WASHINGTON DC

Incorporated 1790

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 68.4 sq. miles

- 684,498 Total population

- 11,196 People per sq. mile

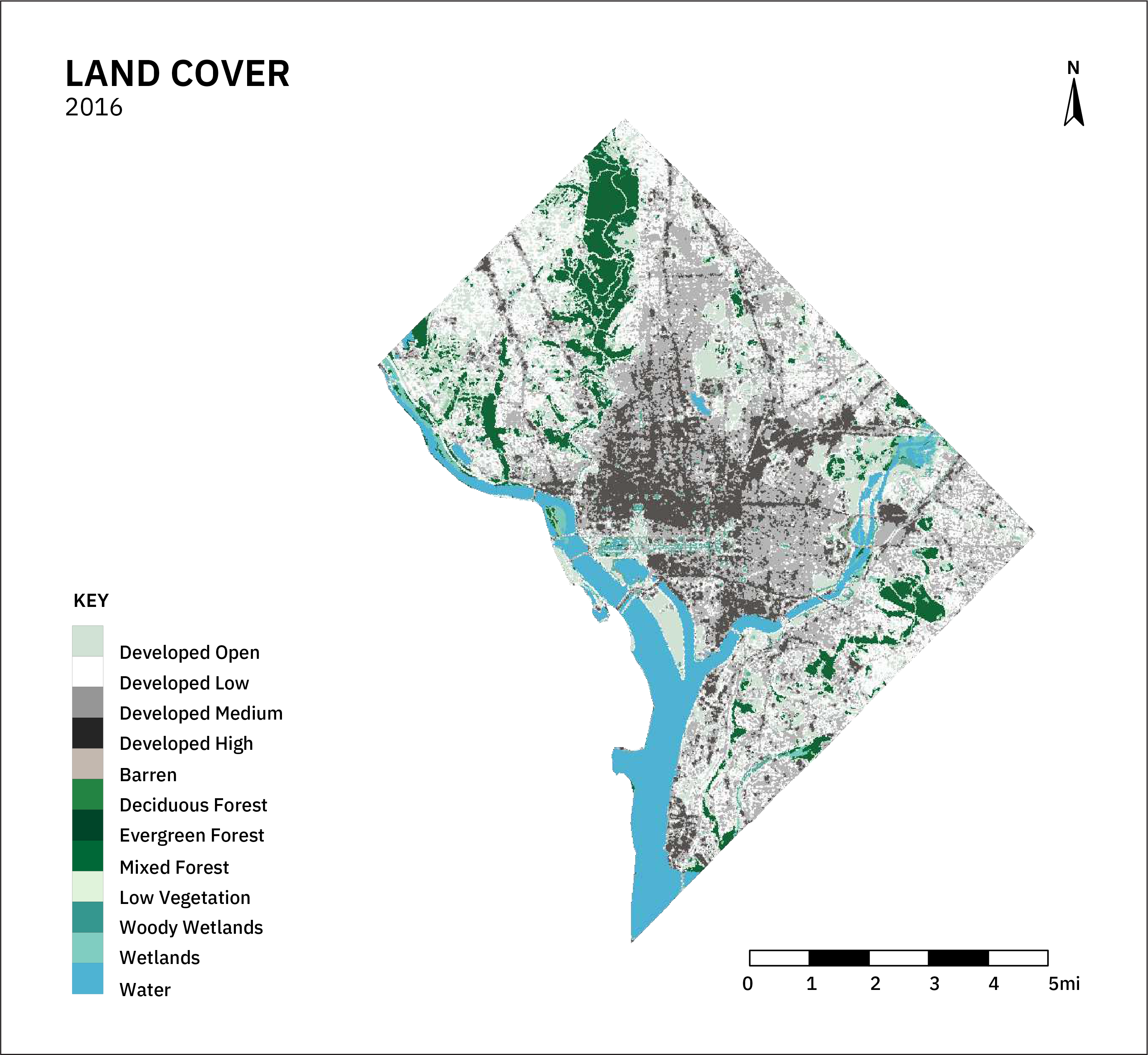

- 9.2% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 15.1% Developed open space

- $82,604 Median household income

- 12.9% Live below federal poverty level

- 59.4% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 9.7% Housing units vacant

- 0.2% Native, 36.6% White, 45.4% Black, 11% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 3.9% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

The Nation’s Capitol occupies the lands of Piscataway and Nacotchtank peoples who have continued to fight for their treaty rights. Since before the Civil War, the city has served as a major center for Black culture and organizing. Waves of growth, uneven investment, and dispossession structure patterns of segregation that are persistent to this day.

