AUSTIN

Incorporated 1835

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 327.4 sq. miles

- 935,755 Total population

- 2917 People per sq. mile

- 24.2% Forest cover

- Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands

- 17.4% Developed open space

- $67,462 Median household income

- 9.6% Live below the federal poverty level

- 61.3% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 8.5% Housing units vacant

- 0.2% Native, 48.3% White, 7.4% Black, 33.9% Latinx , 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 7.5% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

Austin occupies lands of several Native Nations including Apache and Comanche peoples who were forcibly removed from their homelands without compensation. Since its incorporation in 1835, Austin has experienced continuous growth of settler populations and has rapidly grown in recent years. Austinites enjoy a city with an abundance of open spaces that are relatively well connected.

Rapid growth has come with its costs, skyrocketing housing costs cause a majority of renters to face severe rent burden. Floodplain development and climate change pose challenges for equitable risk management of floods, heatwaves, fires, and drought. Overall, the city seeks more equitable access to green space and labor markets rooted in its creative economy.

Green Infrastructure in Austin

Austin utilizes a diverse array of GI concepts, especially in the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan, which provides an overarching framework for other plans including those addressing stormwater management, the urban trails network, the urban forest, and capital investments. However, GI is defined only in the Climate and Forest Plans.

Functionally, stormwater-related hydrological and built environment functions dominate the plans. However, the role that GI plays in the urban ecosystem, its ability to mitigate the urban heat island, and reshape transportation networks and options are also present within definitions.

Beyond those definitions, there are a variety of concepts reflected in a large diversity of GI types, which prioritize connecting ecosystems, farms, waterbodies, parks, trails, the urban forest, and river networks with several other GI elements.

Austin plans define the benefits of GI broadly, emphasizing its role in providing recreation, livability, and outdoor experiences while allowing for regulatory compliance, improving the design and performance of the built environment, and providing a range of environmental benefits.

Key Findings

Austin plans emphasize collaboration with residents, although affected communities have limited mechanisms to influence design, implementation, and evaluation. Most plans lack visions that extensively define equity and address justice except for the Comprehensive and Forest plans. The majority of plans address urban hazards and value but are mixed in if, and how, they consider the labor needs and opportunities of GI.

