PORTLAND

Incorporated 1845

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

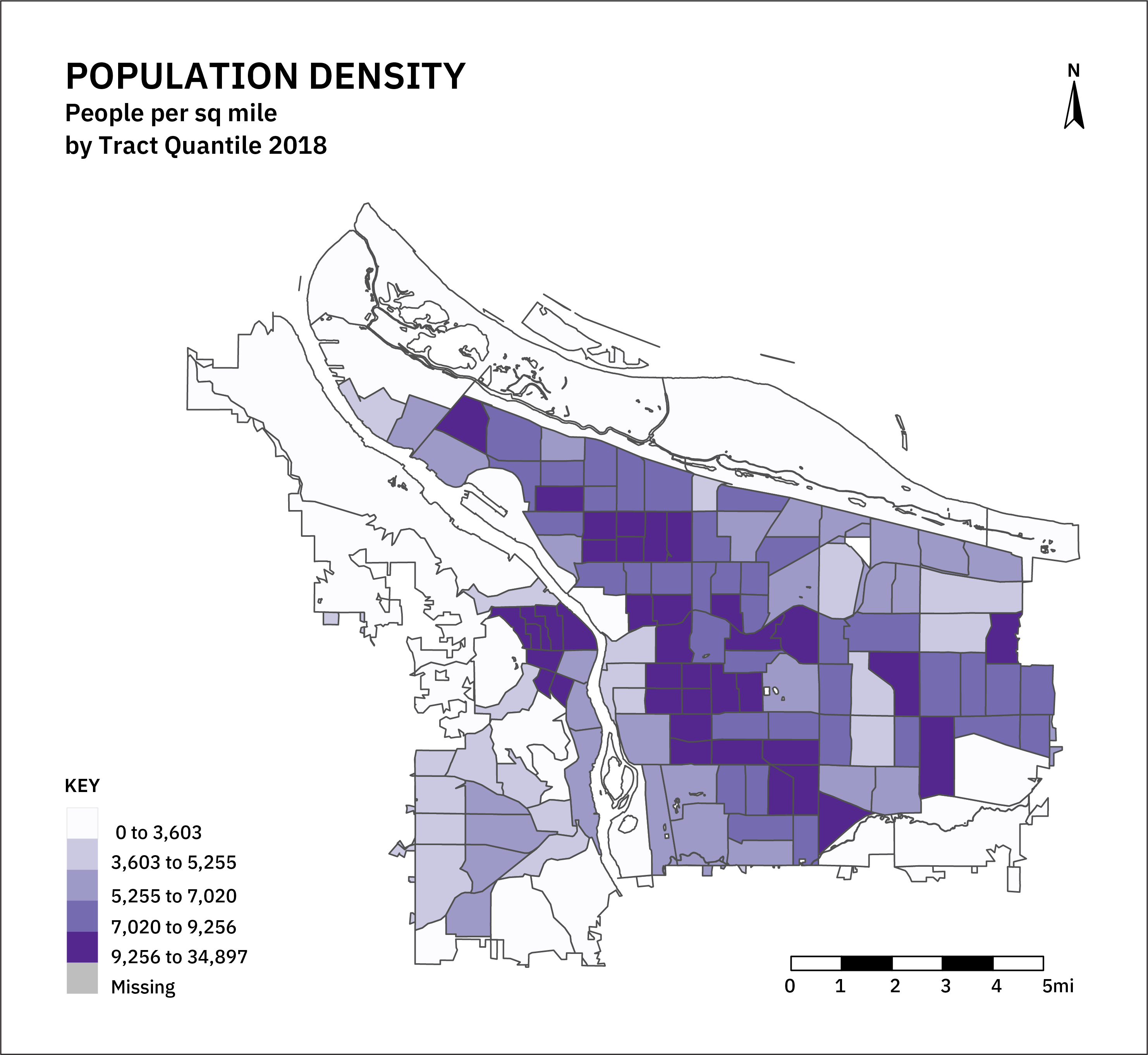

- 145.0 sq. miles

- 639,387 Total population

- 4,792 People per sq. mile

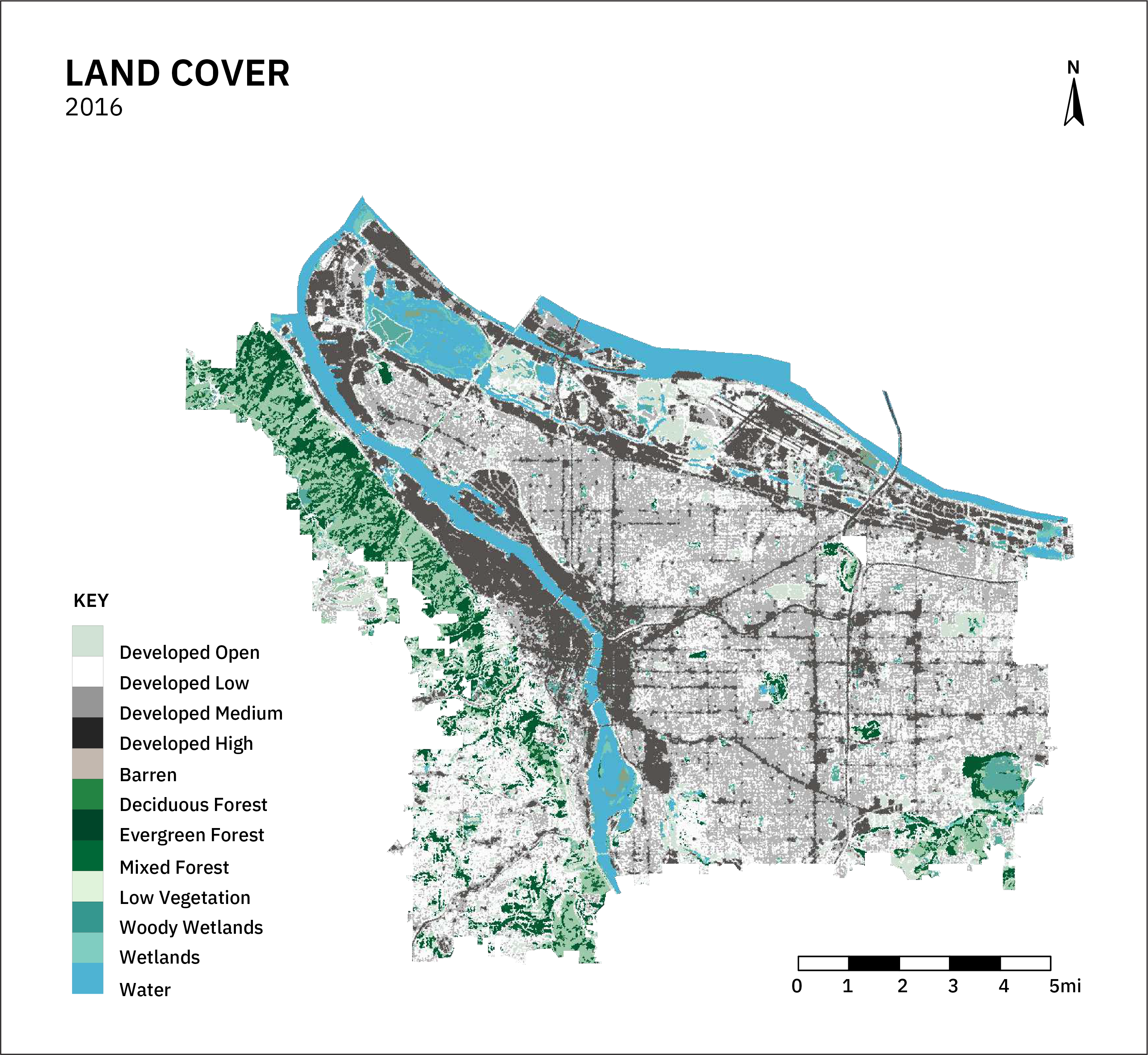

- 11.5% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 6.7% Developed open space

- $65,740 Median household income

- 9% Live below federal poverty level

- 63.8% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 6.3% Housing units vacant

