MIAMI

Incorporated 1825

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

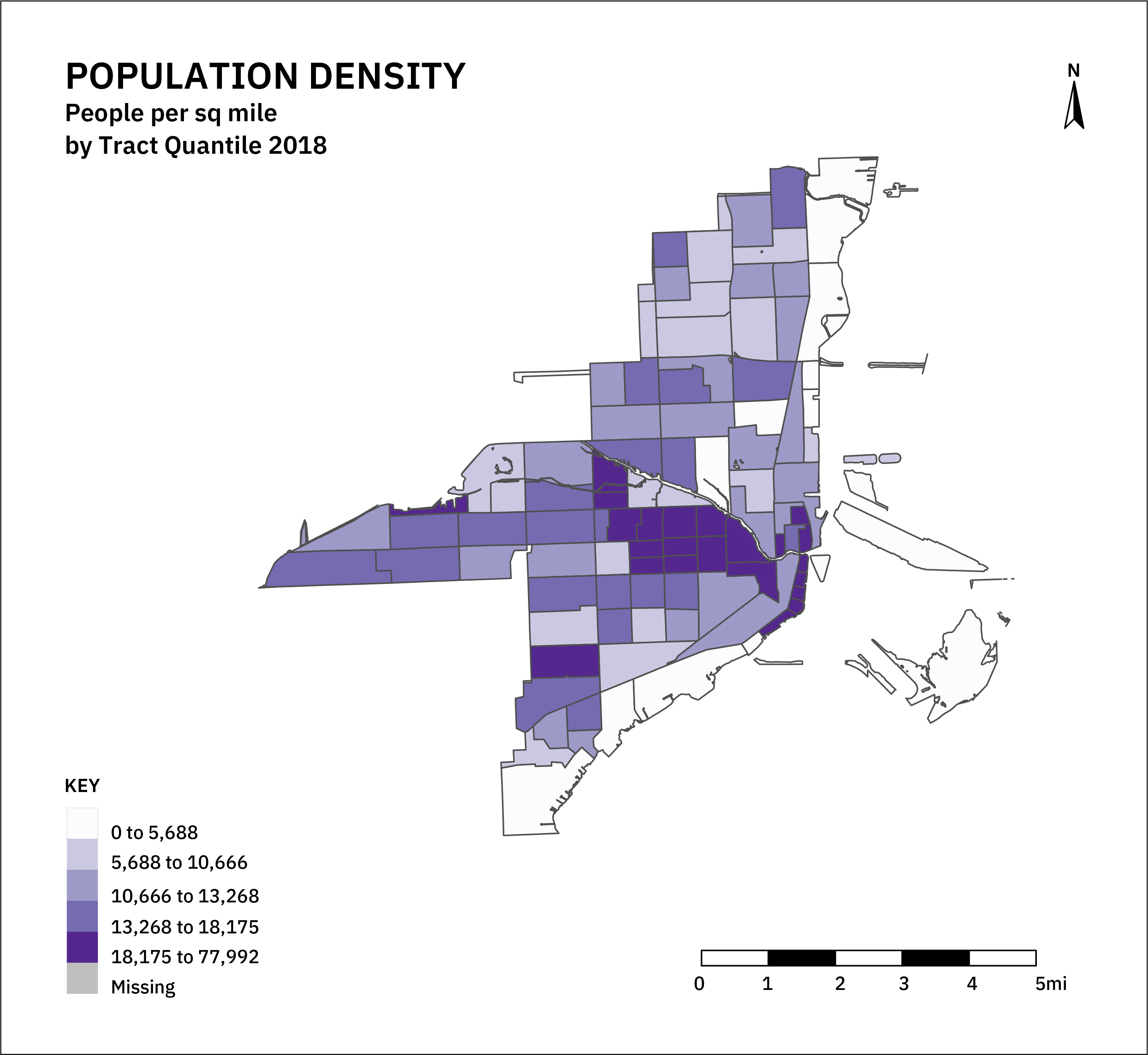

- 36.0 sq miles

- 36.0 sq miles

- 451,214 Total Population

