NEW ORLEANS

Incorporated 1718

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 169.4 sq. miles

- 389,648 Total population

- 2,299 People per sq. mile

- 0.5% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 1.9% Developed open space

- $39,576 Median household income

- 17.8% Live below federal poverty level

- 71.7% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 19.7% Housing units vacant

- 0.1% Native, 30.7% White, 58.9% Black, 5.5% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 2.9% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The City of New Orleans occupies the homelands of Chitimacha peoples and other Indigenous Nations, although this history has largely been erased. Native and Black identities are deeply intertwined through legacies of colonialism, slavery, resistance, and organizing. At the mouth of the Mississippi River, one of the largest, most heavily managed, and industrialized river basins in the world, the city faces profound long-term challenges related to river basin management, coastal habitat loss, rising sea levels, and increasing extreme weather associated with climate change. The city has served as an epicenter of conversations over climate justice since even before the devastation of Hurricane Katrina.

While in many ways the city has rebounded, redevelopment and regeneration have been highly uneven and rife with climate gentrification. Despite population growth, many residents from marginalized communities displaced by the hurricane have been unable to return home.

Green Infrastructure in New Orleans

New Orleans’ GI programs focus almost exclusively on implementing a stormwater concept through the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans (SWBNO) stormwater management and GI plans. Additional planning support for GI in the city comes from the New Orleans Master Plan (Plan for the 21st century) and the City of New Orleans Capital Improvement Plan.

Plans examined were in broad agreement about what constitutes GI, including ecological elements, engineered facilities, and green materials, although they did not include parks or greenspaces.

The functions of GI were focused on integration with the stormwater and flood control systems, as well as restoring some ecological functions of coastal habitats.

The benefits of GI were also focused on improving environmental quality and built infrastructure performance, as well as positioning the city as a leader in the water management sector.

Key Findings

The New Orleans Comprehensive Plan offers a strong framework for considering equity issues across city programs including GI planning. In the remainder of the evaluated plans, equity is not addressed directly or with any vigor. While plans seek to address the enormous disparities in exposure to the hazards managed by GI, mechanisms for public engagement are sparse and notions of justice remain underdeveloped.