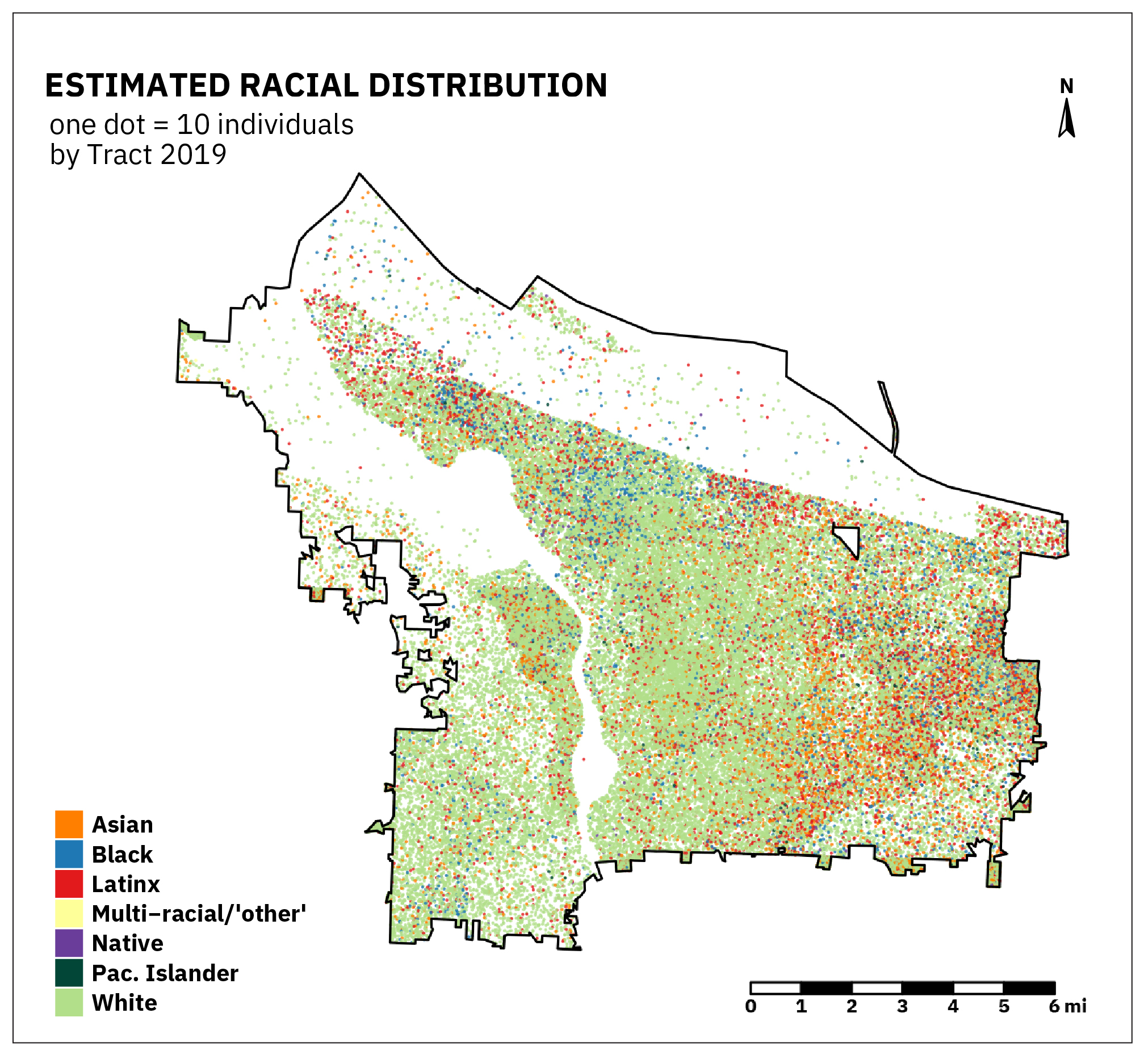

- 0.6% Native, 70.6% White, 5.6% Black, 9.7% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 8.1% Asian, 0.6% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The city of Portland occupies the homelands of a number of Indigenous Nations, lands seized through flawed treaty processes and unmet responsibilities. The city serves as a hub of resource extraction and manufacturing.

Portland’s growth has been inseparable from the development of the Columbia River Basin, and its impacts on regional fisheries, and landscapes. The city has served as a flashpoint for conversations on environmental justice, real estate development, gentrification, white supremacy, and a just transition. Citywide watershed restoration intersects with regulatory stormwater programs to improve quality of life and address the mounting impacts of climate change.

Green Infrastructure in Portland

Portland plans for green infrastructure using a wide array of planning instruments. GI is integrated into comprehensive, climate, sustainability, and transportation planning, alongside numerous watershed and stormwater planning efforts. These diverse plans reinforce one another by having a high degree of conceptual integration, with only a few instances of landscape and stormwater-specific concepts, and several plans that do not define GI.