The low-lying city occupies the tidal confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia rivers. A hilly landscape surrounds the central city, with clay-rich soils and bedrock ridges creating many small drainages across the city. Like other East Coast cities, rising sea levels, increasingly strong and frequent storms, and heatwaves have collided with record snowfalls to stress the city’s infrastructure systems. Jurisdictional complexity has hampered city efforts to achieve compliance with federal regulations, mirroring persistent patterns of environmental injustice in the city. The city struggles to address housing shortages with the metropolitan area absorbing large amounts of displaced people. Booms in commercial real estate development and rising housing costs drive these patterns, as the city has yet to recover its peak population of over 800,000 residents in 1950.

Green Infrastructure in Washington DC

The majority of GI plans in Washington DC deal with stormwater management, although the city’s combined sewer overflow plan seeks to integrate natural processes into the urban environment. The Anacostia Watershed Restoration Plan focuses on climate resilience with a green infrastructure concept. The city was unique among those examined in having a wildlife-focused plan, which used the terminology of GI without defining it.

Reflecting this range of plans, the city defines a diverse set of GI types spanning ecological elements, hybrid systems, and green technologies. Similarly, plans focus on providing numerous social, environmental, and infrastructural functions with GI. Benefit-wise, city GI plans seek to deliver a diverse range of environmental, socio-economic, and infrastructure system benefits.

Key Findings

GI Plans in Washington DC commonly refer to the need to address equity and justice concerns, and yet equity was defined in only one plan. Procedurally, city plans have few binding mechanisms for equitable design, implementation, and evaluation. The city’s GI programs, however, are widespread and within city-supported redevelopment programs.

100%

explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

11%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

33%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

11%

define equity

0%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

11%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Washington DC Through Maps

