SEATTLE

Incorporated 1869

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

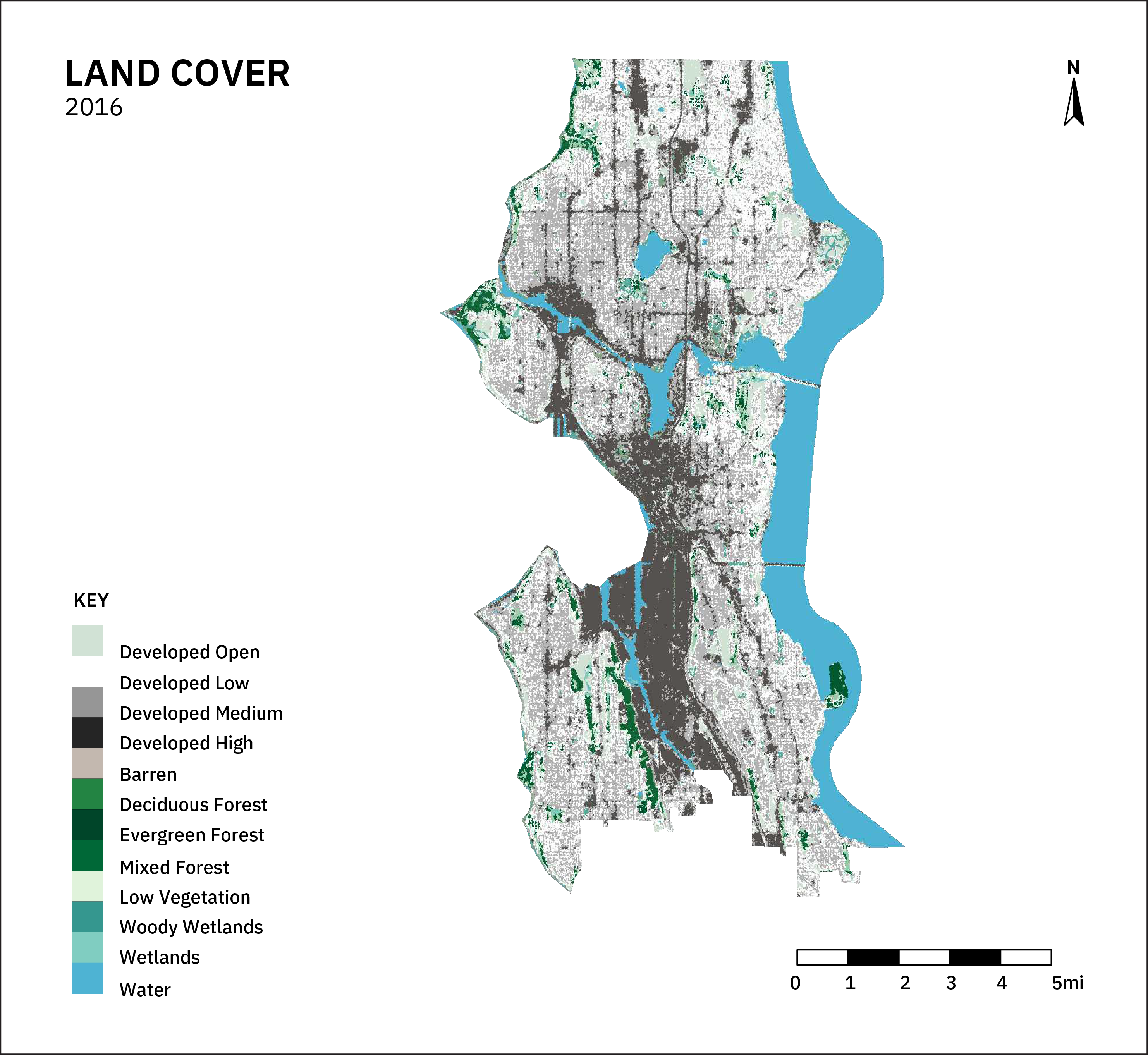

- 142.1 sq miles

- 708,823 Total Population

- 8,452 People per sq. mile

- 4% Forest cover

- Temperate Conifer Forests Biome

- 6.1% Developed open space

- $85,562 Median household income

- 6% Live below federal poverty level

- 58.1% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 6.1% Housing units vacant

