ST. LOUIS

Incorporated 1764

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 66.1 sq miles

- 311,273 Total Population

- 5,041 People per sq. mile

- 0.8% Forest cover

- Temperate Grasslands, Savannas, and Shrublands Biome

- 6.4% Developed open space

- $41,107 Median household income

- 18.6% Live below federal poverty level

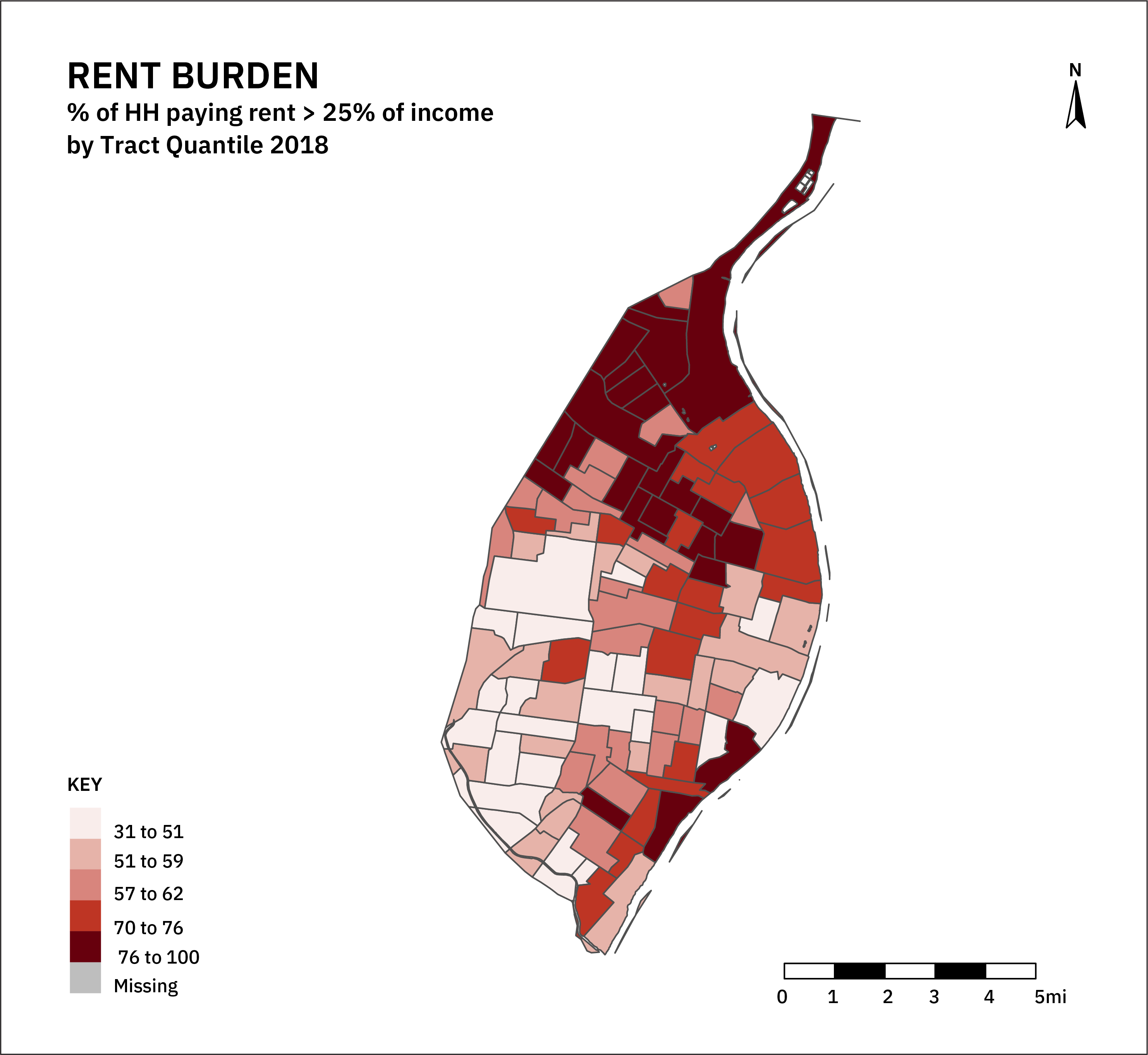

- 61.6% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 20.4% Housing units vacant

