LOUISVILLE

Incorporated 1778

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 275.2 sq miles

- 617,032 Total Population

- 2,343 People per sq. mile

- 8.6% Forest Cover

- Temperate Broadleaf and Mixed Forests Biome

- 17.2% Developed Open Space

- $51,307 Median household income

- 11.9% Live below federal poverty level

- 58.5% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 10.6% Housing units vacant

- 0.1% Native, 65.6% White, 23.3% Black, 5.6% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 2.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The original ‘gateway’ to Western expansion, the City of Louisville occupies the homelands of numerous Native Nations, including Shawnee, Osage, and Cherokee peoples displaced by genocidal warfare and aggressive colonialism. Despite serving as a hub of economic opportunity for free Black folx before and after the Civil war, Louisville remains a highly segregated city. Recent waves of infrastructure investment intersect with legacies of urban renewal, highway development, and redlining all continuing to shape the city. In addition, the city has been impacted by numerous historic floods presently exacerbated by watershed development, climate change, and overwhelmed infrastructure systems.

Over the last decade, the city has struggled to reinvent its waterfront and downtown areas and has significantly expanded its highway system. Like many other cities, economic growth has been highly unequal, and current calls for justice center concerns over housing and policing. The city has a long, complex, and problematic history of award-winning parks and open space planning, significantly shaped by Frederick Law Olmsted.

Green Infrastructure in Louisville

Louisville has numerous beautiful green spaces, including the Olmsted-influenced city park system and other parks connected through the Loop plan. The city has made large investments in flood infrastructure near the Ohio river and seeks to address rainfall runoff induced flooding. Yet, the concept of Green Infrastructure does not feature prominently in Louisville plans. City of Louisville plans focus primarily on the health benefits of GI and, in some cases, GI elements were seen as providing ecological functions and improving the performance of the built environment.

Two plans address the GI concept. The Sustainability Plan defines GI as a key part of the city’s infrastructure systems with elements that include trees, bioretention facilities, and green roofs. The Louisville Loop plan refers to integrating GI into plans for trail and path connections but does not define the term Green Infrastructure. The regional Metropolitan Sewer District manages an extensive GI program but the regional utility’s plans and compliance mechanisms were outside the scope of this analysis.

