SACRAMENTO

Incorporated 1859

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 99.9 sq. miles

- 495,011 Total population

- 5,060 People per sq. mile

- 0 % Forest cover

- Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome

- 14.8% Developed open space

- $58,456 Median household income

- 13.6% Live below federal poverty level

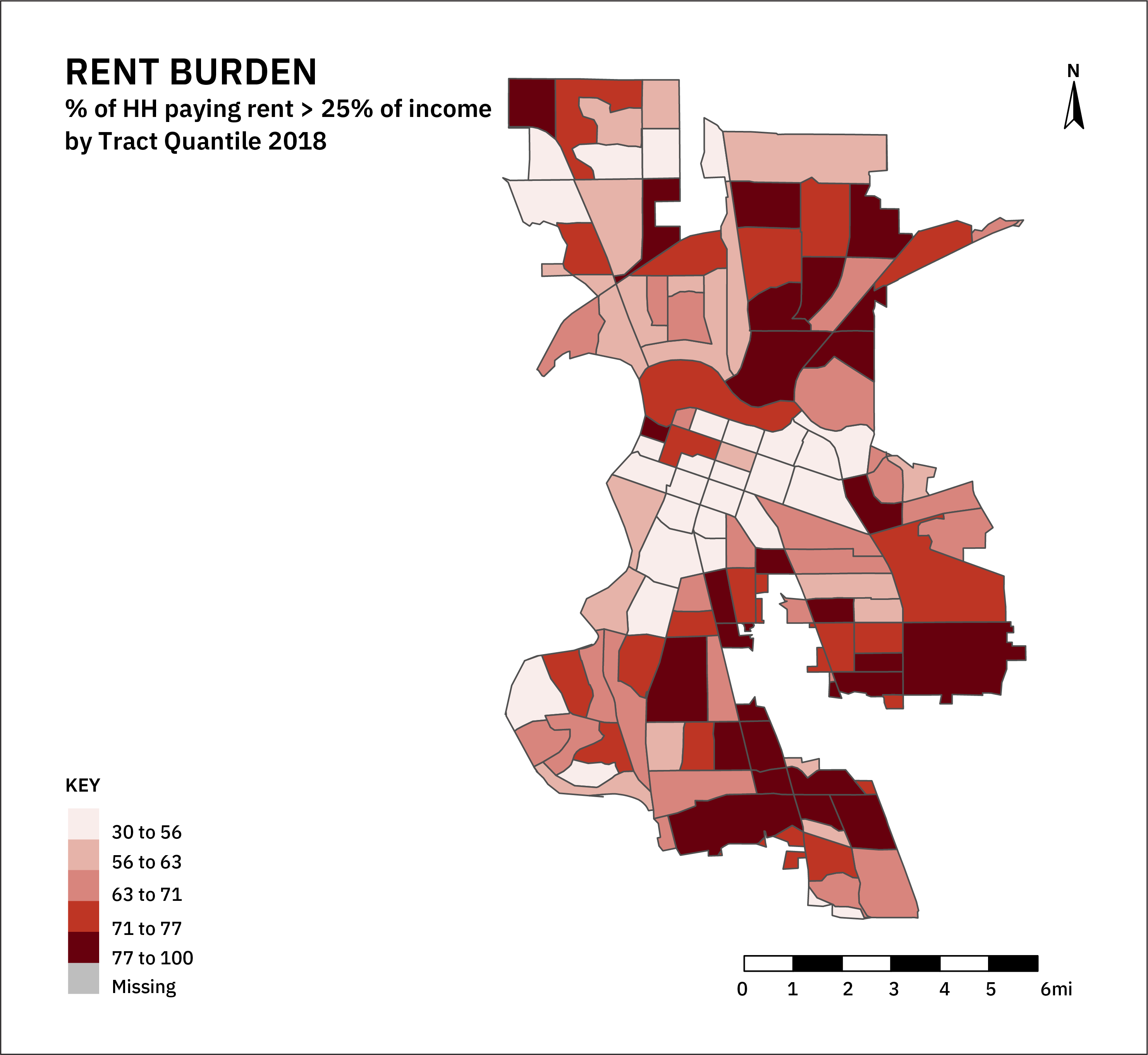

- 64.7% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 6.5% Housing units vacant