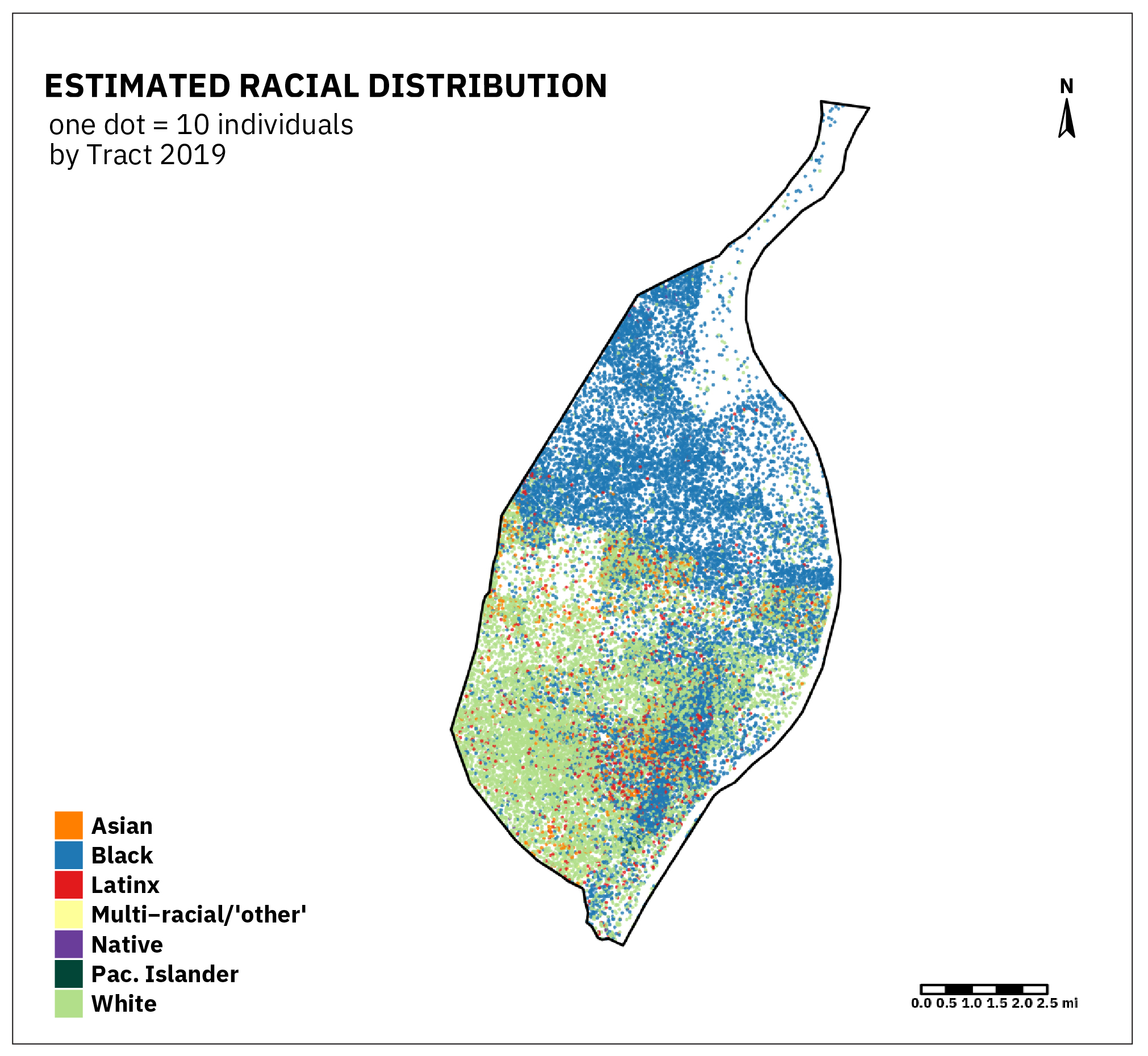

- 0.2% Native, 43.6% White, 46.2% Black, 4% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 3.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The City of St. Louis occupies the homelands of the Osage Nation. French settlers founded a trading post near the area, which depended upon harmonious relations with Native peoples and incorporated a township there prior to the land claims of the United States. With the enactment of the Louisiana Purchase, treaties with Native peoples were broken and tribes were forcibly removed to make way for westward expansion and American settlement.

Since that time, the city has had several boom and bust cycles. It has a long and complex history of its Black culture since prior to the civil war and was a pivotal area for the determination of the continuation of slavery in the USA. Built along the banks of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, the city faces climate-related hazards of flooding, heat waves, drought, and issues related to its combined storm and sewer system, which is managed by a metropolitan agency (outside the scope of this analysis). The city’s industrial sector, a major source of jobs, has yet to recover, and like many others, the city faces complex economic challenges inseparable from national policy. Contaminated brownfields face an uncertain future as St. Louis seeks to redevelop itself while addressing persistent issues of structural racism and segregation.

Green Infrastructure in St. Louis

We scanned ten documents that potentially dealt with GI planning in the City of St. Louis. Of these, we excluded several that addressed GI but were not led by the City itself, including the collaboratively written OneSTL regional comprehensive plan and stormwater compliance planning led by the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District (MSD). Green Infrastructure in the City has a complex and multi-level governance arrangement outside the scope of this analysis. City plans we did examine included the City of St. Louis Sustainability Plan and the North Riverfront Commerce Corridor Land Use Plan. While the NRCCLUP did not define GI, the Sustainability Plan explicitly used a stormwater concept of GI. Both plans seek to support regional initiatives in implementing city-scale GI focused on stormwater management.