Key Findings

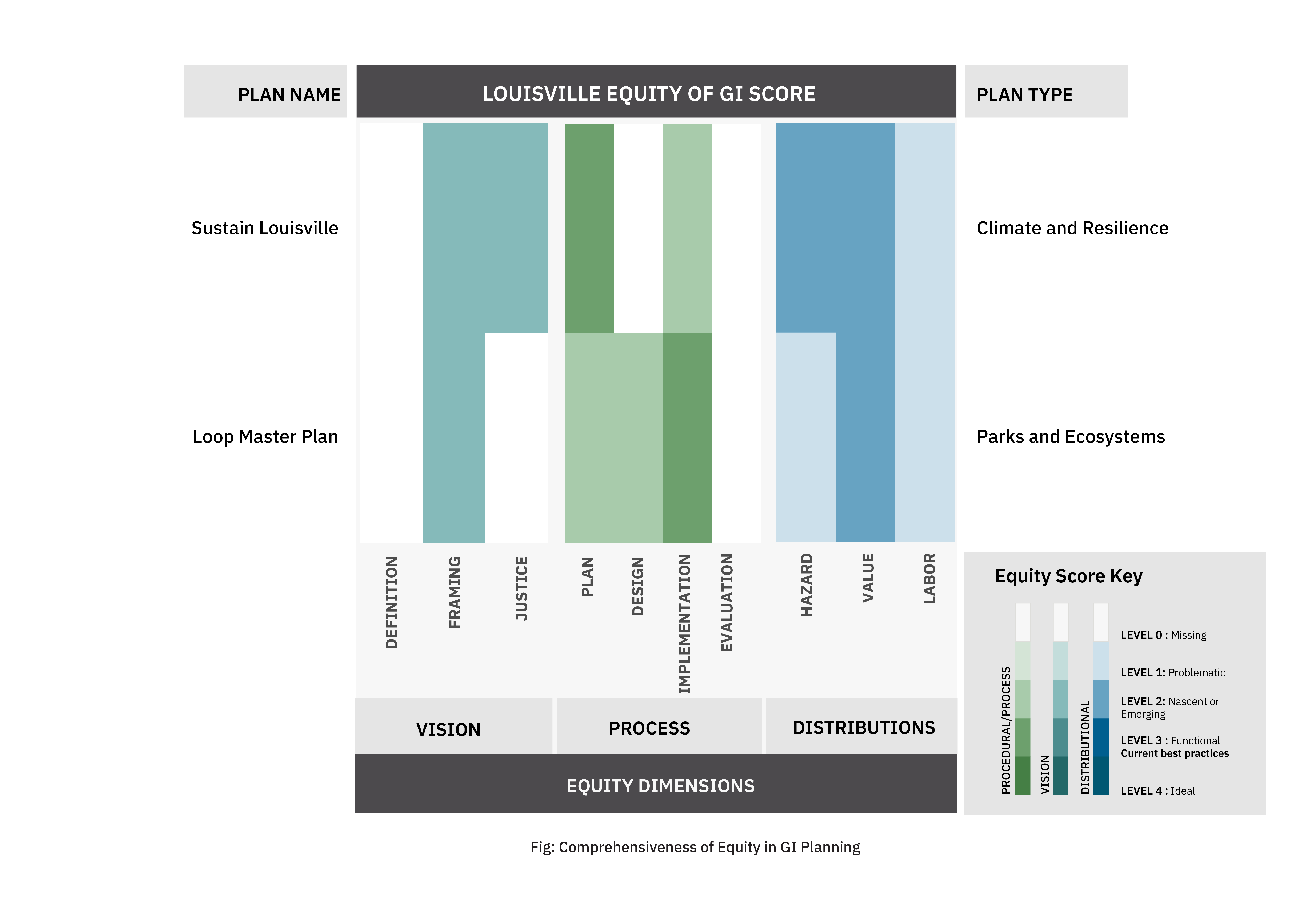

Equity is sporadically referenced but not defined in Louisville’s GI plans. While the Louisville Loop and Sustainability Plans seek to incorporate multiple equity concerns framing the visions for GI, there are significant procedural gaps in involving communities in design and evaluation. Further, distributional dimensions of equity are problematically addressed.