- 0.4% Native, 32.4% White, 12.7% Black, 28.9% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 18.6% Asian, 1.7% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The Golden State’s Capital, Sacramento carries a legacy of organizing genocidal exterminations of Native Peoples throughout California and occupies the unceded homelands of the Miwok peoples. The forced removal and state-sponsored murder of Native Peoples intensified when the United States coercively claimed the territory of California after the Mexican-American War and fostered the gold rush. Like with other western cities, the city became a destination for agricultural refugees in the Dust Bowl era, and massive, diverse migrations in the 20th century. Despite this diversity, the city remains intensely segregated along racial lines, mirroring issues in the statewide prison system.

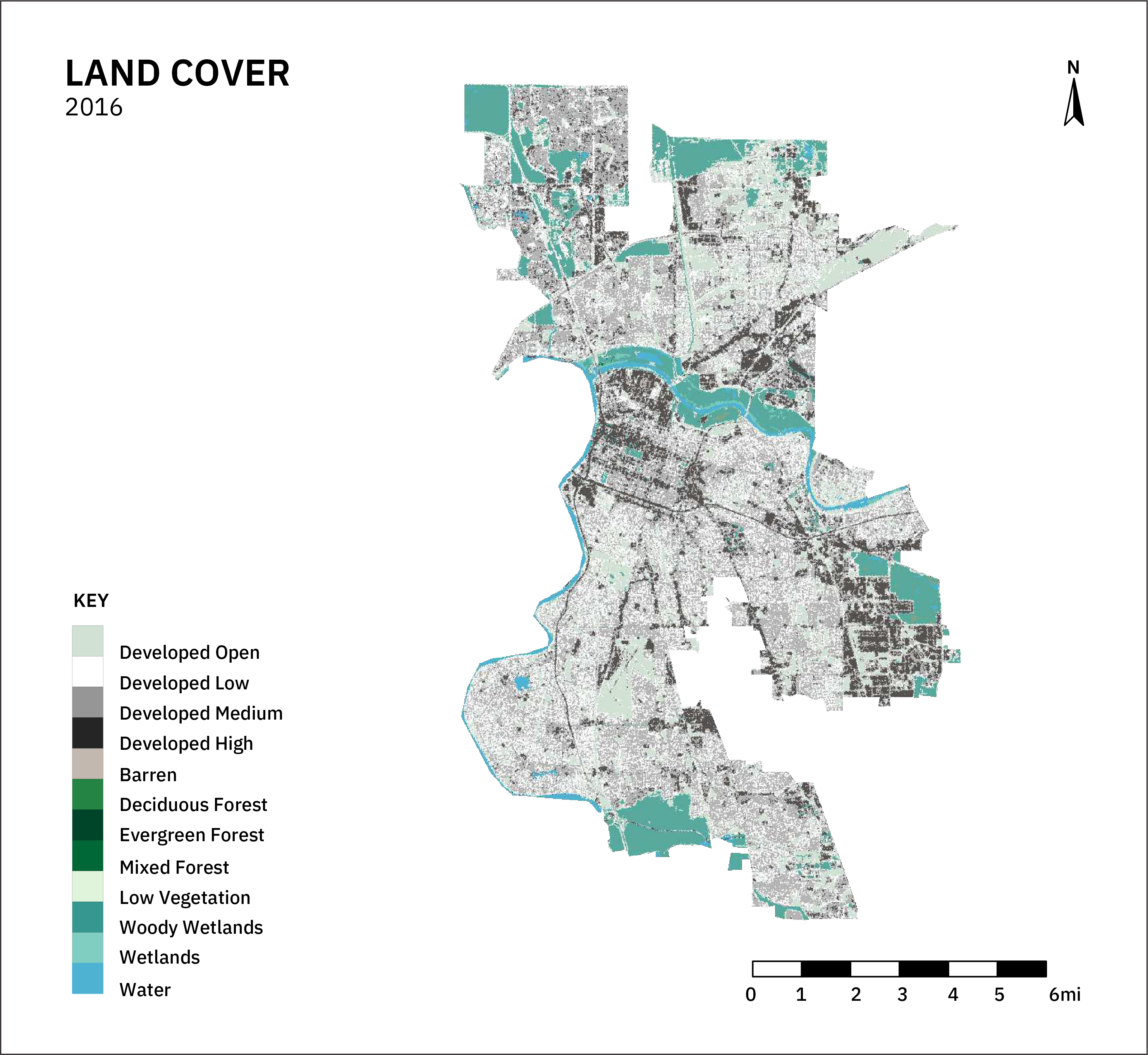

At the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers, the city inhabits a rich riverine ecosystem within California’s Central Valley, draining into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a famously endangered estuarine ecosystem. Increasing climate change-related challenges of droughts, fires, and heatwaves compound long-term environmental change caused by the basin-wide industrialization of agriculture and massive hydraulic infrastructures. Climate-related fires and exploding real estate markets have created a statewide housing crisis.