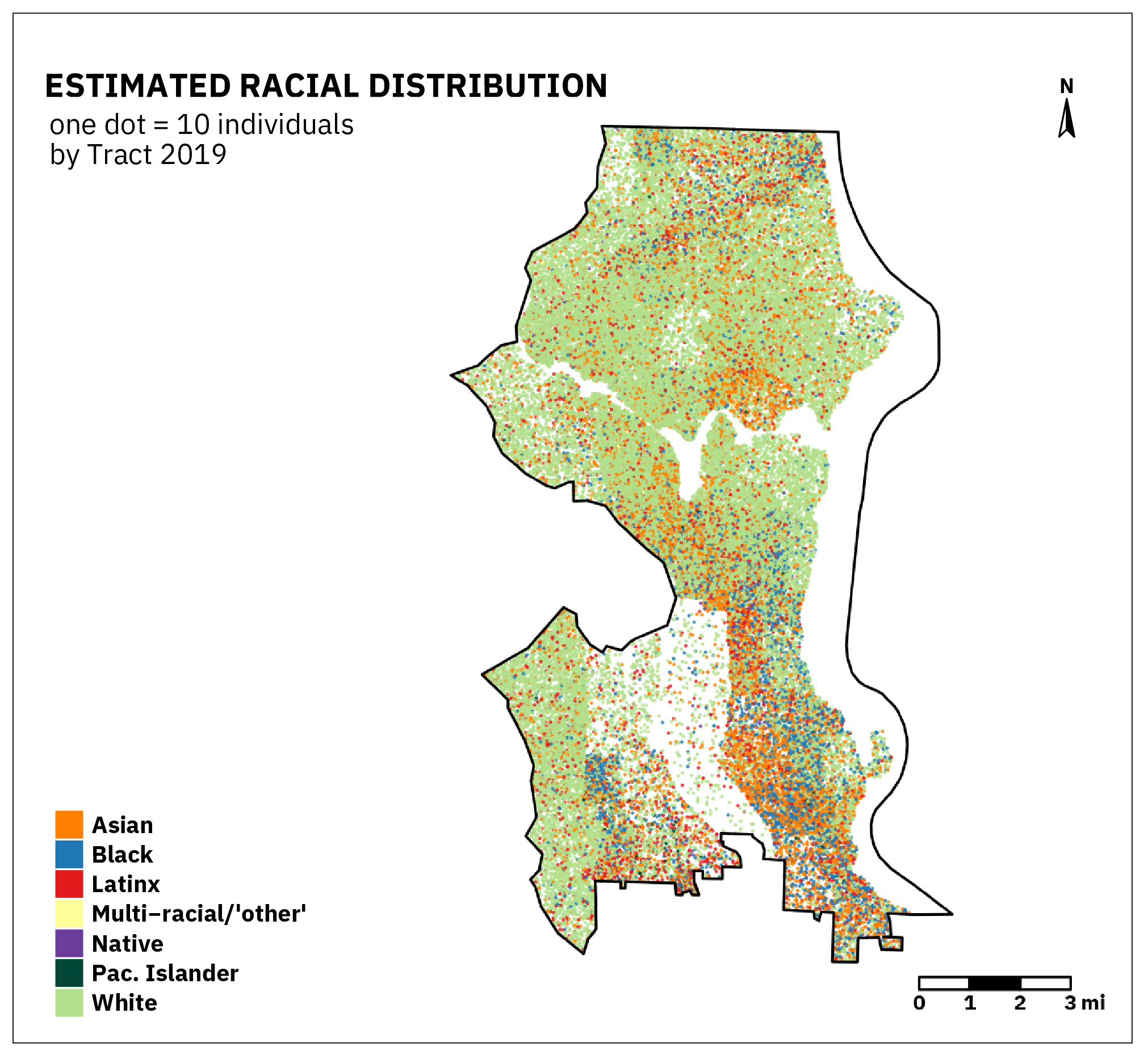

- 0.4% Native, 63.8% White, 7.2% Black, 6.7% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 15.3% Asian, <0.3% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The largest city in the Pacific Northwest, Seattle’s name and identity are inseparable from its occupation and dispossession of Duwamish lands. The Duwamish have maintained their presence in the city, and are an active force for environmental justice and ecological restoration. The city faces severe seismic risk and landslides. Climate-related challenges include sea-level rise, localized flooding, and increasingly severe droughts and wildfires during the region’s dry summers. The city also struggles with water quality deterioration and species loss caused by land use change and heavy industry.