50%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

50%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

50%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

50%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Louisville through Maps

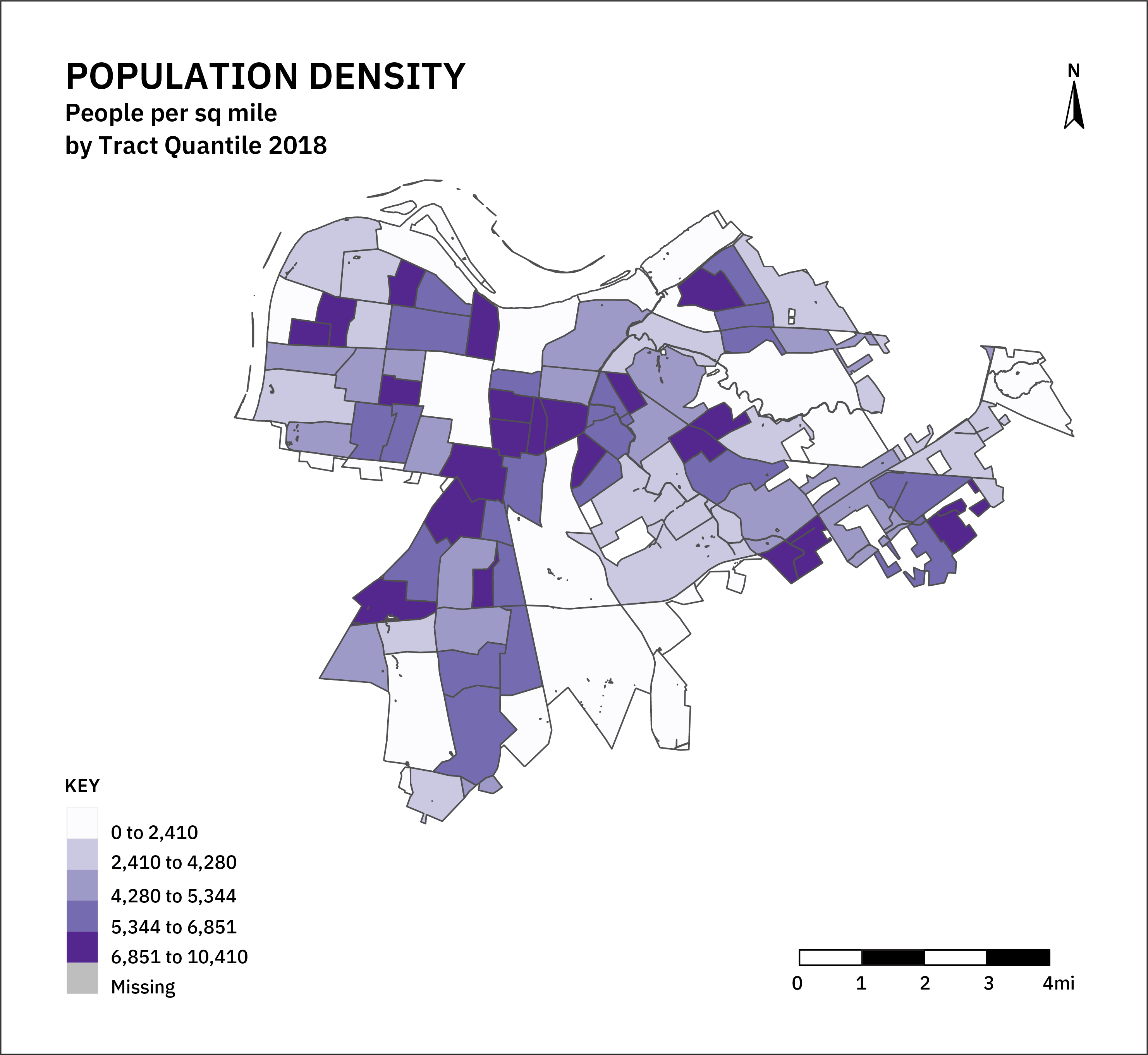

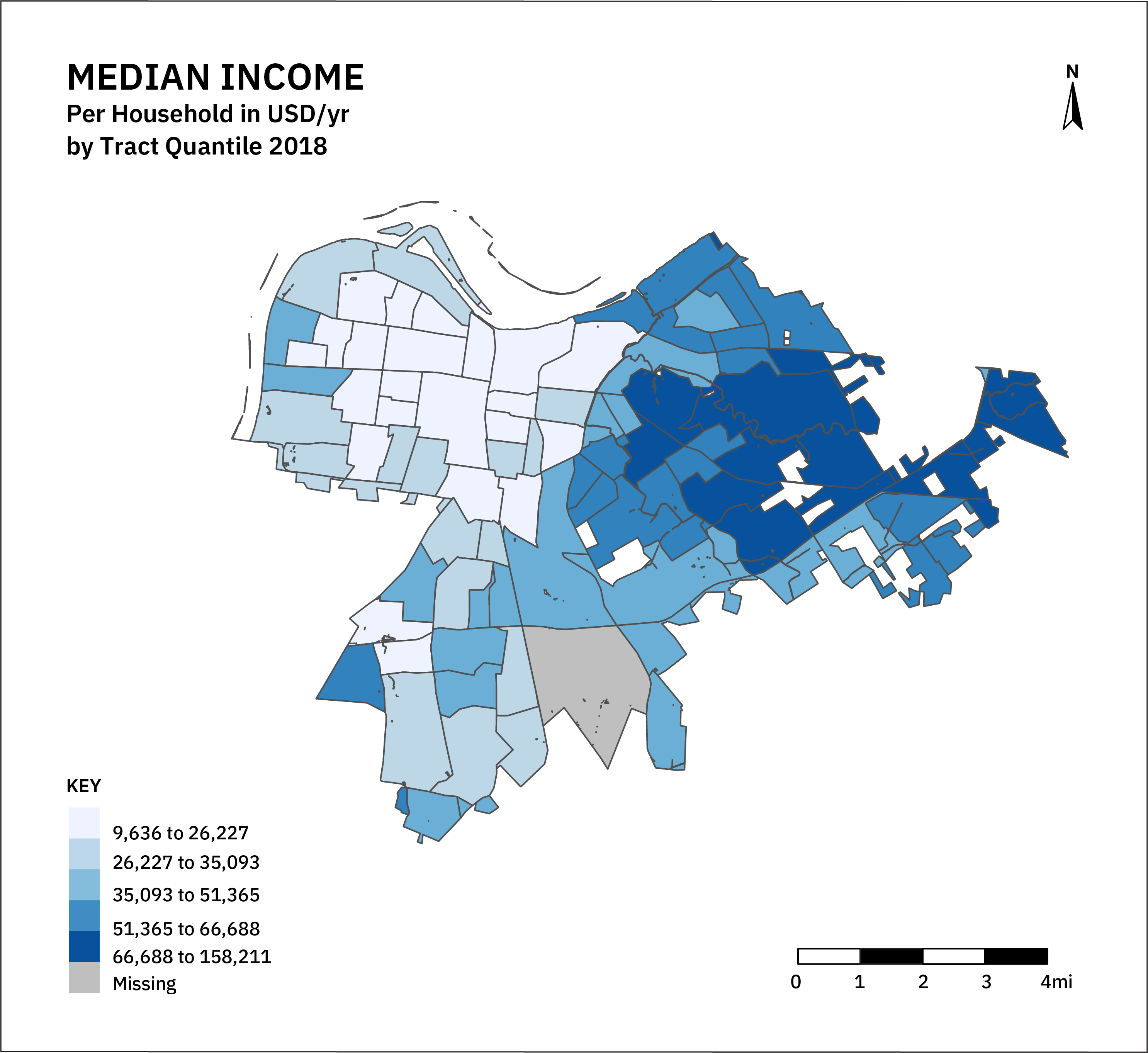

Louisville remains a highly segregated city by race and class. Most of the city is composed of low-density housing, although some historic neighborhood centers and the urban core have high population density. The impacts of redlining and other forms of targeted disinvestment can still be seen in the distributions of vacancy, income, and rent burden, all of which are highly correlated with race. The low density of the city provides for significant greenspaces, although distributions are highly uneven.

How does Louisville account for Equity in GI Planning?

Louisville plans do not robustly consider equity, with several dimensions completely unaddressed. Like other cities, intentions to involve communities in GI planning often fall short. While plans seek equitable distribution of the benefits of GI, there is room for improvement in how plans address the distributions of hazards and labor.

The Sustainability Plan makes notable efforts to discuss equity issues somewhat comprehensively but omits the procedural dimensions and ongoing demands for justice. Despite the intentions to address equity and justice in the Sustainability Plan, there is limited discussion of what either of those terms mean.