Despite the use of integrative GI concepts, Portland GI plans fall in the middle of the pack in terms of the diversity of elements formally considered Green Infrastructure. Plans focus on a number of defined facility types, including street trees, and bioretention and stormwater facilities, but omit parks, networks, corridors, and trails.

Portland plans seek to provide key social, environmental, and technological services with GI, despite the employment of a limited number of GI elements. Named functions include improving transportation, providing a sense of identity, regulating heat, improving air and water quality, alongside the main focus on stormwater management.

Similarly, in line with its new urbanist planning paradigms, Portland GI plans define a wide array of benefits related to urban quality of life, climate resilience, and improving environmental quality alongside the performance of grey infrastructure systems.

Key Findings

GI Plans in Portland attempt integrative city-wide planning, but functionally only focus on stormwater control measures. Some plans center equity and justice concerns with robust definitions, visions, and public participation processes. Many others do not and are problematic in their use of urban greening within extensive redevelopment proposals.

89%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

56%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

89%

seek to address climate and other hazards

77%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

56%

define equity

44%

explicitly refer to justice

88%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

22%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

56%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Portland through Maps

Portland is a predominantly white city, which is not surprising given its legacy of overt racial exclusion and white supremacy, which were part of official state policy. Many minoritized communities have faced serial displacement, and patterns of segregation in the city reflect rates of rent burden and differences in incomes. The city’s vacancy rate appears to be driven by areas of speculative real estate development, with some exceptions, and is generally much lower than older east coast cities. A dense urban core is surrounded by low-density neighborhoods. Several large parks provide the majority of the city’s green space, with smaller and medium-sized parks unevenly distributed throughout the city.

How does Portland account for Equity in GI Planning?

Portland GI plans address equity idiosyncratically. While the Portland Plan, 2035 Comprehensive Plan, and Climate Plan address all 10 dimensions of equity, with the latter two offering best-in-class definitions and framings, sewer and stormwater system plans are essentially silent on equity issues.

Methods of public engagement are similarly spotty. Despite several plans emphasizing and showcasing participatory planning practices, few mechanisms exist for substantive and binding public engagement through the rest of the planning life cycle.

Portland GI plans display more consistency in addressing existing disparities in the distribution of hazards and with intentions to add value to the urban landscape. Plans weakly address labor issues, if at all.

Envisioning Equity

Several Portland GI plans stand out for their thoughtful definitions and framings of equity and justice, which represent best practices in this body of plans, but still fall short. For example, the Portland 2035 Comprehensive Plan addresses distributional, recognitional, and procedural elements of equity and justice, but does not include transforming decision-making processes. Instead, they rely on inclusion in an overall framework of mitigating rather than eliminating harm. The Climate Plan similarly advances redistribution of benefits and burdens through intentional and targeted policies, but not transforming the policy making process itself. Framings of equity and justice are pervaded by a deficit framing centering the need to increase opportunities and amenities for disadvantaged communities. The strong definitions within the 2035 Comprehensive Plan inform both the Transportation and Central City Plans. Other plans either use much weaker definitions or none at all. The city’s plans frequently refer to the Portland Equity Framework, which appears to be an elaboration of the Portland Plan’s definition of equity and not a binding set of policies or procedures.

Justice was less consistently addressed than equity. The Climate Plan provides a strong definition drawing upon transformational justice concepts in the climate justice movement, emphasizing that how under-represented groups are included in decision making must change, rather than just changing the distributions of risks and benefits through city agency initiatives.

Procedural Equity

In comparison to many other cities, Portland plans emphasize inclusive planning practices. These stress the importance of affected communities participating in city planning decisions and their implementation. This rhetoric, however, did not appear to be backed by any specific or binding mechanisms, procedures, or dedicated resources for community involvement in designing or implementing GI policies, projects, or programs. Additionally, Portland plans had very few mechanisms for communities to meaningfully evaluate the efficacy of plan implementation. One exception, the Transportation Plan, included a best practice for responsible community engagement. That plan calls for an independent review committee to assess the process and outcomes of its specified community engagement practices as part of the plan’s implementation. Yet, even in that case, it was not clear who would comprise the committee and how the needs, concerns, and experiences of the involved communities brought to light in this process would be addressed.