The city has some of the lowest vacancy rates in the country. Housing prices have soared in recent years, and gentrification is a major concern of residents and area organizations. The city is still shaped by its legacy of purposeful segregation and racial discrimination. Vibrant immigrant communities and place-based organizations continue to marshal people and resources in the struggle for equity and justice.

Green Infrastructure in Seattle

We scanned numerous documents pertaining to green infrastructure in Seattle, finding six current plans relevant to our analysis. These included the city’s extensive stormwater management strategy written for compliance with Clean Water Act regulations. The city also has a dedicated GI Implementation Strategy, and the city’s GI programs are supported by its 2035 Comprehensive Plan. All of these plans focus on stormwater management.

GI strategies in Seattle utilize a broad range of ecosystem elements, hybrid facilities, and materials and technologies. Green roofs, rain gardens, and cisterns are integrated into blue-green corridors of trees, bioretention, and other stormwater management features.

The functions of this nascent system focus on a range of environmental and technological services. Hydrological functions are preeminent, focusing on infiltration, retention, flow attenuation, and evapotranspiration, along with pollutant removal and combined sewer overflow reductions and general drainage system performance enhancement.

Seattle GI plans did not articulate the benefits of GI within their GI definitions.

Key Findings

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan focuses on equity and addresses all ten dimensions within our equity screen, albeit inconsistently. The remaining 5 GI plans weakly address the concept, although they take some steps to be inclusive in their planning. The GI Strategy emphasizes addressing environmental justice issues through GI, but focuses on a ‘value added’ distributional approach that does not confront the underlying causes of inequity. Many opportunities exist to improve the equity of Seattle GI planning.

33%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

33%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

17%

define equity

66%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

17%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

17%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Seattle through Maps

Seattle is an exceptionally dense west coast city, constrained by its location on a near-peninsula bordering Puget Sound. Vacancy rates are very low overall, though are quite high both in the upscale downtown areas and in some working-class communities bordering industrial zones.

The city is racially segregated with minoritized communities residing south and north of the urban core. High levels of city-wide rent burden are clustered in the north and south of the city as well as the university district. These neighborhoods have much greater racial and ethnic diversity, mirroring ethnic and racial inequalities in income, although overall rates of poverty are some of the lowest in the country.

How does Seattle account for Equity in GI Planning?

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan provides a working definition of equity and attempts to address the concept in each of our ten equity categories. However, other stormwater and GI-specific plans inconsistently address equity issues. A welcome emphasis on justice does not meaningfully translate into strategies to protect residents from housing displacement, or have non-property owners capture the value of GI investments.

Envisioning Equity

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan has a fairly robust framing of equity and justice issues along with a functional definition that emphasizes community involvement in decision making processes, relationships, and outcomes. However, definitions and discussions of equity and justice are largely ahistorical and do not discuss the underlying causes of inequality in the city.

Procedural Equity

Seattle GI plans commit to fair treatment and community inclusion in decision making, guided by Seattle's Comprehensive Plan policies. The language of these policies carries through to all other city GI plans, many of which mandate mechanisms for community inclusion and public comment. However, public comment processes are notorious for box-checking and not requiring substantive action on the part of planners, as communities generally comment after the majority of planning work has occurred.

The Green Stormwater Infrastructure implementation strategy solicited community input through three listening sessions. However, it did not provide clear documentation as to who was involved, what their involvement entailed, or how input from marginalized groups was solicited or obtained. Mechanisms for sustaining community involvement beyond planning also appear to be inconsistent. Finally, despite including statements that suggest that communities should be involved in design, no real procedures are elaborated to that end.