Green Infrastructure in Sacramento

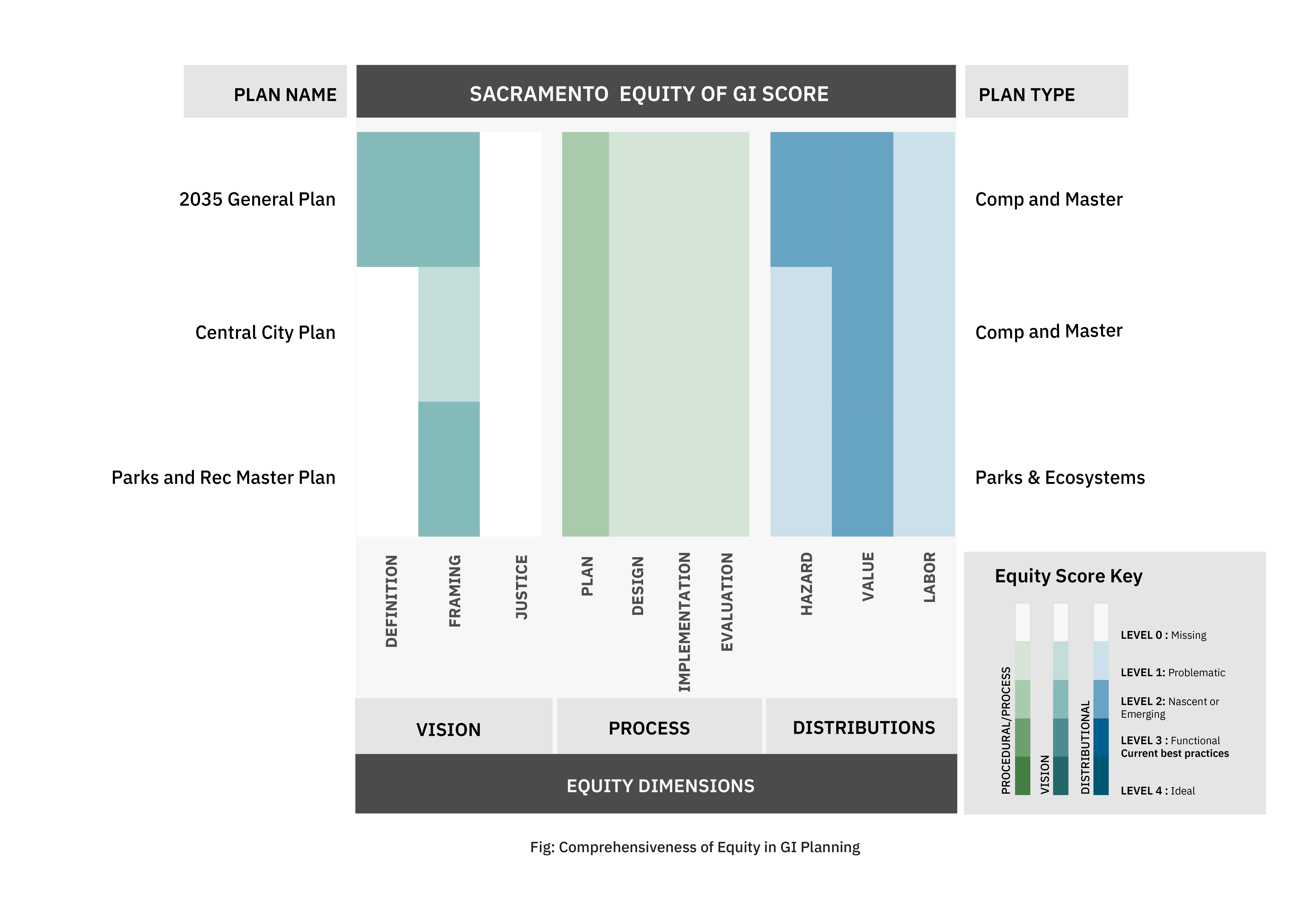

Sacramento plans for green infrastructure through its 2035 General Plan, The City Parks and Recreation Plan, and The Central City Specific Plan (CCSP). The latter plan does not define GI, the Parks and Recreation Plan focuses on a city-wide parks system using a landscape concept, and the General Plan defines both the need for a city-wide network of green spaces and a system of green stormwater infrastructure using landscape and stormwater concepts without appearing to integrate them.

Since the Comprehensive Plan uses both stormwater and landscape concepts, it contains the majority of types of GI, consisting of hybrid facilities and ecosystem elements. It is notable that Sacramento does not explicitly refer to bioswales and green roofs but includes parks, trails, and blue-green networks in addition to general mentions of stormwater management features.

Sacramento GI is managed so that it provides environmental functions, focusing on general stormwater management. The benefits of GI in Sacramento planning are more diverse, focusing on the environmental and socio-economic advantages of good water quality, recreation, livability, community building, education opportunities, and psychological well-being among others.

Key Findings

Sacramento GI plans use the language of equity but rarely define it. They are also uniquely consistent, but not robust, in their mechanisms of public engagement. Plans should do more to address inequities in GI hazards and labor needs, and grapple with the contextual nature of GI’s value.

100%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

33%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

33%

define equity

0%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

33%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Sacramento through Maps

