SYRACUSE

Incorporated 1825

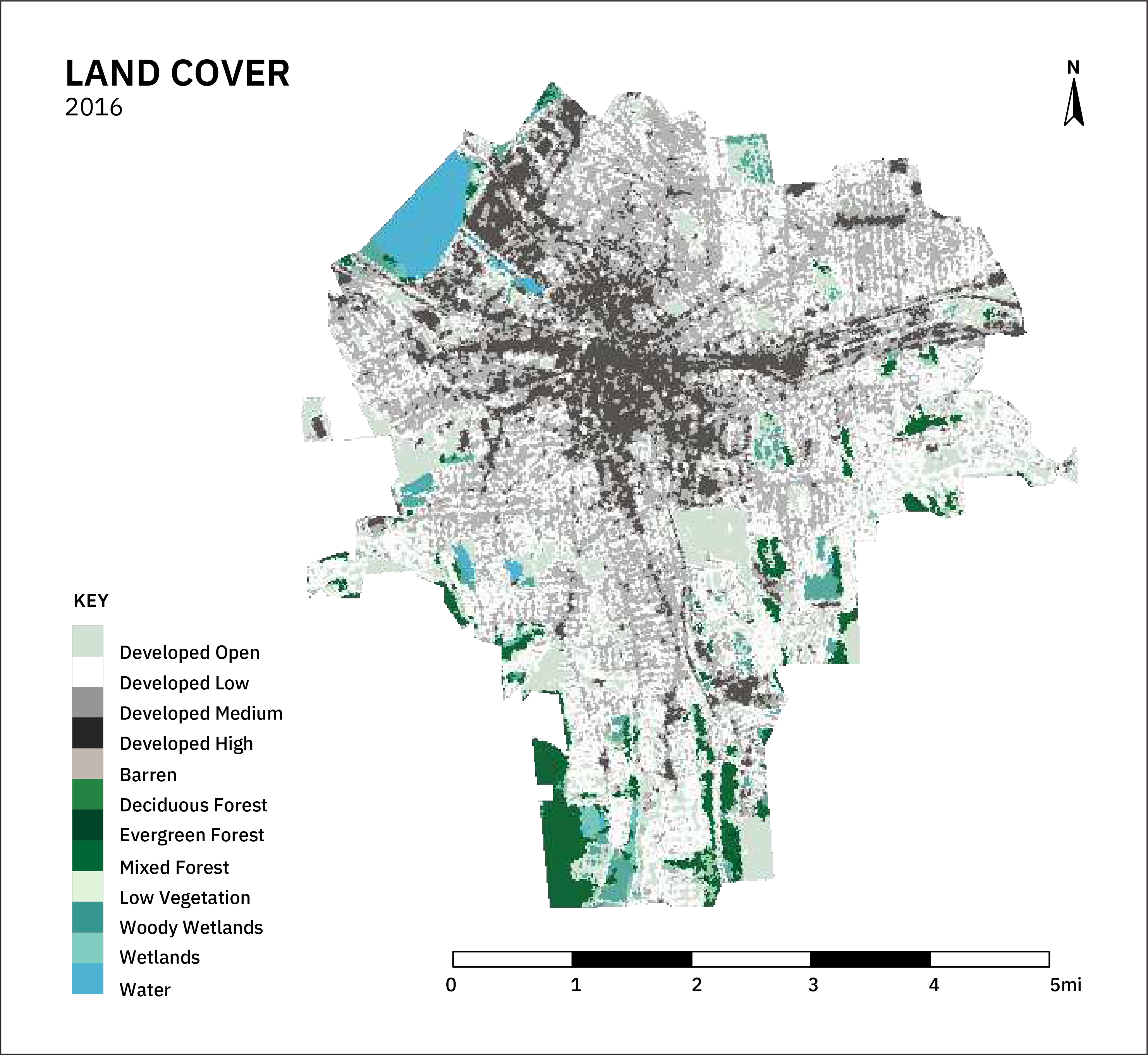

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 25.6 sq. miles

- 143,293 Total population

- 5,725 People per sq. mile

- 5.6% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 13.2% Developed open space

- $36,308 Median household income

- 24.4% Live below federal poverty level

- 65.4% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 17.8% Housing units vacant

- 0.9% Native, 50% White, 28.5% Black, 9.4% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 6.5% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

Syracuse occupies the homelands of the Onondaga Nation, members of the Haudenosaunee confederacy, who maintain their traditional government while confronting the dynamics of colonialism in the region. The city has steadily grown throughout its history, though the population has been stable for the last decade.

Residents in the intensely segregated city have long fought for environmental justice. De-industrialization profoundly impacts the city’s labor markets, while ecological restoration and highway removal promise to reshape the city’s future. Climate change threatens the city with heat waves, increased flooding, and the possibility of prolonged drought.