Envisioning Equity

Despite not defining equity explicitly, both the Louisville Sustainability plan and Loop Master Plans describe how their efforts will impact various dimensions of equity. The Sustainability Plan is more multi-faceted and emphasizes disparate access to environmental amenities, and uneven exposure to floods. However, despite hinting at environmental justice issues, there is no robust discussion of the sources of toxic hazards or of the social processes that created the present patterns of injustice. The Loop Plan embraces the need to improve public health and facilitate regional economic growth but largely focuses on marketing Loop initiatives to residents rather than successfully characterizing community needs and concerns.

Procedural Equity

Similar to sustainability plans in other cities, Louisville’s Sustainability Plan claims that, in the early stages of planning, it had multiple avenues of input from community stakeholders and a diverse set of city agencies over a year-long period. However, from the plan itself, it is not clear how this engagement occurred, or how concerns were addressed. The Louisville Loop plan refers to the need for publicly engaged design but does not specify how this will work and did not appear to be created through a robust public engagement process. The plan was written by a consortium of city agencies, environmental groups, and development interests, with no defined mechanisms for input from affected communities. Both plans emphasize outreach but approach this concept as a marketing strategy rather than an opportunity for meaningful inclusion. The implementation of non-city-led initiatives appears to rely on volunteer labor and stewardship without including any mechanisms for public evaluation of plan impacts.

Distributional Equity

The Sustainability Plan acknowledges the uneven distribution of hazards and seeks to use GI to manage heat, flooding, and stormwater concerns. However, there is no mention of the potential unintended consequences of hazard mitigation with GI. The Loop Plan, while stating that GI will reduce negative impacts on health, does not offer a causal connection between GI and hazard mitigation. Both plans seek to realize many values of GI, though offer very limited discussion of how these values must be contextualized with the specific needs of particular communities. The explicit dependency upon volunteerism in support of plan goals and initiatives, with no discussion of how this may be problematic, comprises the sole examination of labor for GI maintenance.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Racial justice issues have gained renewed prominence in Louisville since 2020. The city garnered national attention with the murder of Breonna Taylor in an area of the city that many say is being forcibly gentrified. At the same time, the administration of Greg Fischer has made headline commitments to addressing racial injustice, and as a member of the Government Alliance on Race and Equity, the city has made numerous commitments to addressing racism and injustice in plans and policies. Here we provide several recommendations for how community groups, city agencies, and funders could pursue strategies of equitable greening.

Community Groups

For many years, Louisvillians have been persistently working on racial justice and environmental quality issues. Existing campaigns for environmental and racial justice include the long-running efforts of REACT and KFTC. This same type of sustained community engagement will be required to successfully build meaningful inclusion and institutional transformation into current planning efforts for a city-wide green infrastructure network. After locating current gaps in community engagement practices, we identified two opportunities for community groups to shape the future of equitable GI in Louisville.

1. Demand Systemic Approaches to Environmental Issues

While current GI planning efforts do not appear to be a major concern for many community groups, it is clear that environmental hazards and injustice are. Since the city acknowledges that ‘green infrastructure is a critical component of the city’s infrastructure systems, residents can and should demand systematic approaches for greening existing polluting infrastructures and providing high-quality environmental amenities. This requires pushing for city-wide policies that target areas of the highest need for immediate improvements. Given founded concerns over gentrification, these approaches must be community-led and systemic. Community groups can build community-level capacity to effectively govern these types of transitions.

2. Call for Institutional Change

A high-quality environment, which requires investment in GI, is one aspect of environmental justice that mandates transformations in the way the City plans for its environment and infrastructure. The current plans do not provide meaningful mechanisms for the inclusion of impacted residents. Given a renewed national focus on racial justice, citizen groups can call for resources to be made available for the creation of residents’ planning councils that would shape all aspects of city life.

Policy Makers and Planners

In recent years City Government has committed to several racial justice initiatives, including a review of racism in Planning and Zoning and how the Land Development Code perpetuates racial segregation.