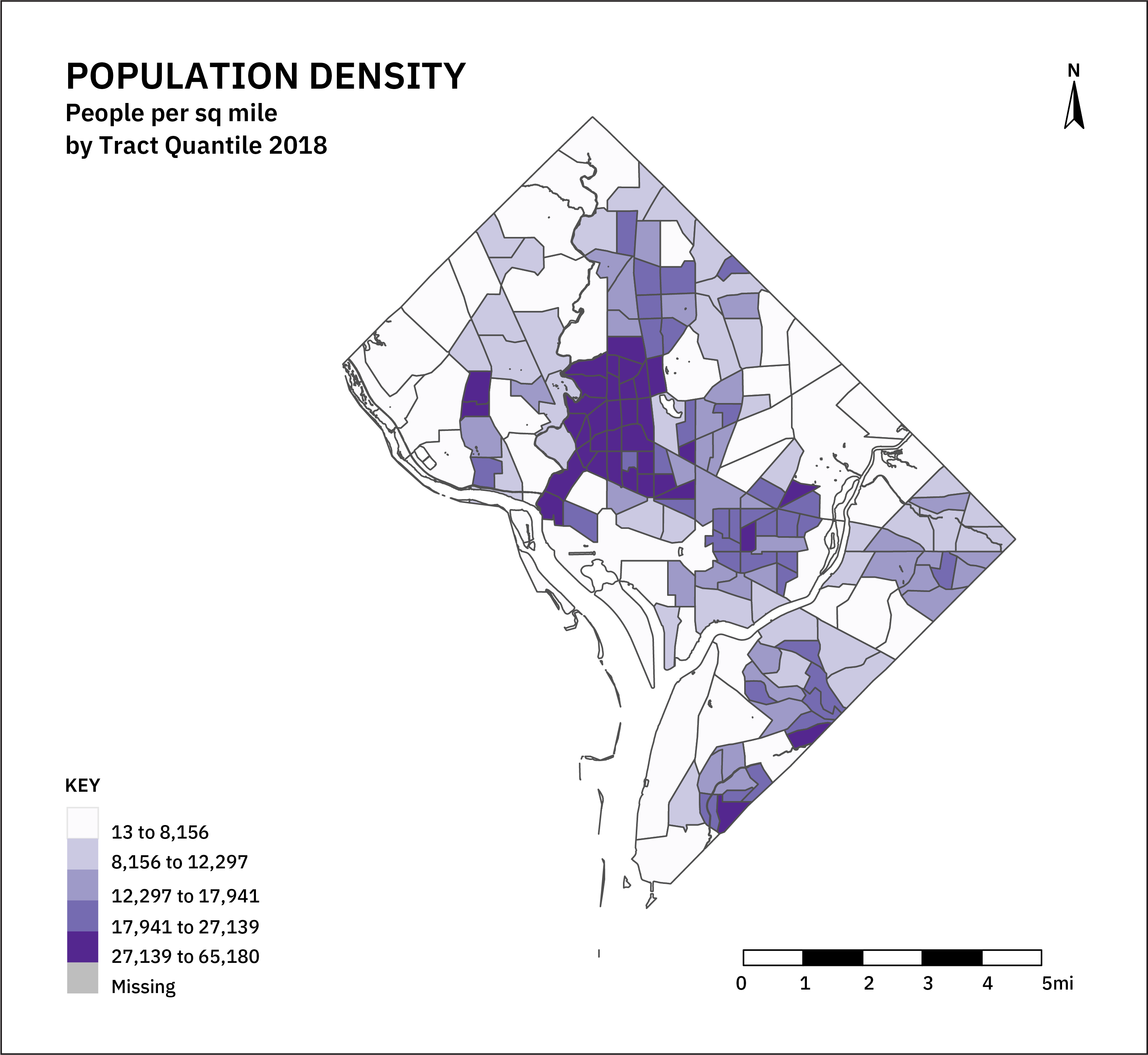

The 8 wards of Washington DC display striking contrasts in their density, infrastructure, and amount of open space. The ‘green wall’ of Rock Creek Park has some of the wealthiest and whitest residents in the northwest portion of the city. Gentrification has displaced many lower-income residents, although the city has strikingly high vacancy rates distributed throughout. A majority of DC residents are rent-burdened, with rates remarkably high in the southeast portion of the city.

How does Washington DC account for Equity in GI Planning?

GI plans in Washington DC weakly frame and define the relationships between green infrastructure, equity, and justice, with only one plan containing a definition of equity. The plans only perfunctorily include communities aside from the most recent Sustainability Plan which appeared to make an effort for widespread outreach. The city’s GI Plan discusses the need for community-based evaluation of city GI programs but does not provide robust mechanisms to do so.

While GI plans seek to mitigate stormwater and flooding hazards, they fail to robustly address multi-dimensional and intersecting issues of climate hazard management with changing property values. While the relationship between evolving GI programs and some forms of labor are explored, they require significant elaboration.

Envisioning Equity

The DC Sustainability Plan is the only document we examined that defines equity, however, it essentially aims for a ‘post-racial’ society without acknowledging structural issues or historical hurdles. This is a type of equity jiu-jitsu that appears unique to the district, as it invokes Title IV of the Civil Rights Act to expressly prohibit providing disproportionate benefit to social groups based on race as a criterion. The current logic framing equity limits consideration of the substantive impacts of GI on stormwater program cost burdens due to the omission of analysis or discussion of historical and current causes of racial inequality in the city and a fairly narrow conceptualization of green infrastructure.

Procedural Equity

The Sustainability Plan again led the way in setting up a relatively large-scale public outreach process, explicitly seeking to include those underrepresented in prior planning processes. However, survey responses seem highly curated and lack documentation of the demographics of participation. This lack, despite the claim of representativeness, especially of underrepresented communities, diminishes the value of the responses. All of the storm and sewer plans complied with federal regulations regarding public meetings and comment periods but did not discuss well-documented issues with community inclusion in such processes. A lack of inclusion carries through to design and implementation.

The evaluation phase in the City’s GI Program Plan (a GI-specific component of the Long Term Control Plan), highlighted some best practices for inclusion, explicitly seeking public feedback on the performance of GI. However, the solicitation of community input was restricted to the stormwater management performance of GI, devised to ensure the appropriate maintenance of facilities rather than assessing the overall social impact of GI installations.

Distributional Equity

The distributional equity of GI in the city was not vigorously addressed in any DC plans. While plans contained a range of benefits intended to add value across the city, no plan fully considered what equitable distribution would mean. There was also limited-to-no engagement with the concept of contextual value, that the perceived value of GI may vary between communities and settings. And unlike best-practice cities, plans do not discuss the risks posed by value increases from GI projects, examine the causes of unequal distributions of environmental amenities and hazards, or how some communities have been made more vulnerable than others.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Despite a number of initiatives that have the potential for integration, green infrastructure planning in the District of Columbia remains fragmented with poorly articulated mechanisms for community engagement. DC is one of the fastest gentrifying cities in the country and has finally started growing its population again after decades of decline. World-famous congestion and burgeoning demand for alternative transit, walkable neighborhoods, high quality of urban life, and mounting climate risks all demand an expansion and improvement of a city-wide multifunctional green space network. Without community leadership and mechanisms for marginalized communities to have ownership over planning, it is unlikely current efforts will address the concerns of those facing housing displacement and dealing with systemic inequality caused by previous planning efforts. The city has garnered national attention for the creation of a community land trust in some of the lands surrounding the 11th street bridge project and attempts to ‘green’ southeast DC in place. Although given the displacement that has already occurred in inner southeast and Capitol Hill, it is unclear how successful this approach will be. The history of community organizing around housing is strong in DC and the city was a leader in the housing coop movement. To have a more equitable GI system, existing avenues for housing affordability should be strengthened as the city continues to make necessary investments in a multidimensional green infrastructure network.