17%

explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

14%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

14%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

14%

define equity

14%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

0%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Austin through Maps

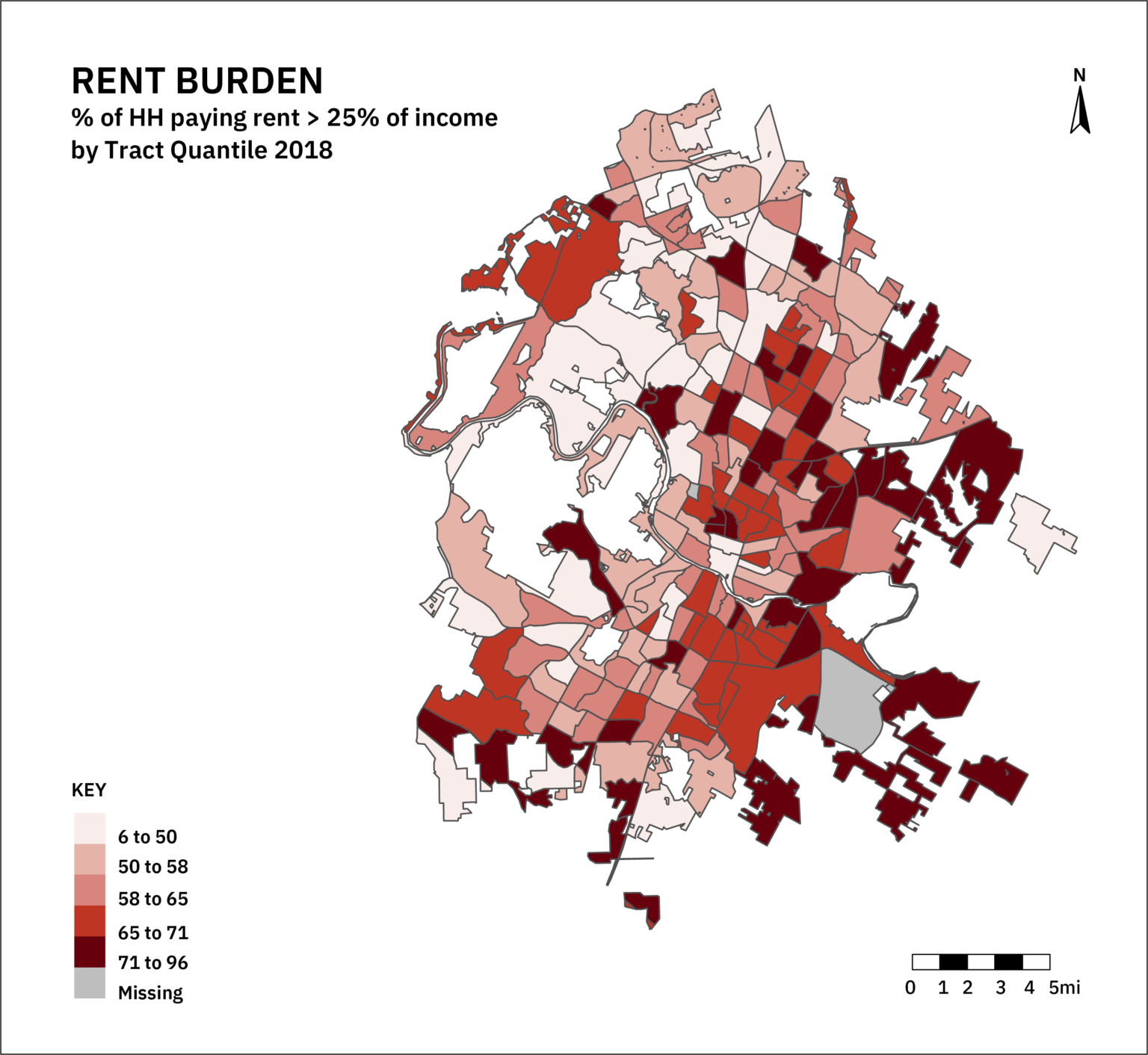

Austin has a complex and distributed urban form with a relatively low population density. Vacancy rates cluster in the center and south of the city, displaying an uneven relationship to the distribution of rent burden, which is generally high throughout the city and very high in some areas. Incomes are unevenly distributed, with western portions of the city having median incomes that often double those in predominantly Latinx neighborhoods in the eastern city.

How does Austin account for Equity in GI Planning?

With an emphasis on GI connectivity and values embedded within the planning system, Austin plans exemplify several best practices of inclusive planning processes, including specifying toolkits and assessment mechanisms for the multiple values of GI.

However, despite this emphasis on inclusive planning, evaluation mechanisms remain sparse, and the overall framing of equity concerns in plans has much room for improvement.

The City’s commitments to inclusive planning offer a strong foundation for process improvement and for collecting diverse perspectives on what would constitute equitable processes, visions, and resultant distributions of labor for the city as a whole.

Envisioning Equity

Only the Comprehensive Plan defines equity and does so in a universalist fashion that focuses on equality under the law and access to goods and services. It fails to address uneven risks, structural barriers, or variations in desired goods and services of different communities. The Plan addresses some historical injustices resultant from how the city has grown but lacks specifics. Otherwise, Austin’s plans provide weak framings of equity.

Procedural Equity

All plans examined contain some mechanisms for inclusive planning, with the Comprehensive and Forest plans committing to multiple avenues of community engagement. However, soliciting community input is inhibited by the current decision-making system which favors agency-led procedures and task forces. Communities have limited means for involvement in design and implementation, and even fewer for evaluating the impacts of plans. The Forest Plan is the exception to those conditions. It applies a community forestry framework that lists over 30 evaluation criteria, subject to annual review. It is unclear, however, how to raise social concerns not present in the existing framework.