GI Plans in the City sought to manage stormwater using a range of facility types across all categories of ecosystem elements, hybrid facilities, and green materials and technologies. Despite a diversity of elements, including trees, bioretention, blue-green corridors, green roofs, and rain gardens, plans omitted discussion of trails, networks, agricultural areas, and floodplains.

Functionally, GI plans focused on a range of hydrological functions seeking to manage stormwater flows through a variety of means (e.g. infiltration, retention, flow attenuation) along with improving water quality and the performance of the stormwater system.

Key Findings

St. Louis’s Sustainability Plan focuses on equity and sought an inclusive process of plan creation, yet does not address all ten dimensions we evaluated. The North Riverfront Commerce Corridor Plan mentions equity but does not address equity issues other than a general focus on supporting future economic development. Many opportunities exist to improve the equity of St. Louis GI Planning, but these will likely require changes in metropolitan planning systems.

100%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

50%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

50%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

St. Louis through Maps

An older city within a large metropolitan area, St. Louis has a dense urban core and riverfront area, surrounded by a lower density grid with several large open spaces and evenly distributed smaller municipal parks. The city is extremely segregated with regards to race and income, patterns reflected in vacancy rates of housing units, and rent burden. While the Northern riverfront is intensely developed, it has a very low population density compared to the southern portions of the city.

How does St. Louis account for Equity in GI Planning?

No plan in St. Louis defines equity. The Sustainability Plan does draw upon equity as a core concept, and provides a basic framework for equitably planning for GI, but falls far short of sustainability planning efforts in other cities. GI is primarily seen as a tool for cost-effectively managing stormwater while fostering redevelopment.

