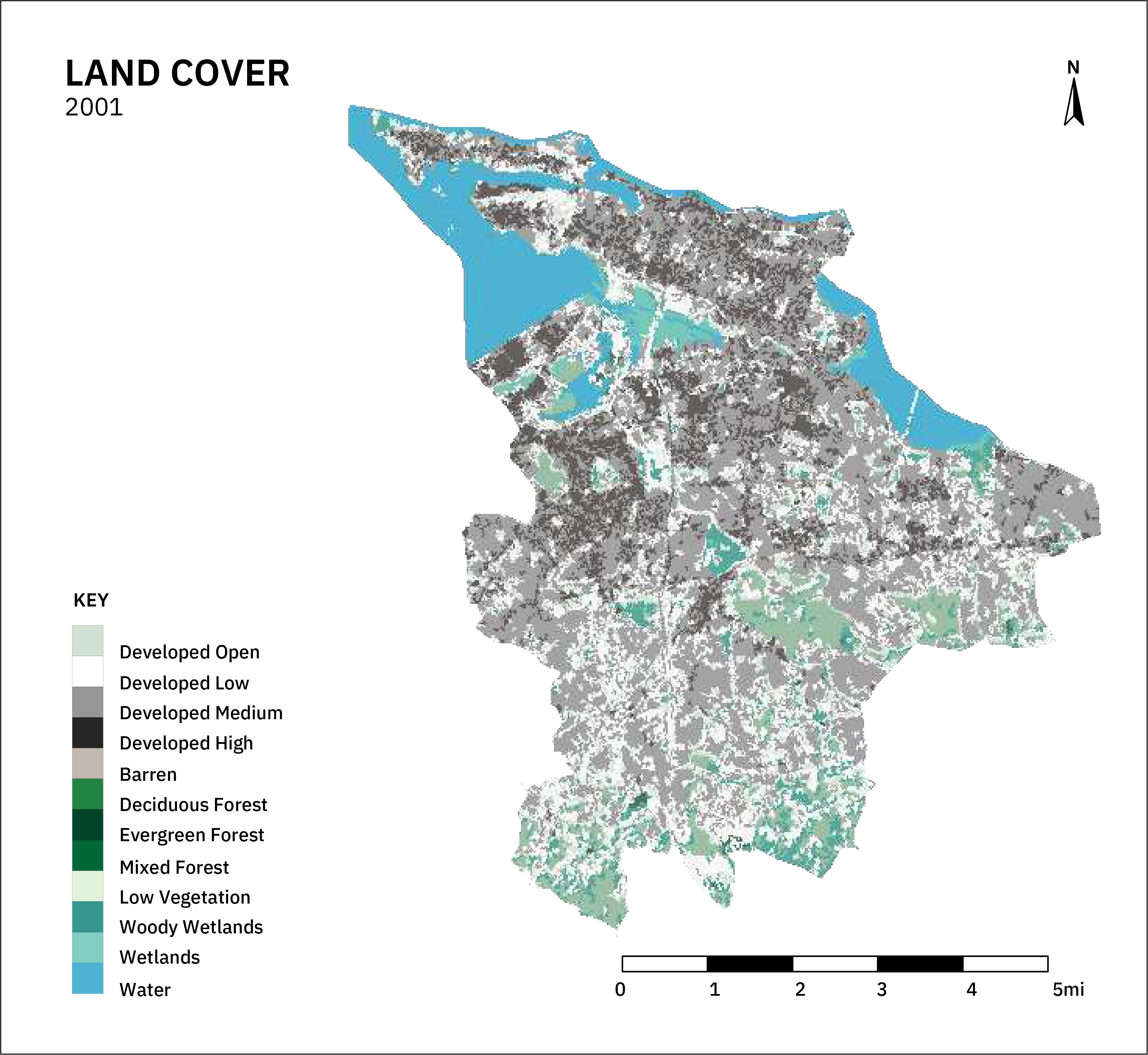

- 6.3 % Forest cover

- Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome

- 5.9% Developed open space

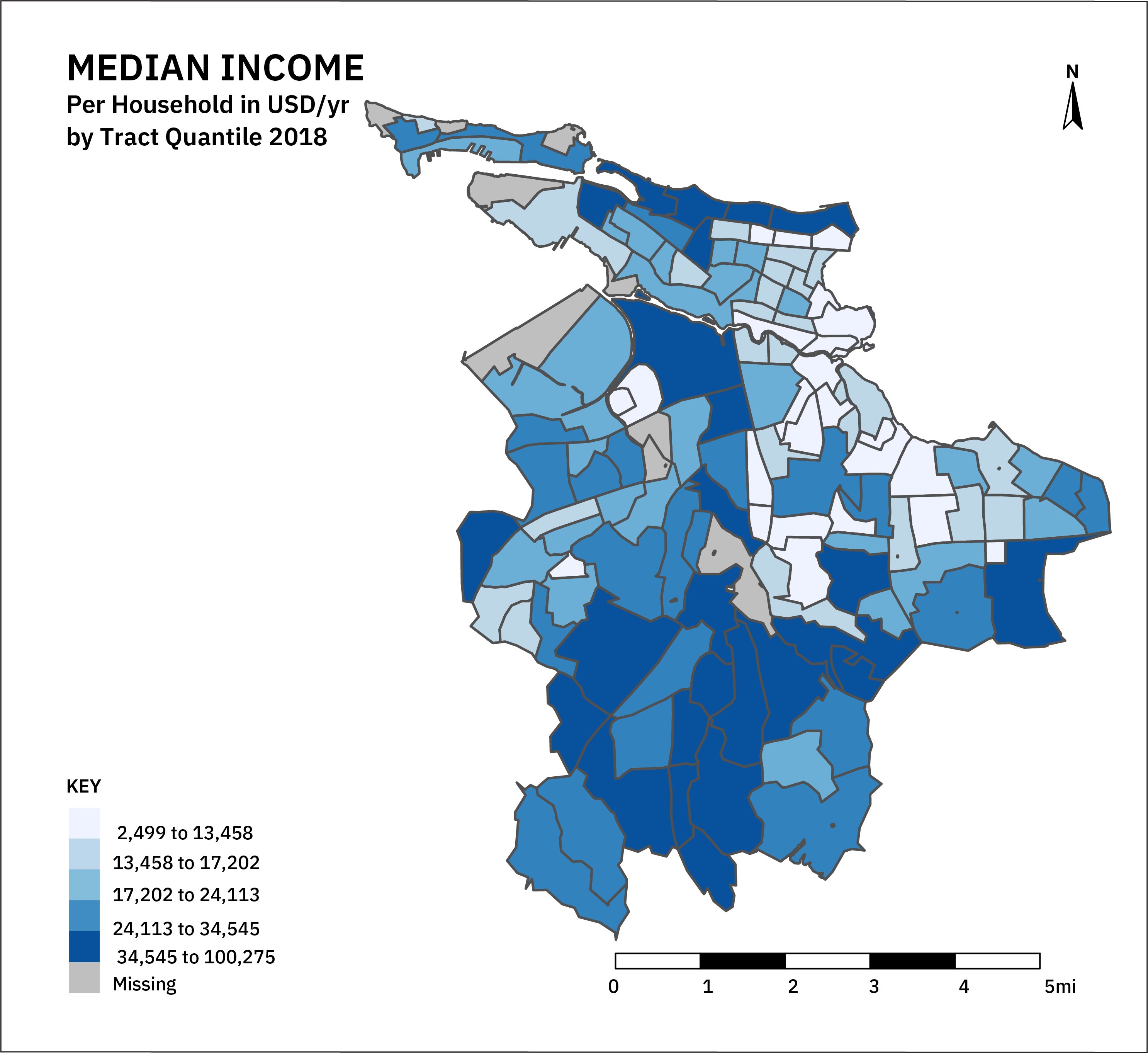

- $21,986 Median household income

- 38.4% Live below federal poverty level

- 68.1% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 24.8% Housing units vacant