25%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

25%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

25%

define equity

25%

explicitly refer to justice

75%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

25%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

25%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

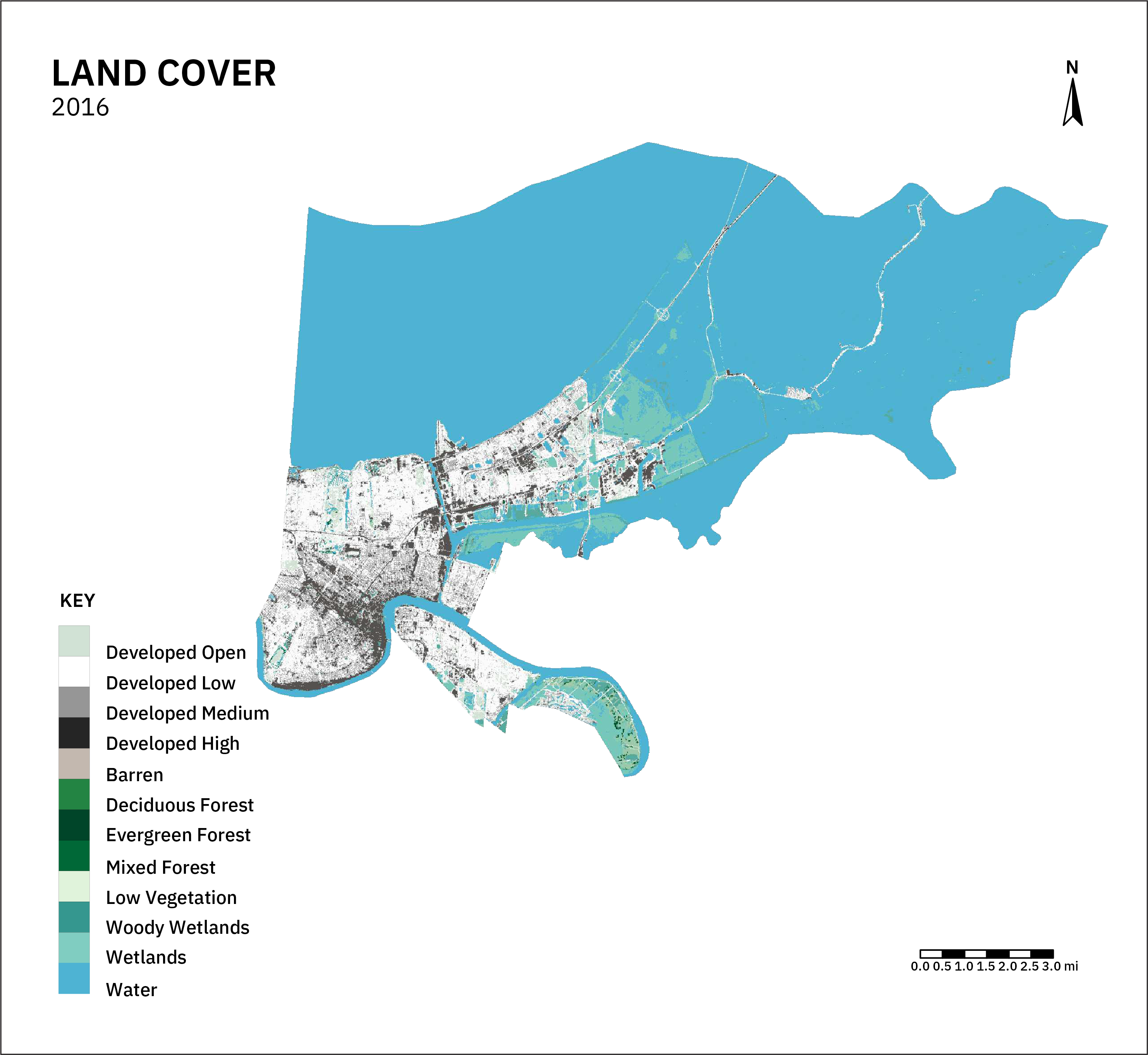

New Orleans through Maps

The City of New Orleans is divided by the largest river in North America, the Mississippi River. Abundant freshwater and coastal marshes line the city’s eastern outskirts and much of the area within the city limits consists of water. The aqueous city has several higher elevation zones forming much of the denser parts of downtown and the backbones of historic neighborhoods. The city remains segregated racially and economically, with highly uneven distributions of income and rent burden.

How does New Orleans account for Equity in GI Planning?

New Orleans’ Comprehensive Plan is one of the few plans that addressed each of the 10 dimensions of equity we examined with our screen. Written in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the plan uses a definition of equity that focuses on inclusive government and fair outcomes by confronting institutional racism and discrimination. Otherwise, framings of equity issues were weak and we found no other definitions of equity or justice within the other three plans.

While the Comprehensive Plan focused on inclusionary planning, procedures for public engagement across the GI lifecycle require further development.

Plans emphasize the role of green infrastructure in mitigating the highly uneven distribution of urban stormwater and flood hazards but with limited discussion of the value of GI and the labor it requires.

Envisioning Equity

The Comprehensive Plan grapples with both the legacies and the present realities of institutionalized racism contributing to the inequities present in the city today. Its vision for GI is largely rooted in a notion of universal good, though it also acknowledges the failures of prior planning efforts and persistent frustrations in the city’s marginalized communities. The Plan also discusses environmental justice, borrowing language from the state constitution which bans discrimination based on race in siting decisions. However, concepts of restorative and transformative justice are absent. This omission could allow for the persistence of institutionalized racism, and top-down styles of decision making that do not take into account the varied needs or experiences of communities themselves.

Procedural Equity

Following a pattern similar to many other cities, the Comprehensive Plan used numerous avenues to garner public input in its initial stages. The timeline for public engagement was, however, compressed, and several planning units appear to have merged without input from those living in them. Also, it isn’t clear what demographic groups were engaged or solicited for participation or how. While the plan selectively reports public comments, there is no way of knowing what other concerns were raised and then dismissed by planners. Other city plans were much weaker in their methods of public inclusion. It also appears that planning for compliance with water quality regulations within the city required local activist groups to sue the city. There are no substantive mechanisms outlined within plans for participatory design and program implementation. Current mechanisms for design and implementation are led by city agencies, and, in some cases, rely on an RFP process requiring communities to lead their proposals in a competitive bidding process. Plan evaluation also lacks clarity and substance. Although GI programs are monitored for their physical performance, there are no monitoring or reporting mechanisms in place for the larger set of concerns around GI’s social impact.

Distributional Equity

Not surprisingly for a post-disaster city, the comprehensive plans acknowledge many intersecting and differential hazards and prioritize GI projects in those communities that have higher exposure. However, the differential vulnerability approach, namely, acknowledging that some communities have been made more vulnerable over time due to how hazards are managed, is not referenced in the overall stormwater management plan, despite being mentioned in the city-wide GI strategy. Planning efforts to manage flooding and water quality risks intermittently reference the need to make transportation networks safer, but fail to focus on other overlapping climate hazards, such as more frequent heatwaves. Although both the Comprehensive and GI-specific SWNBO Plans describe that GI has many valuable aspects, these are considered to be universal and independent of context or the needs and perceptions of communities. The Comprehensive Plan acknowledges the need to address the potential for housing displacement but does not specify any ways to deal with the issue. This is problematic because the plan intends to target marginalized communities for GI interventions but offers limited mechanisms for those communities to influence the process. Approaches towards addressing labor distributions are largely undeveloped. The Comprehensive Plan borrows from Milwaukee’s ‘Water Centric City’ concept but without elaborating on specific job training programs. City plans for GI explicitly rely on volunteer labor and in-kind donations but do not discuss the equity implications of doing so.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

The City of New Orleans in combination with Policy Link and the Government Alliance on Race & Equity has committed to creating the Equity NewOrleans initiative. Despite several promising attempts to address equity through GI planning, there are notable gaps. Below, we outline several key areas to improve the City’s GI planning in collaboration with community groups, city officials, and funders.