Distributional Equity

Comparable to other cities, GI is understood as a means of addressing the distribution of hazards and values of the urban landscape. Most often, values are regarded universally and GI plans do not consider how they may differ between communities. Similarly, while a number of climate-related hazards are addressed by plans, limited work appears to have been done on their uneven social and spatial distributions. The Capital Improvement Plan seeks to study how improvements can be implemented in ways that do not disproportionately impact marginalized communities within the broader process of understanding the distribution of program costs and benefits. In terms of the distribution of labor, the Comprehensive Plan acknowledges that more equitable labor markets and economic structures are required to build intergenerational wealth. In other cases, volunteer and free labor appear to be vital to the realization of GI maintenance. Elsewhere, labor considerations of GI are absent.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Austin has a strong foundation of inclusive planning that can be readily built upon to improve the equity of GI plans and programs. Additionally, the diversity of elements considered within GI plans allow for a networked and city-wide planning approach delivering benefits and hazard reduction appropriate to the context. Delivering these services equitably will require more substantive mechanisms for community-led design, implementation, and evaluation. Given Austin’s sophistication in GI planning, it can improve upon its framing of equity concerns and address other historical and ongoing injustices in the city. Additional opportunities for supporting community wealth building center on the need to think creatively about built environment improvements, and fostering place-based industries that incorporate green technologies alongside improvements to the urban ecosystem. We expand on these themes below.

Community Groups

Many groups in Austin have rallied around social, economic, and environmental justice. Current GI plans seem open to their involvement during plan development, yet aside from the CodeNEXT revision process, mechanisms are lacking to meaningfully include communities in the design, implementation, and evaluation of GI programs and projects. Improving procedural equity in the city may be the way forward to tackle a host of intersecting social and environmental challenges. It is concerning that the potential for displacement from large GI investments is not discussed within city plans.

1. From Engaged Planning to Co-Design, Implementation, and Evaluation

Currently, plans addressing GI in Austin have limited means for community involvement in their design, implementation, and evaluation. Existing task forces and working groups, like the Code Next Task Force, the Flood Mitigation Task Force, and the Watershed Protection Ordinance stakeholder group provide a framework for limited citizen involvement, largely in an advising capacity. More robust and open mechanisms of place-based planning should guide such higher-level institutionalized efforts. There is a larger, more general need to move participatory planning from processes based on non-transparent mechanisms of garnering public opinion (e.g. surveys) towards more genuinely democratic models. Models that incorporate meaningful input from community members in the visioning and decision-making stages of urban futures planning.

2. Daylighting the Housing Affordability and Infrastructure Relationships

The Capital Improvement Plan’s proposed study on the distribution of costs and benefits of existing programs and procedures represents a unique opportunity to daylight the relationship between infrastructure expenditures and the cost of different types of urban form. Community groups can rally around such a process to demand better fundamental infrastructure and push for a broader accounting of how public monies affect the distribution of urban amenities, land value, and the distribution of hazards.

3. Emphasizing Labor Equity Amidst Rapid urban change and systemic challenges

Currently, GI plans have limited appreciation of the role that large-scale greening efforts can play in generating well-paying jobs. Framing climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the context of rapidly rising housing costs can center the need for workforce development and upskilling that supports intergenerational wealth building.

Policy Makers and Planners

Austin has a robust and cohesive planning framework that includes a diverse array of green infrastructure types across the city Further, these elements are coordinated within the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan. The implementation of Austin’s planning projects appear to be supported by a large number of city agencies and coordinating task forces, but mostly lacks mechanisms for substantive public input. These formal coordinating bodies have the potential to significantly improve communication and joint implementation among city departments and appear guided by the city's comprehensive planning. However, equity concerns remain poorly articulated and framed, and this is reflected in incomplete mechanisms for community involvement in the processes of creating and enacting plans.