Sacramento sits on a biologically rich confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers. The city is ethnically diverse and highly racially segregated. These patterns are reflected in a patchy and uneven distribution of incomes and rent burden around the city. A polycentric pattern of density contrasts sharply with high vacancy rates in the urban core. Green spaces are unevenly distributed around the city and are dominated by larger parcels of parks and river corridors.

How Does Sacramento Account for Equity in GI Planning?

GI plans in Sacramento consistently use the word equity in relation to the intended impacts of GI, yet only the 2035 General Plan defines it, using a universalist concept of fair access to goods as well as participation in public planning for the future. Framings of equity are more problematic as they do not address the historical causes of injustice or the needs of current residents; instead, they focus on attracting new residents. Plans are silent on justice.

Procedurally, Sacramento GI plans are consistent about including residents in the early stages of planning. This inclusion appears to be driven by state-level regulations around public participation in public planning processes. Participatory mechanisms do not carry over into the design, implementation, or evaluation of GI policies and projects.

Sacramento plans emphasize using GI to universally increase the livability of neighborhoods. To some extent, climate-related hazards are examined contextually in the 2035 General Plan but are more weakly considered than the values of GI. GI labor needs and issues are barely discussed, with current allocations of city resources favoring developers. Marginalized communities are expected to steward GI, including the provision of volunteer labor to aid police in reducing crime in city parks.