Envisioning Equity

The Sustainability Plan devotes a whole plan section to discussing equity without ever defining it. It also omits any real discussion of historical problems or the causes of current inequalities in the city. It considers itself a best-in-class plan and a leader in addressing equity issues. Yet, it utilizes a problematic frame, one that deems the goals of fostering innovation and gentrifying the city through the attraction of motivated young professionals into historically marginalized areas in need of redevelopment as desirable. With an absence of discussion about the causes of inequality, it is not surprising that the city has such an unmet demand for justice. Community survey responses within the plan identified segregation and diverse racial disparities (e.g. income, housing quality, environmental quality, policing) as primary planning challenges. These challenges do not appear to be substantively addressed by the plan itself, especially with regards to green infrastructure which, to be fair, has a very limited conceptualization of providing stormwater services. The vision for the North Riverfront Plan focuses on business development and neighborhood improvement and does not appear to grapple with causal processes of inequality. Like the Sustainability Plan, it is extremely future-facing and omits any discussion of how historical planning decisions have contributed to the landscape of inequality today.

Procedural Equity

The Sustainability Plan undertook a multipronged outreach effort, representing current best practices in plan formulation. However, many of the stakeholders identified and involved were selectively invited and disproportionately represent the business community. The concerns of survey respondents are not substantively addressed and the presentation of survey responses does not allow for the assessment of population representativeness, especially marginalized communities.

The North Riverfront planning process was led by special interests. Although multiple public workshops were held, their purpose was to 'inform' and receive limited feedback, and were primarily attended by businesses. The outreach strategy was not well-defined, and ultimately, the plan was oriented towards business development.

In terms of designing policies and programs, the North Riverfront Plan included conceptual design development in its workshops, but again, the approach was not inclusive. The Sustainability Plan emphasized the role of design competitions with some limited partnerships between city agencies and community groups to foster innovation but did not discuss how a competitive model may further disadvantage marginalized communities.

Implementation-wise, the city appeared convinced that the public would voluntarily implement many of the initiatives identified in both plans, even though there are no clear mechanisms or funding systems in place to support community-led implementation. The North Riverfront Plan commits to the Sustainable Tools for Assessing and Rating communities (STAR) rating system as an evaluative mechanism, has clear performance targets for stormwater GI facilities, and provides a direct route of communication for implementation concerns but it is not clear if there is a formal manner for addressing the concerns of affected communities. The Sustainability Plan includes several metrics but has no built-in mechanisms for assessing plan impacts.

Distributional Equity

Despite city commitments to understand historical racism, GI Planning in St. Louis does not robustly consider distributional equity issues.Plans seek to manage several hazards related to flooding, water quality issues, and traffic safety along with blight and environmental hazards but do not discuss their uneven distributions or injustices. Plans also look to use GI to add multiple values to the urban landscape but fail to acknowledge the context or potential downsides of targeted investments, especially in marginalized communities.

Plans have limited discussion of labor issues. The Sustainability Plan focuses on the need for sustainable job development but does not connect this need with city-wide GI development. The North Riverfront Commerce Corridor Plan focuses on the job opportunities associated with redevelopment and new business development but also does not connect jobs growth and GI.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

St. Louis is another midwestern city with extensive stormwater-focused GI programs that seeks to use GI as part of larger-scale redevelopment efforts. These programs, however, are run by the metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District, which has been a leader in the implementation of Green Stormwater infrastructure. Thus, there remain many opportunities to improve GI planning equity at the city-scale, even with more than a decade of GSI implementation in the region.

Community Groups

St. Louis has large coalitions of community groups working on environmental justice issues, many of whom have been deeply involved in other ongoing struggles for racial and social justice. The city’s rich organizing history and culture have survived numerous eradication attempts and continue to be involved in local, national, and international movements for social justice. Yet, the vision and determination of these groups are not reflected in current city GI planning, despite the existence of community-created plans that seek to address environmental justice through commitments of public resources and democratic planning. Central issues of existing justice coalitions, including worker’s rights and health disparities, can be partially addressed through just transition-focused GI planning and development.