- <0.1% Native, 1.5% White, 0.2% Black, 98% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 0.2% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The capital of the colony of Puerto Rico, San Juan’s legacy and present realities cannot be separated from the forcible extermination of Taino people during Spanish colonial conquests, subsequent legacies of mass importation of enslaved Africans, its military occupation by the United States, and generations of state-sanctioned repression under extractive economic systems. These dynamics have produced an intensely segregated city with some of the lowest per capita incomes in the United States.

Enforced poverty takes place amidst a backdrop of tropical bounty and turbulent weather. Climate change and hurricanes have subjected the city to extreme weather events and flooding, and the city has yet to fully recover from the impacts of the 2017 hurricanes Maria and Irma. Like much of the island, the city’s infrastructure systems were hit particularly hard, and recovery has been hampered by its colonial relationship with the United States.

Green Infrastructure in San Juan

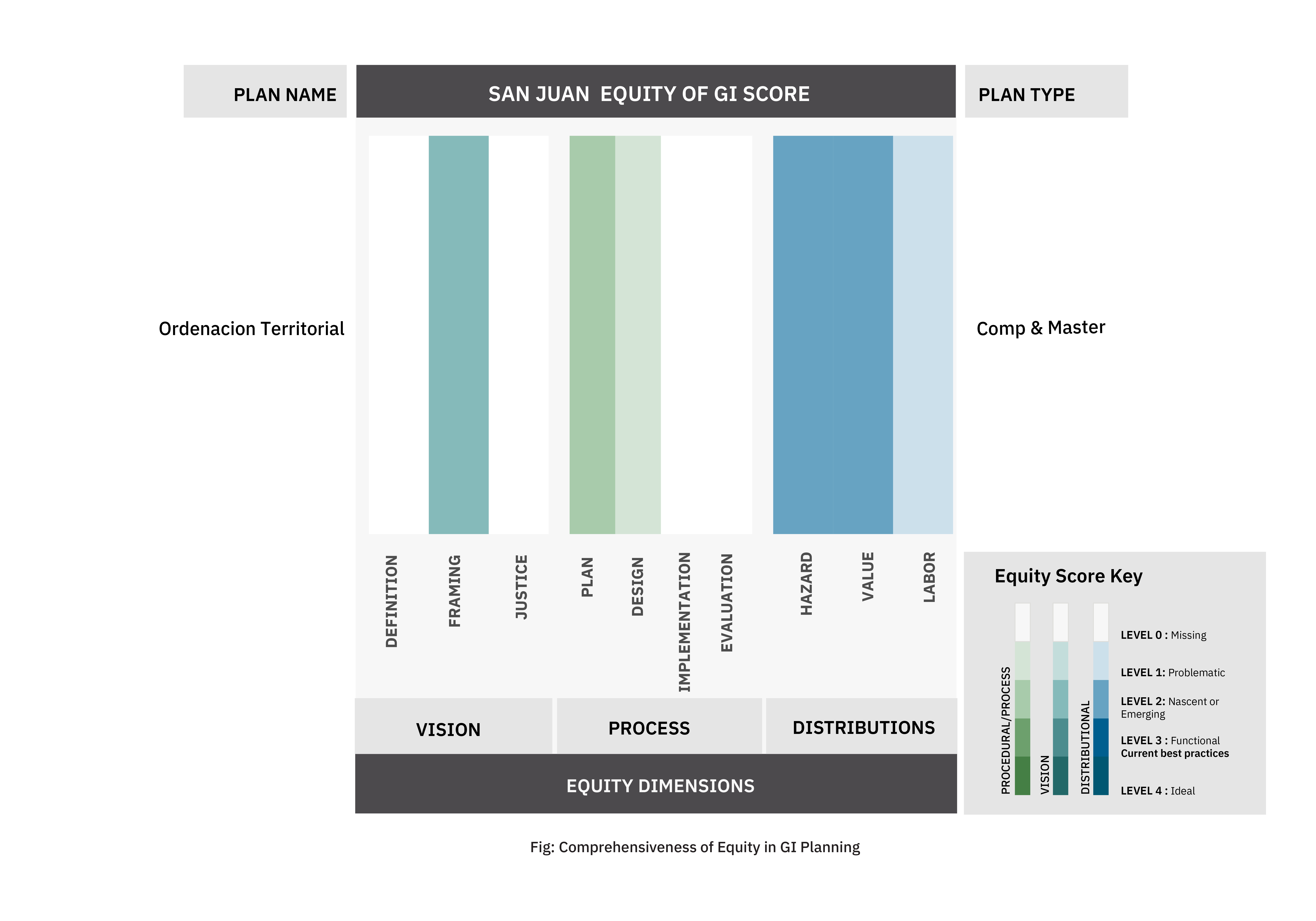

The only plan referencing green infrastructure (Infraestructura Verde in Spanish) was the Plan Ordenacion Territorial or the City Wide Master Plan. In it, the primary benefit of realizing GI functions was to provide ecological habitat.

The plan introduces the GI concept in reference to the Rio Piedras river corridor bisecting the city while connecting coastal and mountain ecosystems. The plan refers to the river corridor as an ecological system, but omits its terrestrial connections, focusing on the river channels themselves. The functions of the river corridor as GI are restricted to its role in improving water quality and ecological connectivity. This idea relates to the landscape concept but does not fit neatly within it.

Key Findings

San Juan’s lone GI plan referenced the need to consider equity but did not define it and there were no mentions of justice. Public participation appeared limited to the initial planning stages with limited means of inclusion in design. Distributional equity was considered somewhat robustly for environmental hazards, quality of urban life, and the role of labor in shaping the urban fabric but these goals were not strongly linked to the city’s green infrastructure system.

100%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

0%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

0%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

San Juan Through Maps