Envisioning Equity

Green infrastructure in Sacramento is a key component of the city’s vision to be ‘the most livable city in America.’ These aspirations are framed with no discussion of redressing prior harms from city planning and policy. Most problematically, plans aspire to target ‘slums’ and ‘blighted’ areas for improvements with nary a word about the deeply problematic history of similar urban renewal initiatives. The Parks Plan includes rhetoric about city investments improving personal development, positive relationships, community engagement, and physical and psychological safety, but does not address why there are disparities in these human attributes in the first place.

Procedural Equity

Despite planning law in California requiring open meetings for public planning processes, much of the 2035 Comprehensive Plan appears to be led by an extended technical process before soliciting any substantive public input. A series of attempts to solicit, incorporate, and share public feedback on the draft plan before its approval by public hearing did not show awareness of, or employ, best practices for participatory methods. The Central City Plan had a similar process as the 2035 Plan, though it was also guided by several volunteer advisory commissions. The composition of those commissions privileged developer and landowner interests and not those who would be most affected by the planning decisions. There were no substantive mechanisms for including affected communities in the design, implementation, or evaluation of GI.

Distributional Equity

Sacramento GI plans do not robustly consider the distributional dimension of equity. While the 2035 General Plan identifies and includes a diverse set of intersecting hazards to be managed with GI, it does not grapple with their social distributions, how some communities have been made more vulnerable than others, or the potential unintended consequences of the city’s approach towards hazard management. While the CCSP focuses on reducing flood hazards in the central business district, it does not discuss how pre-existing and current flood infrastructure entrench flood vulnerability. Most strangely, it discusses urban renewal projects without discussing the hazards of displacement caused by current planning efforts. Both the General Plan and Parks Plan rely on volunteerism for GI stewardship, with the Parks Plan explicitly calling for communities to collaborate with police to increase park safety, rather than discussing or addressing the underlying social conditions causing a need for police, or any sort of community-based alternatives.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

As a member of the Government Alliance on Race and Equity, Sacramento seeks to address equity issues through urban planning. However, the city’s current GI plans, two of which have a much larger scope than only GI, appear to entrench the problems caused by prior planning efforts. They will likely replicate the atrocities of previous urban renewal efforts, accelerating displacement in minoritized and marginalized communities. While equity in planning must be defined by those impacted by plans, we provide several recommendations to improve the equity of current planning efforts.

Community Groups

Many community groups working on racial and economic justice in Sacramento do not appear to be represented in current GI plans. This exclusion is concerning, given California mandates for public participation in planning. The early stages of more open participation often devolve to a model of advisory boards that are disproportionately staffed by development interests. In the long-term, these issues can only be addressed through structural transformation of city-level decision-making and policy. Community groups, however, appear to have several key areas where their influence could address inequities in current GI plans.

1. Embed Equity within City Planning

The current Government Alliance on Racial Equity-led city initiatives are certainly a step in the right direction, and the creation of a specific equity plan for the city will hopefully improve processes for addressing racial and environmental justice and their outcomes. However, current plans and decision-making systems stand to reinforce ongoing inequities. Community groups can and should advocate for transformed planning processes that give equal if not greater weight to community voices and that represent renters and other marginalized groups.

2. From Model Projects to Model Plans

The organization Environmental Justice Coalition for Water (EJCW) has led a model stream restoration project on Morrison Creek in South Sacramento. Such projects showcase how communities can effectively collaborate with state and city agencies and each other to dramatically improve environmental conditions on the ground. These types of initiatives would be even more successful, and much less likely to lead to housing displacement if they were undertaken city-wide. Community groups can and should advocate for current planning initiatives to be led by coalitions of community groups themselves.

3. Address Equity and Justice

Given the history of organizing for racial justice in California and Sacramento, it is inexcusable that city plans do not acknowledge historical or current justice issues.

City plans should explicitly define equity and justice in their appropriate contexts. Communities harmed by past and present city policies and plans must be the ones who define those terms, along with the potential conditions of repair and the transformations required, so those harms are never experienced again. Community groups can take the lead on defining equity and justice to shape the application of current planning efforts, as well as emergent city initiatives.