Distributional Equity

Portland GI plans extensively discussed the distributional equity of GI in terms of its relationship with intersecting urban hazards and the multi-faceted nature of the value of urban space. Plans were much weaker in discussing labor issues associated with GI. Several plans, including the Comprehensive and Climate Plans, stressed the importance of using GI embedded within the urban form to manage climate-related hazards. Plans also acknowledge the relationship between GI investments and the potential for housing displacement but did not meaningfully address it through proposed interventions. Policies targeting marginalized communities for GI improvements without mechanisms in place to address displacement are highly problematic. The same plan framed labor inequalities as a problem of building greater ‘upward mobility’ without naming and examining the uneven and racist conditions that are part of existing labor markets and wage inequality.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

The City of Portland, like many others, has a dedicated Office of Equity and Human Rights charged with ensuring that city agency decisions address racial and social equity issues. Portland plans are also somewhat unique in the breadth and depth of discussions of equity issues in the city, and their much greater consistency in defining and naming equity and justice issues in comparison to other cities. However, notable gaps remain in how city plans conceptualize and operationalize equity and justice issues, despite decades of steadfast coalition-based community organizing.

Community Groups

Numerous community groups have tirelessly advocated for environmental and social justice within the City of Portland. These same communities have faced displacement due to urban renewal and highway development that affected most if not all of the city's ethnic and racialized communities while sparing the city’s predominantly white western downtown. The demands of community groups have in many ways created the progressive image and stance of Portland administrations. They will likely continue to be the primary force for positive change, given the city’s ongoing rapid transformation as a global hub of speculative real estate investment, and significant conflicts of interest affecting those governing existing planning processes. Below we offer ways to address several key issues and gaps within current plans that may support community organizing efforts towards just GI systems.

1. Demanding Transformation in City Planning and Decision Making

Portland plans are big on community inclusion, and the engagement of communities in decisions that affect their lives appears to be mandated by the Comprehensive Plan. However, with no specified forums, or resources for communities to become informed about the nature of ongoing city planning efforts, existing conflicts over green infrastructure and housing issues will likely be exacerbated by the scaling up of city greening efforts. Community groups can and should push for meaningful mechanisms of inclusion based on principles of Free Prior and Informed Consent, have the city provide resources for communities to lead their own planning and evaluation processes, and have binding mechanisms for dispute resolution.

2. From ‘targeted investment’ to reparations

Minoritized and oppressed communities in Portland do not need more targeted investment by outsiders or by a city government that has failed to prevent record-breaking rates of gentrification. Community groups can and should call for reparations for prior decisions that have caused harm, especially given the apparent willingness of planners to admit to past wrongs.

Policy Makers & Planners

The City of Portland is internationally recognized for struggling with equity and racial justice issues. Progressive administrations and plans must go beyond the rhetoric of inclusion and address structural inequalities in the city affecting the equity of green infrastructure. The city has taken on massive cost burdens for Clean Water Act compliance and has undertaken numerous watershed planning and protection initiatives. It has also led the conceptual integration of green infrastructure into urban form. Despite all this progress, green infrastructure approaches remain siloed within a stormwater management focus. Below we offer several tangible recommendations for addressing gaps in current plans.

1. Genuinely Integrated Green Infrastructure

Portland plans utilize integrated green infrastructure concepts, yet omit key urban ecological elements such as parks, trails, farms, networks, and corridors. At the same time, the city has taken on large-scale floodplain and riparian restoration projects, extensive tree inventories and tree planting, and promoted complete street design standards. The city should go further in promulgating an urban ecological infrastructure approach that considers all of these interconnected ecological elements cohesively and supports individual, community, and city agency efforts to weave together ecological and infrastructural elements throughout the city. Without such fine-grained integration, the multiple desired benefits of GI will not be achieved. Such an approach omits the creation of ecological sacrifice zones and will be required to scale current efforts to equitably green the city across all neighborhoods, especially those currently lacking GI.

2. Get Serious about Transforming Systems that Cause Harm

Portland planners conceive of themselves as progressive in their targeting of marginalized communities for additional GI investments. This is certainly an admirable goal in terms of reducing disparities in access to environmental goods. However, without addressing underlying structural inequalities in employment, intergenerational wealth transfer, and policing, among other issues, such targeted investments in a landscape of inequality will continue to accelerate housing disparities and displacement. The only way to address the downside of uneven greening and housing is to embrace approaches that reduce ongoing harms in marginalized communities and invest in core community capacities to lead planning and budgeting efforts, as well as shifting housing away from a speculative real estate based model using a variety of planning interventions.