Green Infrastructure in Syracuse

Syracuse GI plans examined included its current Comprehensive, Land Use, and Sustainability Plans. Like several other cities examined, Syracuse GI deals only with stormwater management, and the city itself has limited influence on the Onondaga County Department of Water Environment Protection’s regulated storm and sewer programs (which fall outside the scope of this analysis). The city has long supported the County’s ‘Save the Rain Program’ with its Sustainability, Comprehensive, and Land Use Plans which we examined for this project.

These GI plans focus on disconnecting impervious cover from the city’s combined sewer system using a limited set of hybrid facilities and green technologies, including rain barrels, pervious pavers, bioswales, and green roofs.

Syracuse GI plans describe the benefits of addressing these persistent issues primarily as improving water quality, recreation opportunities, reducing the cost of infrastructure, and improving urban aesthetics.

Key Findings

Only Syracuse’s Sustainability Plan explicitly refers to equity, and even that plan does not define it. All plans examined had some basic mechanisms of inclusion in place, but did not thoroughly consider the causes of inequity and injustice, nor do they make detailed plans to address inequalities in the distribution of hazards and benefits of GI.

33%

explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

67%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

33%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

33%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Syracuse Through Maps

Syracuse has a dense urban core abutting lake Onondaga, with green space unevenly distributed around the urban periphery. Rent burden, income, and vacancy rates are all spatially clustered and appear highly correlated with race.

How Does Syracuse Account for Equity in GI Planning?

Syracuse GI plans are largely silent on equity and justice issues. GI is generally framed as a universal good and as part of a larger program of urban improvement that emphasizes a need for new real estate development. No plan in Syracuse addressed all ten dimensions of equity in our evaluation tool.

Envisioning Equity

A definition of equity was not found in a single Syracuse plan. The Comprehensive Plan describes a vision for the city that has equity implications but does not focus on equitable development. The Sustainability Plan states that social equity is a major goal, but focuses on economic development and improving urban quality of life without engaging in questions of current inequities. The Sustainability Plan also referred to the need to address food justice but a stormwater-focused GI concept was seen as potentially competing with urban agriculture for space, rather than complementary to an urban food system concept.

Overall, no plans examined current inequalities or disparities in the city. They framed persistent issues of poverty and unemployment as resolvable by attracting new markets for real estate development alongside investments in schools.

Procedural Equity

The city’s GI plans have some basic mechanisms of inclusion in plan formation, although implementation and evaluation are generally problematic. Inclusion in planning is generally limited to meetings and steering committees composed largely of local experts and city agencies. There is limited documentation of public comments, or how and why individuals were appointed to steering committees. No effort appears to have been made to include those disproportionately and negatively impacted by previous planning decisions. The Comprehensive Plan states that the city neighborhood planning initiative, Tomorrow’s Neighborhoods Today, will have committees that reflect the needs of individual neighborhoods; however, it does not describe a process to achieve such representativeness.

Design-wise, there are some avenues identified for community involvement in zoning and smaller-scale planning but there are no participatory design processes described. Similarly, plan implementation is largely a process run by city agency professionals, with no clear avenue for public participation. The Comprehensive Plan will be reevaluated as part of the update process but it is not clear if this will include an evaluation of the impacts of GI on affected communities. Similarly, the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) premiums described within the Land Use Plan, a major vehicle for GI implementation in the city, will be internally evaluated by city agencies for their effectiveness. The Sustainability Plan was alone in describing some type of community-based evaluation. However, it does not explicitly involve the community in evaluating plan effectiveness and only makes vague commitments to a ‘reputable’ community sustainability rating system.

Distributional Equity

Syracuse GI plans do not have a robust discussion of managing multiple hazards with GI, although there are some mentions of addressing more than one hazard at the same time. For example, the Comprehensive Plan discusses the need to improve traffic safety at schools by integrating GI into streetscape design. And while the Sustainability Plan discusses managing stormwater runoff, mitigating the urban heat island, and addressing traffic safety all at the same time, there is no analysis or discussion of the distribution of these hazards or how some communities have been made more vulnerable to them than others. The Land Use Plan discusses some legacy contamination issues in relation to GI, yet neglects any examination of their social or spatial patterns. All Syracuse GI plans use broadly similar language around quality of life and reversing urban decline. Yet they do not acknowledge the contextual nature of the value and hazards that may accompany redevelopment such as displacement and gentrification, nor the unevenness in the distribution of GI value.