San Juan is a predominantly Latinx city, with significant Native roots falling outside US census categorizations. Significant open spaces can be found throughout the city, the southern low-density suburbs have considerably more access to dispersed green spaces. The city has strikingly large disparities in income and rent burden. Vacancy rates are split between areas being developed for upscale and seasonal rentals and neighborhoods that have faced significant disinvestment.

How does San Juan account for Equity in GI Planning?

Equity and justice do not feature prominently in San Juan’s Comprehensive Plan. While the plan frames several equity concerns around overall urban quality of life and labor market transitions, GI is not connected to these other equity-focused planning efforts. Procedures for involving communities are generally lacking.

Envisioning Equity

San Juan’s GI plan does not extensively discuss equity issues despite some use of the concept in framing its overall goals of improving the quality of public services and urban quality of life. Justice is not addressed.

Procedural Equity

While the Comprehensive Plan appears to have input from local governments and a wide range of city agencies, it does not appear to be a collaborative process. Instead, the plan focuses on extensive analysis of existing conditions, and proposes interventions in the urban fabric, with the plan serving a coordinating function for local governments making development decisions. The plan mentions the need for contextual design, and acknowledges the influence of colonial architecture in transforming the city, but has no provisions for community leadership in project design, implementation, or evaluation.

Distributional Equity

While San Juan’s GI plan discusses the distribution of environmental hazards, it does not explicitly use GI as a hazard mitigation strategy. The plan’s emphasis on quality of life, cleanliness, and order is weakly integrated with its limited discussion of green infrastructure. And, while the plan discusses the role of labor market transitions in reshaping urban form, it does not tie these urban transitions to the development of the city’s green infrastructure system.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

San Juan faces a number of structural political challenges to its self-determination as a city government. However, the country as a whole has maintained long-running movements for genuine political and economic independence. Despite being omitted from current plans in San Juan, a movement led by academics and researchers has been afoot to formalize and develop a city-wide green infrastructure system. To address these interdependent issues, we offer several recommendations on how the city could develop an equitable green infrastructure system.