The one exception was in the City’s Long Term Control Plan, which discussed community engagement mechanisms utilized by the Seattle Department of Transportation for designing a community greenway east of Delridge Way. This does not appear to be a universally applied practice. The Comprehensive Plan commits to an integrated interdepartmental approach to implement community planning recommendations and makes very concrete asks of the community to be involved in the process. Yet, resources have not been dedicated to compensating community members for their involvement despite a commitment to securing ‘sufficient funding’ for that purpose.

While this community involvement policy has good intentions and commits to creating dedicated project committees for plan implementation ‘reflect[ing] the community's diversity,’ it is unclear how this diversity will be transparently documented, and who will evaluate the efficacy of these involvement mechanisms. The only real mechanisms for community-based evaluation of plans appear to be in the plan update process. However, if the plan creation isn’t procedurally equitable, it will not truly allow for corrective action. Otherwise, regulatory plans have specific water quality targets but do not include consideration of how infrastructure investments affect communities, aside from sewer rate increases.

Distributional Equity

Seattle’s GI plans vary in how they address the distributional dimension of equity. The Comprehensive Plan sought to manage a wide range of hazards with GI and mentioned the risks of displacement associated with GI projects. However, the plan did not address issues of why some populations have been made more vulnerable to hazards, including uneven exposure and consequences. The other GI plans examined focused solely on affecting the distribution of water quality issues, without examining their current inequities or relation to other urban hazards. In terms of the value added by GI, the Comp Plan identified numerous benefits and acknowledged that adding property value is potentially problematic, but did not articulate an anti-displacement strategy. The Comp Plan also failed to address the contextual nature of value, in that the same types of GI may be perceived very differently by different communities.

The GI Implementation Plan’s approach to addressing equity was very similar to the Comp Plan in terms of community inclusion and addressing distributional equity. The GI Implementation Plan explicitly sought to employ members of the houseless community in parks and GI facility maintenance but it did not address the deeper wealth inequalities that such a labor hierarchy reproduces. Like other cities, Seattle embraced a model of competitive grant funding for community-based projects. This shifts labor and accountability to NGOs, further entrenching a project-based funding cycle that can erode longer-term capacity for community organizing.

The Long Term Control Plan focused on improving water quality through cost-effective infrastructure investments that also affect the level of service and timeliness of construction. These water system-focused improvements, however, were seen as having many knock-on benefits by improving the health of the aquatic environment, which inverts the multiple-benefit paradigm. Other stormwater-focused plans emphasized GI impacts on water quality improvements but did not address multiple values or equity. Labor issues were largely ignored by Seattle GI plans, which often required volunteers to maintain GI facilities, and reproduced problematic incentives to engage homeowners in these efforts.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Seattle has large-scale and well-developed green stormwater infrastructure programs that have significant potential to address the city's numerous social equity and climate change challenges. Concurrently, the city has an existing environmental justice committee and agenda but those priorities are not effectively embedded in its current GI plans. Evolving existing EJ approaches to maximize their effectiveness will require a targeted transformation in existing planning processes and embracing a more integrative city-wide GI planning concept. To that end, we offer several concrete recommendations below.

Community Groups

Seattle has many community groups working on environmental justice issues. The city has also served as an inspirational center for labor organizing. Current plans expect community groups and NGOs to apply for competitive grants to implement community-scale green infrastructure. However, community groups and NGOs did not appear to be included in shaping current GI planning efforts. Opportunities exist for the city government to support these community groups in fulfilling the city’s regulatory obligations. Yet doing so respectfully, and in a manner that meets diverse community needs, requires care. Below we highlight several areas where community groups could advocate for transformations in current planning processes and outcomes.

1. GI Labor as Wealth Building Strategy

Given that the city’s programs for GI are weak on labor issues, Seattle’s robust organizing community could advocate for a more explicit equity-centered approach in the work of designing, implementing, and maintaining GI. Unlike other cities, the idea of a liveable wage has been mainstreamed and sets a more acceptable minimum for maintenance practices. Additionally, Seattle could focus on training GI professionals in the communities where GI practices are planned, along with other strategies for building community wealth. Securing routes to homeownership in marginalized communities, either individually through appropriate labor compensation, or through a public option, is the only way GI investments that increase property values can contribute to sustained wealth building rather than displacement.