While the city has received credit for how it has pursued community-based development in the Russell Neighborhood, there are many criticisms within the community from long-standing residents who have felt left out or ignored as the community gentrifies, and who are continuing to fight for the right to emplacement. It is up to planners and policy makers to make space and provide resources for community groups to lead on visioning city redevelopment projects and to actively evaluate and govern outcomes of ongoing initiatives. The city’s legacy of high-quality public infrastructure requires both a guiding vision and accountability to those whom the infrastructure is supposed to serve.

1. Defining Equity and Justice

Current plans do not define equity or justice. A first step forward for city policy makers and planners is to form better connections with community groups working on racial equity and justice issues. Then, with local expertise, contextually define what equity and justice mean for urban planning in Louisville. While policy makers have made public statements and commitments, it is not yet clear how ideas of racial justice will be operationalized within city institutions. Adopting formal definitions of equity and justice that come from the community itself is one small but meaningful statement towards institutional transformation.

2. Equitable Governance of GI

Marginalized communities in Louisville feel they are not being heard and do not have control over city institutions that plan for their futures. The city can rebuild trust and faith by demonstrating that it not only listens to the concerns of residents but acts on them to transform practices and institutions. While many of the community concerns present in Louisville are broader than GI per se, one way that the city can demonstrably commit to wealth building in oppressed communities is by creating resident-based comprehensive planning that is connected to resources for implementation. Following our framework, these planning processes require financial commitments to community groups to lead the planning, subsequent design, implementation, and evaluation of policies, programs, and projects.

Foundations and Funders

Foundations and Funders have a historic opportunity to fund community groups in Louisville to demand restructuring of the city decision-making and funding apparatuses that implement city plans. Such restructuring requires deep deliberation among community members, followed by the experience of being heard and of seeing community concerns and aspirations translated into meaningful institutional change. Nonprofits and foundations in Louisville have already operationalized new models of funding community-based organizing to focus on within-community leadership. This turn towards increased representation is welcome, and yet, relying on representative forms of governance are inherently competitive and promote a mindset of resource scarcity rather than building collective power.

1. Building Collective Power to Shape Urban Futures

In light of current funding models, there are ongoing opportunities to fund forums to elevate the conversation around what democratic urban planning could be through community visioning and organizing. Knowledge from these forums would inform city programs tasked to help build resident councils. These councils would be designed to mobilize and support communities to engage in participatory planning and revitalize neighborhood-level governance. Already in the Russell Vision initiative, the limitations of a ‘community representative’ model of participation have become apparent, with competition-based resources leading to increased division within the community rather than a deliberative process about the collective future. However, public appetite for a better future remains strong, and if resources were made available for collective forms of decision-making, new strategies and avenues for more desirable urban futures may become apparent. Given the lack of community engagement mechanisms in Louisville plans, these require development from the grassroots.

2. Restructuring without Renewal

City plans for neighborhood renewal must grapple with the legacies and ongoing displacement of current and long-time residents to make way for improved urban environments. At the same time, exposure to toxic chemicals, air pollution, combined sewer flows, and wastewater treatment remain highly uneven and require a transformation of the physical environment. Historic planning pushed certain communities into undesirable areas. Can and should those areas be redeveloped? What do communities in those areas want?

The current combative stance between the administration and community activists indicates that many equity issues need to be addressed. However, without deeply restructuring current institutions, there is no reason to assume that equity and justice will take care of themselves. Further, addressing problem flooding and persistent environmental and social inequality requires restructuring the way that decisions are made within, and outside of, current institutions. Foundations and funders can play an important role in bridging the gap in transforming community-level decision-making in support of larger-scale institutional transformation.

Closing Insights

Equitable GI planning in Louisville suffers from a lack of clear conceptualization of either green infrastructure, or equity and justice. Numerous community groups are demanding transformative approaches and the beginnings of a funding ecosystem for coalition-based transformative work is emerging. It will take sustained effort on behalf of communities and funders, and sustained openness of those already in positions of power, to restructure urban governance in a way that makes equitable planning possible.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.