Community Groups

Numerous national organizations are based in Washington DC and focus on large-scale policy change (e.g. We Act). However, these organizations are not grounded in local issues facing current and long-term residents. A host of community groups have been working on economic justice and housing advocacy within the District, such as DC Jobs with Justice and others supported by the DC Childcare Collective. However, these broad coalitions do not appear to be focused on climate resilience or green infrastructure issues. Other environmental justice initiatives focus largely on ongoing toxic waste issues but intersect with the Long-Term Control Plan to some degree because they include the city’s Blue Plains Sewage Treatment Plant. Opportunities exist for these organizations to coalesce around a just transition framework, simultaneously addressing housing, environmental justice, urban redevelopment, and labor issues. In solidarity with these ongoing efforts, we provide several concrete recommendations below.

1. From Increasing Value to Restorative and Transformative Justice

The dominant rhetoric in DC GI plans is that of increasing the value of the urban environment while cost-effectively complying with regulations. While improvements in infrastructure systems are certainly necessary, their potential impacts should be framed by the concerns of those who have been most marginalized by existing planning processes. For example, using percentages of market-rate housing costs as a criterion for affordability guarantees a majority of current Black residents will not be able to afford newly developed ‘affordable housing’ without structural economic change due to the extreme income discrepancies between different populations within the district. Median white family income in the District is 3x higher than median Black family income.

A restorative justice framework was utilized by previous DC administrations to build successful programs for youth empowerment, which led the city’s cultural revival following the race riots of the 1960s and subsequent mass exodus to the suburbs. Transforming how city planning occurs to address restorative justice will require coalitions of interest groups that have been historically fragmented and often antagonistic, such as nature conservation groups, and those concerned with housing and racial justice. The only existing framework that addresses jobs, housing, and environmental quality is that of a just transition.

2. Equitable Equity Evaluation

Like other cities, DC has created formal mechanisms, namely the Council Office on Racial Equity, for evaluating the equity of city policies and decisions. However, the framing of equity issues centers on eliminating racial disparities and prevents using race as a criterion for additional investment in communities and neighborhoods. While this logic is understandable, a larger transformation is necessary for communities themselves to evaluate the equity of city decision making, which they have often done quite vocally, but with limited uptake into city policy. While the existing Advisory Neighborhood Councils (ANC) do allow for some local control of planning and zoning decisions, they are also notoriously unreliable and often favor the interests of developers over community members. Evolving the ANC model to have direct votes over major proposals affecting neighborhood quality of life would be one strategy to allow for immediate feedback from communities on development plans. At a minimum, existing initiatives to address equity analysis should have a clear and transparent process to document and address public input, otherwise, equity washing will remain rampant.

Policy Makers & Planners

Planners and policy makers in DC currently have an outsized role in shaping the city’s green infrastructure programs. Despite related planning around habitat, environmental quality, and parks and recreation, these plans have no underlying conceptual unity for linking multi-functional green spaces with built infrastructure systems. Simultaneously, plans are largely silent on the social equity concerns of transformative environmental planning. To address these twin gaps, policymakers and planners can undertake three related projects: broadening the scope of current GI concepts, integrating existing planning efforts into a more cohesive city-wide vision responsive to the needs and demands of diverse residents, and embracing the idea of a just transition to go beyond GI when addressing GI’s social impacts.

1. Going Beyond a Stormwater Concept With an Integrated Green Infrastructure Concept

Green infrastructure-focused planners in Washington DC have largely implemented a stormwater control concept to comply with the EPA’s regulations. They have been significantly hampered by a lack of jurisdiction of almost 40% of the District’s impervious cover, which is on federal property. In the face of such a fundamental constraint, greater coordination with federal agencies and property owners is certainly necessary to meet their runoff control goals. Progress on this coordination has been slow and devastating to project budgets.