2. Demand Operationalization of Equity and EJ Principles in City Planning

Given that there are existing resources dedicated to addressing environmental justice in the city, community groups should insist that current GI plans reflect the work of the EJ committee over the GI lifecycle.

3. Securing Dedicated Long Term Support for Community Greening and Housing

Seattle as a city has remarkably low rates of poverty compared to similar-sized metropolises, and yet, issues with houselessness persist and may not be reflected in official census statistics. The ongoing growth of the real estate market in Seattle leaves the most marginalized communities behind and excludes the majority of Seattle families. Community groups can advocate for a GI strategy that goes beyond competitive grant cycles and incentivizing GI installations for homeowners. Such an approach could focus on including genuinely affordable housing as part of GI-based redevelopment together with other strategies for greening in place.

Policy Makers & Planners

Seattle policy makers and planners acknowledge the need for GI to equitably address multiple challenges while considering long-standing environmental justice issues. These admirable goals may not be achievable with the concepts and strategies outlined in current GI plans. To support the equitable and sustainable management of Seattle’s ongoing growth, we offer several concrete recommendations to policymakers and planners below.

1. Genuinely Inclusive Planning

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan involved extensive outreach and survey activities in its initial stages. However, discontent over how planning occurs in the city is persistent and vocal, even with the displacement of many marginalized groups out of the city and into the suburbs. Current plans need to meaningfully involve residents in designing, implementing, and evaluating the efficacy of city policies and programs meant to achieve plan goals. Think of this as equitable planning 2.0...getting off of the drawing board, out of the document, and engaging people in the work that the plan requires to achieve its vision.

2. Linking Housing and Environmental Justice

Seattle plans acknowledge the relationship between infrastructure investment, green improvements, and the potential for displacement. And yet, current plans have no mechanisms in place to address these issues. Proven strategies, like taxes on luxury development (which have some of the highest vacancy rates in the city), building infrastructure for genuinely mixed-use communities, and including housing provisions in bond measures and city spending on green improvements are some of the strategies that could be drawn upon. The city’s South Park neighborhood exemplifies many of these tensions. It is time to take action and heed resident demands for affordable housing and the curtailment of upscale development.

3. GI beyond the Stormwater System

Despite having a park system that appears to be one of the more equitably distributed in the country, Seattle plans do not appear to articulate a systemic vision of green infrastructure across the city. While parks, green stormwater planning, transportation, and built-environment design may seem ‘naturally’ siloed, each domain has profound influences on the others. Seattle planners and policy makers can look beyond the regulatory confines of the EPA, and like other cities, embrace a more integrated approach for GI system planning to realize numerous benefits from multi-functionality.

Foundations and Funders

Seattle GI plans have established a process for community groups to apply for GI project funding. Foundations and funders can support community organizations in building capacity to plan for cohesive, intersectoral GI projects that address the entwined concerns of housing and a healthy urban environment.

- Supporting Community Organizing for Intersectoral Environmental Justice

Numerous organizations working on environmental justice are already well-positioned to further a just approach to GI at the community project scale. However, foundations and funders could prioritize projects that build longer-term capacity in communities rather than just single installations and mitigate the gaps in Seattle GI planning around implementation, design, and evaluation. Two key needs are for community-based evaluations: (1) existing city approaches, and (2) implementation of strategic policies around housing affordability and community wealth-building in the face of large-scale speculative real estate investment.

Closing Insights

GI planning in Seattle has many promising avenues for greater inclusivity to achieve just outcomes. Grassroots communities should continue to advocate for a more robust conceptualization of equity in city planning that includes participation and community leadership through plan implementation and evaluation. City policy makers and funders can support communities in these efforts, by valuing community labor, and creating institutions for community ownership of GI. Ultimately, Seattle must address its historical legacies and present inequities if it is to heal its relationship with the land and water it has occupied, and people it has displaced to bring itself into existence.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.