3. Wealth Building through Redistributing Labor, Wages, and Expertise

Some city plans acknowledge that the majority of compensation for the labor required by GI is in the white-collar work of planning, analysis, and design, with significant compensation in construction, and scant or no resources committed to maintenance. And yet, in minoritized communities, maintenance jobs are the only ones that are made available to local community members, and may not be compensated. Building community wealth, therefore, requires either compensating maintenance labor at living wages, which are quite high given the exploding cost of living within the city, along with a serious focus on training and upskilling impacted communities to participate in other aspects of required GI labor.

4. From Exploration to Transparent Metrics, Data, and Processes

The city has committed to a comprehensive city-wide watershed monitoring framework (PAWMAP) which could be an opportunity to track broader equity metrics. The Watershed Action Plan states that these metrics will be "explored" but doesn't provide a timeline or starting point for how they will be integrated into the overall governance of programs, or utilized to adjust approaches. The city should create meaningful mechanisms to give communities power over evaluating city initiatives and changing course as problems arise.

5. Consistency Across Plans for Housing Security

There are key contradictions in some city-endorsed initiatives and planning frameworks, despite a few plans containing functional definitions of equity and justice issues. For instance, the Central City Plan acknowledges how the Lloyd EcoDistrict approach poses risks of further displacement of marginalized communities in the area, but this risk is not acknowledged within the Lloyd EcoDistrict Plan itself. Given aggressive rates of housing displacement and houselessess within the city, securing affordable housing as part of large-scale investment-oriented programs, like the EcoDistrict approach, should be a top priority.

6. Embracing the Floodplain, but not Creepily

Portland GI plans appear to focus on continued hard infrastructure investments within the floodplain to protect existing industrial uses. This poses a paradox as the disconnection, armoring, and infill of the floodplain has been one of the largest environmental impacts of urban development, and any large-scale restoration of ecological function in the city will require floodplain reconnection of both the Willamette and Columbia rivers. Furthermore, hard flood defenses are extremely expensive and maintenance intensive. Optimizing the use of existing and underperforming industrial areas and brownfields to shrink their footprints would allow for more space in the floodplain for restoring riparian ecosystems.

7. Don’t Just ‘Put an Equity Bird on It’

Portland GI plans mention equity frequently. Yet it is not always clear what is meant by the term, as they generally refer to equity as an outcome of city decision-making structures, while also acknowledging that prior decisions are a major source of current inequality. These commitments to change are admirable, but if equity does not consist of identifiable, measurable, and experienced transformations in how city decisions are made, and in their outcomes, then equity becomes just another ‘bird.’ The city must commit to meaningful, and community-defined, equitable decision-making processes and measures of what equitable outcomes of city green infrastructure programs look like, which requires going beyond current inclusion mechanisms.

Foundations and Funders

Portland GI plans, in particular the 2035 Comprehensive Plan, provide a regulatory framework for community inclusion in city-led planning initiatives. However, mechanisms of meaningful community involvement, and resources for community planning capacity building, are weakly articulated, if at all. To address long-standing justice concerns, foundations and funders can play an important role in supporting the development of equitable processes. This includes demanding transformative change in how current GI plans are implemented and ensuring that the needs of marginalized communities are centered in future planning efforts. Below, we offer a recommendation to do so.

- From Complete Streets to Whole Communities

Portland communities have led the charge on numerous environmental justice issues, and have provided working models for how inclusive, justice-oriented green infrastructure initiatives can build community wealth and address structural inequalities. Existing funding models for complete streets programs and community-led initiatives often threaten community well-being, especially in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods. Funders should move away from single project-based funding models, especially those that don’t track outcomes or invest in community institutions and grassroots organizing to push for transformative change.

Closing Insights

Equitable GI in Portland, OR requires a transformation of how current GI plans are created, implemented, and evaluated. Existing policies provide a functional start for addressing long-standing equity and environmental justice issues, but must go further in transforming the systems responsible for historical and present harms. By working together, community groups, city officials, and funding organizations can provide the necessary momentum for a just transition and an equitable city-wide GI network.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.