The Sustainability Plan describes a need to install GI with incentive programs for property owners. This would provide some limited distribution of financial benefits in exchange for homeownership. Otherwise, Syracuse GI plans are silent on labor issues.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

GI planning in Syracuse has a long way to go to address the city’s issues of entrenched poverty, segregation, and environmental injustice. While GI may partially address longer-running environmental justice concerns of the city’s combined sewer overflows, ongoing work seeks to understand how the benefits of GI intersect with uneven social vulnerability in the city. As the city seeks to reinvent itself through highway removal and ongoing ecological restoration programs, debate continues about how to prevent housing displacement during the current wave of reinvestment. Here we provide several concrete recommendations for how future GI planning can evolve to address equity issues.

Community Groups

Syracuse’s grassroots community groups have been fighting for racial and environmental justice for a long time. These groups have the place-based knowledge to determine the current and potential meanings of equity and justice and their experiences must be centered in the evolution of urban planning in the city. Based on our reading of current plans, community experiences can inform two large necessary evolutions of urban planning. These are:

1. The Meaning of Equity and Justice

Current plans do not address equity or justice explicitly. Today, the language of environmental justice is being used to discuss the large-scale redevelopment and highway removal in the urban core, which, if done correctly, presents an opportunity to right historical wrongs. However, plans do not discuss those historical wrongs, or how they continue to shape the present. Community groups should articulate their specific needs and visions for accountability and justice in ways that redistribute power to frame environmental justice issues in the city or else risk their experiences being swept aside in the rush to redevelop.

2. Transforming City Planning to achieve Procedural Equity

Community groups in Syracuse seem largely left out of current planning efforts. While some have called for greater inclusion within urban planning in the city, there are no clear avenues for communities to shape how those planning processes are formed. Drawing upon current best practices, greater outreach at the earliest stages of planning is needed. Also, communities should be provided with the resources to set planning agendas and develop a community-based planning process that serves their needs.

Policy Makers & Planners

Syracuse GI plans are primarily focused on stormwater management despite the city being poised for a major redevelopment project. The city has a historic opportunity to not only address the environmental injustice of I-81 but to restructure the fabric of the city core to meet the needs of residents. To achieve these twin goals, we have three major recommendations for policy makers and planners in the city.

1. Embrace a More Integrative Concept of Green Infrastructure

Employing a more integrated concept of green infrastructure is crucial for Syracuse city planning going forward. This would provide greater coherency and linkages between existing initiatives, and allow for a more comprehensive and engaged GI planning process. The integration of ongoing planning efforts relevant to a city-wide GI system with those focused on stormwater management will more effectively meet stormwater management goals while simultaneously supporting objectives for alternative transit and increased park spaces. Merging stormwater programs with a landscape concept of GI will connect the city’s urban forestry program, tree canopy ordinance, and city-wide open space and trail network schemes with its stormwater management planning.

2. From Professionalization to Participation

GI planning and design within the city and county are largely run by GI professionals and their skills and knowledge are useful. Yet, if expert opinion is all that is considered when planning for and designing GI, then GI will be out of touch with the experiences, needs, and desires of residents. While Syracuse government and planners define the city as a habitat designed for people, they can extend this thinking to characterize the city as a habitat designed by people for people. With this logic in mind, planners can embrace ongoing GI implementation and urban redesign as an opportunity evolve processes that shape environmental justice.

3. Urban Redevelopment That Supports Current Residents

Like many other cities we examined, Syracuse uses its GI programs to attract new real estate investment and growth rather than support residents’ needs and aspirations. The existing residents and businesses are the backbone of any attempt to reinvent a city and incentivizing new development exclusively will lead to their displacement. Elaborating a city-wide GI system presents opportunities to build community wealth in place.

Foundations and Funders

Syracuse’s GI programs already benefit from several foundations and funders undertaking work in the city. These institutions can improve the equity impact of their work in one important way in the city.

- From Funding Distribution Gaps to Building Community Power

Several projects in Syracuse seek to improve green infrastructure by making environmental amenities more widespread and reducing disparities in exposure to managed hazards. These programs, while admirable, fall short of addressing underlying causes of environmental racism; unequal access to political and economic power is a primary driver of inequity in urban systems. Investing in organizations that build community power to transform urban planning processes, so that they are run by the communities they intend to serve, can and should be a major focus of funding efforts within the city. Given that the city sits within the territory of one of the oldest direct democracies in the world - the Haudenosaunee confederacy - it would do well to learn how to operationalize democratic planning drawing upon the systems that cared for the land from time immemorial.

Closing Insights

Despite a decade of leadership on green infrastructure implementation for stormwater management, plans in the City of Syracuse are largely silent on equity issues. Building meaningful processes of community leadership within planning systems remains a major need. Still, the city can address the legacies and realities of environmental and social injustice by implementing a more integrative concept of GI to shape environmental and infrastructure planning efforts, providing the necessary resources for community-led planning, and restoring Indigenous systems of governance.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.