Recognizing green infrastructure as a network of diverse green spaces that mesh with engineered systems to meet multiple social goals will give planners more leeway for planning interventions that will contribute to stormwater compliance, even if they are not formally considered as control measures by the EPA. An approach that goes beyond stormwater compliance is necessary to address the myriad of climate change impacts, which will profoundly affect the District’s most marginalized communities. Currently, only the habitat conservation plan seriously addresses the topic of heatwaves and flooding, both of which can be significantly mitigated through a city-wide green infrastructure network.

The District has ample space for housing its current population and, with increases in density, could house significantly more people than it presently does. So, a serious conversation needs to be had on how to make space for nature and floodwater within the existing urban matrix. The Habitat Conservation Plan’s analysis of the impacts of climate change on different habitat types could be integrated into a large-scale planning framework, such as the Comp Plan, to create active transit corridors, daylight urban streams, and provide street tree canopy while improving higher density housing.

2. Integrating Disparate Plan Efforts Into a Cohesive Citywide GI Planning Process

With a more integrated concept and vision of GI, planners and policymakers in DC can start to integrate existing plans including the Vision Zero transit safety plan, the Parks and Rec Master Plan, the DC Habitat Plan, and the Anacostia Restoration Plan with limited bicycle planning efforts and stormwater planning through a comprehensive and community-led planning effort. While some planning efforts address a portion of this need, such as the small area planning process, the recent update to the city’s Comprehensive Plan, and the update of the city’s Parks and Rec Plan, they do not have any underlying conceptual unity with regards to planning for urban environmental quality. Environmental protection, infrastructure, parks, and open space are all treated as separate planning themes. A city-wide GI plan using an integrated concept of GI would allow for these separate planning processes to collaboratively envision and enact a more liveable future across the city. To ensure such a process is truly equitable, planners will have to evolve current inclusion and engagement mechanisms and invest a portion of their current budget surplus into community planning councils.

3. Going Beyond GI to Address GI’s impacts Through a Just Transition Approach

As in other cities, the social concerns impacted by GI planning cannot be addressed by GI planning alone. Housing, jobs, and environmental justice all require structural economic transformation and yet are deeply intertwined with urban quality of life, urban form, and the types of built infrastructure systems that urban residents rely on. A just transition approach focuses on eliminating polluting industries by transitioning to a clean and circular economy, improving the quality of housing, and valuing the labor required to do so. While the city historically had many manufacturing jobs, current opportunities are limited to government employment, consulting and government contracting, nonprofit sector employment, and the service industry. Reestablishing urban industries and focusing on creating more high-value labor opportunities in historically marginalized communities are necessary steps to build wealth with GI and prevent further housing displacement.

Foundations and Funders

Washington DC is the nonprofit capital of the world. And yet, extreme disparities in life expectancy, housing affordability, and incomes are remarkably persistent despite a vigorous and public culture of organizing in the city. While not a panacea, a city-wide green infrastructure system utilizing a just transition framework can address some aspects of systemic racism by creating high-paying jobs, improving environmental health equitably, and reducing cost burdens for infrastructure. While there are many potential avenues to iteratively improve the equity of GI planning in DC discussed above, we focus on one key recommendation for funders looking to have a positive influence in the city.

- Good Green Jobs Instead of Nonprofit Precarity

Foundations, funders, and city government have all contributed mightily to the proliferation of nonprofit organizations fulfilling the civic roles once held by steadily employed public sector employees. Overall, this has contributed to the creation of an ever more precarious workforce, staffed by transient young people from outside of the city on their way to higher-paying jobs elsewhere. This neoliberalization of social and environmental governance has failed to produce the changes in society and the environment that it promised. The decline of public sector employment in the District has had a profound impact on the city’s Black community - who benefited from the growth of well-paying government jobs with defined pension plans. A green jobs force, as envisioned by many in the just transition movement, requires both dedicated public funding, and mechanisms for cost recovery. The current model of foundations funding nonprofits to do public sector work is inherently unsustainable. Rather, foundations and funders can support organizations working for structural change, which will eventually make their work obsolete.

Closing Insights

The Nation’s Capital highlights all of the tensions we have observed across cities in the US attempting to address equity with green infrastructure planning. These include a circumscribed or limited GI concept, a lack of clarity around the meaning of equity, and inconsistent means of including communities in the decisions that affect residents' lives. To embark on a new era of GI planning that addresses systemic inequalities, we envision a paradigm shift around ecological urbanism and a just transition, which entails direct democratic governance of infrastructure and urban planning.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.