Community Groups

San Juan has several movements working to achieve climate justice which will require a deep transformation of existing grey infrastructure systems and the elaboration of a city-wide green infrastructure system. One organization within the larger movement, Estuario, focuses on a landscape-level ecological planning concept and has led afforestation and reforestation efforts within the city and beyond. Additionally, some researchers have found that GI has long been autonomously maintained and expanded by residents for aesthetics and food production. There remains a need to evolve GI so that it’s treated as part of the city’s critical infrastructure systems, and to center the needs of communities that have been made most vulnerable to climate-related hazards and extractive economic systems.

1. Develop Contextual Practices for Community-led Planning

San Juan GI plans have no robust mechanisms for community involvement. While participation is not a panacea, grassroots organizations can model and pilot community-led planning and budgeting efforts to rebuild the communities most impacted by recent hurricanes who also face the greatest future risks.

2. Define Equity and Justice in the context of San Juan’s planning

Boricuas have made global headlines advocating for justice in government. This active and forceful discourse has yet to translate into meaningful transformations of urban planning systems in San Juan. Community groups should push for relevant definitions of equity and justice to reframe planning needs, including meaningful community involvement and leadership.

Policy Makers & Planners

Green infrastructure planning in San Juan is relatively undeveloped despite the city’s tradition of parks and open space planning, and more recent efforts to center climate resilience in the city’s infrastructure systems. Policy makers and planners must elaborate the meaning of GI in ongoing city planning efforts and create real mechanisms for addressing community concerns around equity and justice.

1. Build GI as a System

Focusing on the linear corridors of the Rio Piedras systems is an excellent start for articulating a city-wide system of green infrastructure. Formalizing a city-wide vision for GI, that accounts for the diverse types of municipal and private green spaces, will be required to have a cohesive system that addresses the city’s rising climate challenges.

2. GI as Part of the Infrastructure Economy

San Juan’s struggles with climate resilience cannot be separated from its larger challenges with critical infrastructure vulnerability to climate change. The city is facing intersecting crises of massive social inequality, climate chaos, and crumbling infrastructure. Addressing these challenges simultaneously can stimulate new economic growth, and as the Comprehensive Plan notes, investing in labor market restructuring can have lasting impacts on urban form, and vice versa. Investing in the city’s infrastructure systems, including green infrastructure, and prioritizing local firms and high-wage labor, ideally with support from the US Federal government, can address those interlocking challenges.

Foundations and Funders

Foundations and funders already play an important role in elaborating visions and data that shed insight on San Juan’s climate challenges and emergent green infrastructure system. However, with the lack of a formal GI planning framework, ideas and information can only inspire voluntary and piecemeal efforts. There remains a need to invest in community-led planning efforts and to create working models for multi-scalar GI planning within the city. To that end, we provide one key recommendation for philanthropic organizations working in the city.

- Supporting Community Organizing for Intersectional Environmental Justice

As noted above, environmental justice movements, often grounded in life and death struggles for community well-being, have been engines of social, environmental, and infrastructural transformation in San Juan. Foundations and funders can prioritize these grassroots initiatives so that community capacity to advocate for structural change continues to grow and to build community-based institutions and planning processes that can lead to necessary systemic transformations.

Closing Insights

Despite vibrant social movements and efforts to grapple with rising climate challenges, current GI planning in San Juan has a long way to go to be able to address the city’s interlocking challenges of colonialism, entrenched poverty, inequality, and crumbling infrastructure. These great challenges come with great opportunities to build community planning capacity and to elaborate a genuine and grounded vision for what equity and justice mean in the city.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.