1. Supporting Just Transition through integrative Green Infrastructure

St. Louis’ US representative Cori Bush has been an outspoken advocate for addressing climate justice and a just transition in the city and beyond. A just transition in St. Louis can be supported through city-wide GI planning that takes into account the varied needs and perceptions of marginalized and oppressed communities. A city-wide GI network to address the city’s climate challenges, and not just its storm and sewer system issues would require elaborating a place-based vision for a more integrative concept of GI than just water treatment facilities. It would include networks of alternative zero-carbon transit, street trees, and restored riparian corridors coupled with broader renewable energy, building rehabilitation and housing programs that provide well-paying jobs to residents. It would also entail a justice-focused conception of GI in the city that centers Native relationships and visions with the land. Such an effort can be supported by existing community-focused research projects seeking to address multidimensional equity issues in the city, such as St. Louis University’s Institute for Healing Justice and Equity. Further, coordination for the creation of a just vision for regional GI that includes Indigenous foodways can leverage the relationships supported by the Whitney Harris World Ecology Center at UMSL.

Policy Makers & Planners

St. Louis City policy makers and planners have not engaged with issues of equity in their current GI plans. In contrast, St. Louis County has committed to an equity planning process. but it is not yet clear what influence it will have on the city. Suburban St. Louis, especially in the wake of the Ferguson uprising, has been a pivotal arena for how equity planning can positively influence deeply fragmented cities dealing with systemic injustice. Policy makers and planners could greatly assist grassroots-led efforts to achieve social and racial justice in the city through two related avenues.

1. Integrative City-Wide GI

The city of St. Louis faces several climate-related challenges that intersect with legacies of environmental injustice and urban spatial planning, namely extreme heat, droughts, flooding, and water quality. Green Infrastructure can mitigate the impacts of climate change and address pollution issues but must be integrated into the city’s ecosystem as well as built infrastructures. Such a vision for GI in the city goes beyond the water quality mandate set by the Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) consent decree to address combined sewer overflow issues. Since the city is not the lead entity on Green Stormwater Infrastructure planning, it can put forth a more integrative vision of a city-wide GI system and use this to guide investments in GSI and other green assets - potentially aiding MSD in achieving compliance at a lower cost. An integrative vision of Green Infrastructure includes diverse networked habitat types, engineered facilities, and clean technologies. An integrative approach can also increase the equity of the current park system by focusing on creating new types of green spaces in disadvantaged communities, so long as they are attentive to the concerns of the need to green in place.

2. Transforming Planning to Address Equity and Injustice

If city plans do not define and commit to equity and justice principles, they are unlikely to address equity issues. Policy makers and planners can study the resources that have been compiled on the meanings of equity and justice, along with our evaluative tool, to embed an understanding of equity within current planning systems. The transformation of current city-based GI planning practices will be necessary so that communities become leaders in, and beneficiaries of, planning efforts.

Foundations and Funders

Environmental organizations in St. Louis continue to grapple with internal racial equity issues. These struggles, including a lack of inclusion and an absence of major commitments to transforming current city planning systems, indicate a need to foster deep-seated change in the city’s environmental organizations and center issues of equity and justice in city planning. Foundations and funders can support the above-identified initiatives directly by supporting grassroots efforts for neighborhood and city-wide integrative green infrastructure planning. Ultimately, they must invest in community capacity to create lasting and meaningful institutional and structural change in the city’s decision making systems. Like in other cities, these types of initiatives can be unified under a just transition umbrella, which is being pursued by several area funding organizations.

- Supporting Community Organizing and Planning for a Just Transition

Some regional organizations have undertaken community-based planning work as part of larger pushes to achieve environmental justice through a just transition framework. These models require well-organized communities to guide the process to realize equity in both the process and outcomes of planning. Such efforts can be supported within the city to address multiple community stressors at once, and ideally, lead to new city-wide norms on how community needs drive city-level planning processes.

Closing Insights

Like many other cities, St. Louis GI planning has yet to confront the systemic racism shaping the city. For GI planning to be equitable and achieve justice, several interrelated areas of transformation must be addressed in terms of the guiding principles of plans, how they are written, by whom, and for whom. In this sense, grassroots organizations should be treated as the necessary creative assets required for the city’s positive transformation.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.