Policy Makers & Planners

Current plans have made some attempts to address deep-seated equity and injustice issues in Sacramento. However, plans could go much further in defining equity and justice – beyond the minimum statewide standards of consultation. Plans should get serious about addressing climate hazards, and should focus on creating well-paying jobs to build community wealth.

1. Define Equity and Justice

The city has committed to a 5-year equity plan by participating in the GARE initiative described above. However, city agencies should go further in having operational definitions of equity and justice in the specific context of Sacramento’s troubled racial history and present. Utilizing the framework we provide through this project, these terms must address genocidal dispossessions of land from Native Nations, along with the myriad of other injustices experienced by minoritized communities throughout Sacramento’s history and present. Drawing upon the lived experience of Sacramento communities, these definitions should be embedded within, and shape, city plans and policies.

2. Go Beyond Minimum Standards of Consultation - Embed Within the Lifecycle

The city can choose to go beyond the statewide standards for public participation and be a leader in showing what public inclusion means in land use planning. Using the framework we provide in this project, consultation would include specified processes for centering community experiences and giving communities real power during the design, implementation, and evaluation of planned activities.

3. Get Serious About Climate-related Hazards

It is concerning that the numerous climate-related hazards unevenly impacting Sacramento communities are not robustly analyzed by current green infrastructure plans. These multidimensional hazards, including heat waves, droughts, extreme weather, and flooding, should be analyzed with respect to how certain communities have been made more vulnerable than others. That these analyses are not being conducted and contributing to the framing of the distributional dimensions of GI’s equity in the city is another point to be remedied.

4. Real jobs, wealth, and urban vitality

Requiring community members to conduct GI maintenance and policing in Sacramento is highly problematic, akin to asking marginalized communities to facilitate their own displacement and enable greater violence against themselves. City policies and plans could instead focus on transferring wealth to marginalized communities through alternative models of community-led design and implementation and skill-building. Further, in the spirit of restorative justice, they could invest in alternatives to policing green spaces, and instead focus on supporting community cohesion through anti-displacement efforts and investments in underlying public services.

Foundations and Funders

Foundations and funders can play an important role in improving the equity of green infrastructure planning in Sacramento. To address the massive omission of critical and community points of view in shaping Sacramento’s GI planning processes, foundations and funders can support community organizations advocating for planning transformation and working on broadening participation in existing processes. Funders can also provide material support for initiatives that simultaneously address housing and environmental justice.

1. Broadening and Deepening Participation

Sacramento plans highlight major shortcomings in the operationalization of statewide policies and mandates for public participation in land use planning at the municipal level. The plans examined have minimal inclusion, with meeting times and locations that likely severely limit participation of impacted communities. These shortcomings in the initial stages of planning continue through project design, implementation, and evaluation. There is an urgent need to evolve the participatory paradigm in California to reflect the lived experience of communities affected by land use planning.

2. Advocating for Transformation

Sacramento must transform both its urban form and its decision-making systems to deal with the connected challenges of housing insecurity, massive income inequality, and environmental and climate justice issues. This could be accomplished by developing labor initiatives that use this urban transformation to build wealth in marginalized communities. The national need for large-scale municipal reinvestment in social and physical infrastructure is especially poignant in cities like Sacramento where disparities are so stark.

3. Providing Material Support for Housing and Environmental Justice

Since existing planning systems are highly problematic in terms of how they address the equity of GI, there is an urgent need to implement new planning mechanisms to meet community needs. There is certainly a need to evolve state and city policy to be genuinely participatory on the terms of impacted communities. There can and should be an equal emphasis on transforming models of community-based ownership of green infrastructure and other assets, including housing.

Closing Insights

Equitable green infrastructure in Sacramento requires a transformation of existing planning systems, a critical look at the relationship between housing precarity and green infrastructure investments, and the strengthening of state and municipal level mandates for plans to address historical and ongoing justice issues. With an energized and supportive civil society, policy makers and planners can enact meaningful shifts today for a greener and more equitable future.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.