Community Groups

City leadership’s commitment to equity must extend to the public realm investments in the city’s green infrastructure systems. The significant expenditures being made at both the city and federal levels to counteract flooding and improve the city’s storm and sewer systems must also support communities on the frontline of climate change. The long history of creative resistance to displacement by frontline communities in New Orleans is being severely tested by climate gentrification. In the current political climate, community groups can push to fill several key gaps in how current GI plans address equity issues.

1. Demanding Genuine Inclusion

While the Comprehensive Plan collected survey data in its formative stages, there are no substantive mechanics outlined for incorporating community input as part of green infrastructure decision-making. Neither SWNBO led plan makes commitments to meaningful public participation or ownership of the process. Demanding genuine inclusion in GI planning processes requires that the communities determine how they are engaged. These also should include the full lifecycle of GI programs, projects, and policies, including free prior and informed consent, and all that it entails, during planning, design, implementation, and evaluation.

2. Addressing Housing Displacement and Climate Gentrification

Managing stormwater and flooding are premier environmental justice issues in New Orleans but green infrastructure mitigation measures must not contribute to the further displacement of the city’s marginalized communities. Communities facing GI-related displacement should demand that planners make good on promises in the Comprehensive Plan by following the guidance of anti-displacement campaigns such as greening in place.

Policy Makers & Planners

New Orleans City Planners have made commendable improvements in the most recent Comprehensive Plan to address some equity dimensions of GI. As our analysis above points out, work remains to be done to ensure that GI can address long-standing injustices to equitably manage hazards and improve the public realm. To that end, we offer several recommendations to address the gaps in current GI plans.

1. Building Inclusion Over the GI Lifecycle

Without meaningful community engagement, GI programs will likely replicate existing inequities. Mechanisms for public engagement in the city’s current plans are lacking. Establishing dedicated resident councils and paying participants to engage in planning, design, implementation, and evaluation work is one way to kickstart the Water Centric City-based jobs concept included in existing plans and progress towards community control of resources.

2. Proactively Addressing Climate Gentrification and GI Displacement

GI can make neighborhoods more climate-resilient, vital for a city like New Orleans. However, as evidence has already shown, climate and GI can combine with structural inequality to displace residents. It should be noted that the city has stated that it will study the issue. Strategies for addressing housing displacement, including dedicated bond funds for affordable housing, and building community wealth through GI as part of larger just transitions, have demonstrated success in keeping neighborhoods affordable for current residents. The team at Greening in Place has explored other options for anti-displacement. Rather than locking residents into existing segregated neighborhoods, progressive approaches would enable tenant organizing, stronger rent controls, creative solutions like low equity coops, alongside wage and jobs growth to structurally address housing choice.

3. Advocating for GI at Scale

New Orleans flood and climate vulnerabilities cannot be addressed by the city alone. The Mississippi River, delta, and surrounding coastline are some of the most altered ecosystems in the world, and ongoing federal efforts must evolve to build long-term climate resilience for the city. Advocating for changes in the broader basin and federal coastal protection strategies are necessary alongside city-level investments in GI. Fortunately, the Louisiana Watershed Initiative provides a working framework for such a multi-scalar approach and could be strengthened to achieve equitable climate resilience for the region.

Foundations and Funders

Numerous funding organizations were identified as crucial to implementing the city’s GI plans. There are several key areas where funders could improve the equity of the GI planning process and its outcomes.

- Planning from the Grassroots

Funders can dedicate resources for community organizing around intersectional environmental, housing, and social justice issues. These issues can be partially addressed through GI, but depend on restorative and transformative justice-informed approaches towards grassroots neighborhood improvements, and in some cases, retreat. Whatever rent-burdened strategy is selected by impacted communities, foundations can support demonstration projects to serve as models for evolving city programs that oriented towards more inclusive and equitable practices. Further efforts could include supporting nationwide knowledge and skills exchanges amongst community organizations with similar struggles. Collective capacity building will contribute to a just transition in the region's fossil fuel sectors and support the realization of the Water Centric City jobs concept.

Closing Insights

New Orleans is a city of the future. The way the city handles the rising threat of climate change and how they use GI as an element to address both climate and social justice challenges will be seen as a model by many. However, doing so requires different sectors of society to work collaboratively to address the intersecting trends of housing displacement and persistent environmental and social injustice, and implement genuinely inclusive and transformative planning.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.