1. Thinking Deeply about Equity

Austin’s GI plans do not define equity or justice in meaningful ways. Additionally, the overall framing of equity is nascent or problematic, if not wholly absent. While the Comp Plan and Forest Plan have robust inclusion mechanisms, there appears to be a limited understanding of equity issues within the plans, overall. For example, despite acknowledging that the “...way Austin has grown has increased alienation and unevenness”, the current Trails Plan focuses on connecting existing destinations. Other areas do not receive attention under this plan. Importantly, community input is factored in as only 12% of the overall weighting criteria for new trail creation. However, much can be done to think through what equity means in the context of GI planning using existing toolkits and other sources references (including this study).

2. Power Sharing

Austin should be commended for assigning clear responsibilities to city agencies responsible for GI implementation. However, implementation rarely involves affected communities. There are few, if any, mechanisms for community input on evaluating and course-correcting GI programs that may bring negative impacts to residents. Ceding power to affected communities outside of the normal electoral process is an important and necessary step for policymakers. GI programs are often long-term and spanning multiple administrations. Thus putting procedures in place that grant affected communities input and control over city agency programs and projects should be a priority.

3. Embracing Labor Innovation

There are significant opportunities to more explicitly examine the distribution of labor required for the urban transformations outlined by Austin’s GI plans. While the Comprehensive Plan lays out a framework for building wealth in marginalized neighborhoods through more equitable distributions of high-value labor, it does not link this goal to the city's green infrastructure programs. Perhaps this is not surprising, as both the Watershed Protection Plan and Urban Forest Plan explicitly seek to use volunteer labor for GI installations and maintenance as a way of keeping costs down.

Foundations and Funders

Austin’s Comprehensive Plan borrows a robust Green Infrastructure definition from the Conservation Fund (p 151) and thus appears to rely on non-profits for core aspects of its GI programs. However, non-profit or foundation support appears to be limited in city initiatives. The Urban Forest Plan in particular outlines a strategy of assigning a monetary value to GI to make the case for its expanded implementation. However, how monetary values are arrived at remains poorly specified, with limited means of accruing to residents or public budgets. In collaboration with existing partners, such as the Trust for Public Land, more nuanced evaluations of value recapture may be necessary to influence the overall austerity mindset presented in Austin’s GI plans. We recommend three concrete avenues to do so.

1. Support Research on Transformative Funding Mechanisms

There is no reason a city growing as quickly as Austin needs to have an austerity mindset. Real estate values have been skyrocketing, and the city continues to experience vibrant growth in population and economic activity. The principal challenge is to translate this growth into more equitable city government expenditures. If the city government is unwilling to explore creative and transformative solutions to GI funding, private and non-profit funders can fill this gap temporarily by investing in community capacity to articulate and plan for transformative funding mechanisms such as public banks, cooperative housing institutions, and neighborhood-level value recapture of GI improvements.

2. From Opportunities to Community-Led Programs for Redesign

The Austin Comprehensive plan explicitly states that it will seek opportunities to align water, waste, and energy conservation initiatives. This type of integrative thinking is noteworthy and offers a path to link siloed areas leading to greater sustainability. Water and stormwater, waste, energy, food, and transportation can be integrated through urban redesign. Integrating such diverse program areas will require empowering communities to make holistic and transformative shifts in these core urban systems. Thus city agencies could and should partner with funders to explore opportunities to create community-led deep redesign efforts that tie together these transformations rather than leaving them as top-down initiatives to be decided by city agencies.

Closing Insights

Equitable Green Infrastructure in Austin will require enacting the visionary and transformative concepts of GI in Austin’s plans through a more elaborated planning life cycle that allows for community-based implementation and evaluation. Austin has emerged as a leader in conceptualizing GI, and yet, foundational work remains in building community capacity to steer the future of the city through existing planning processes.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.