- 12,535 People per sq. mile

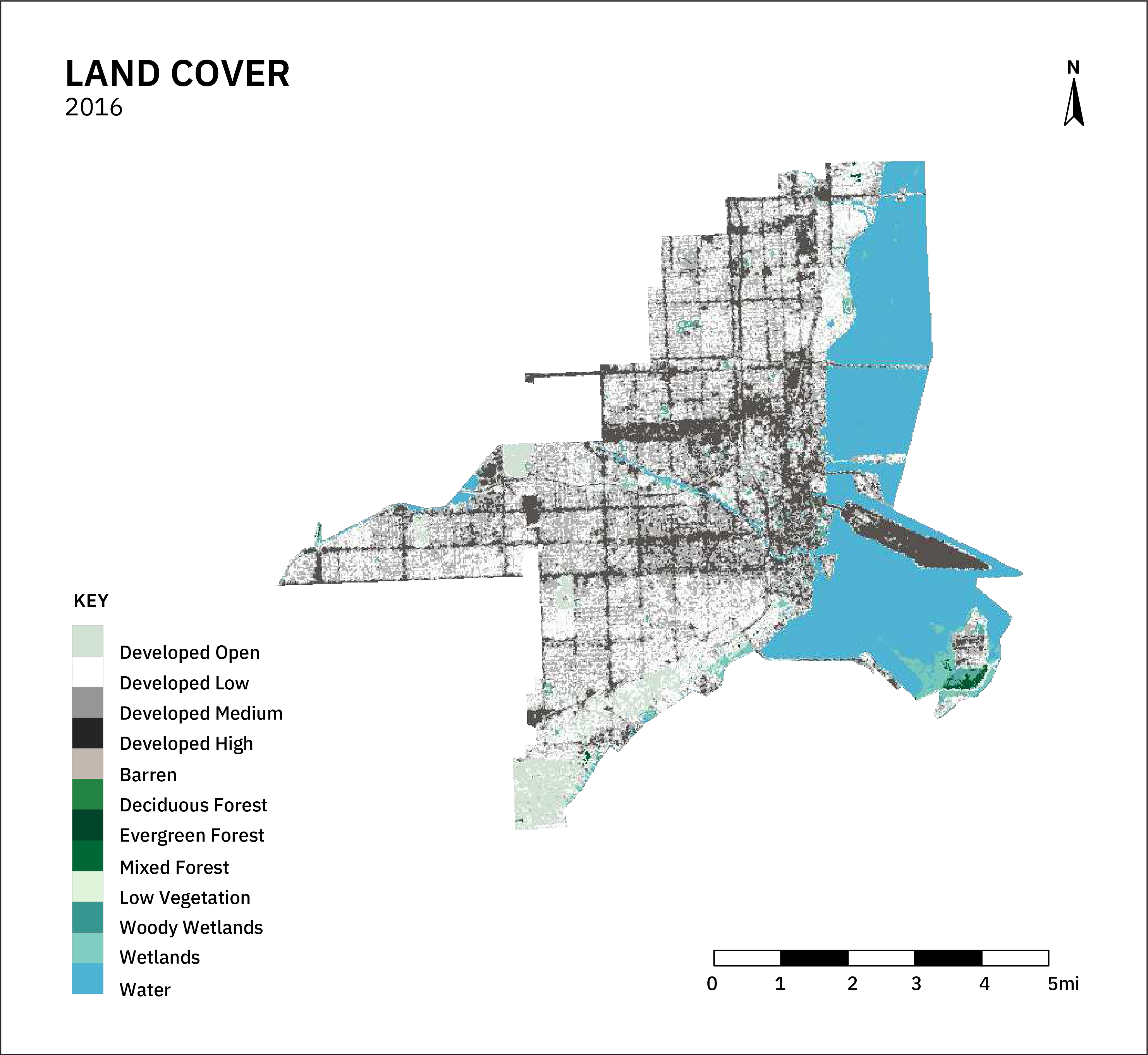

- 0.2% Forest cover

- Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forest Biome

- 6.8% Developed open space

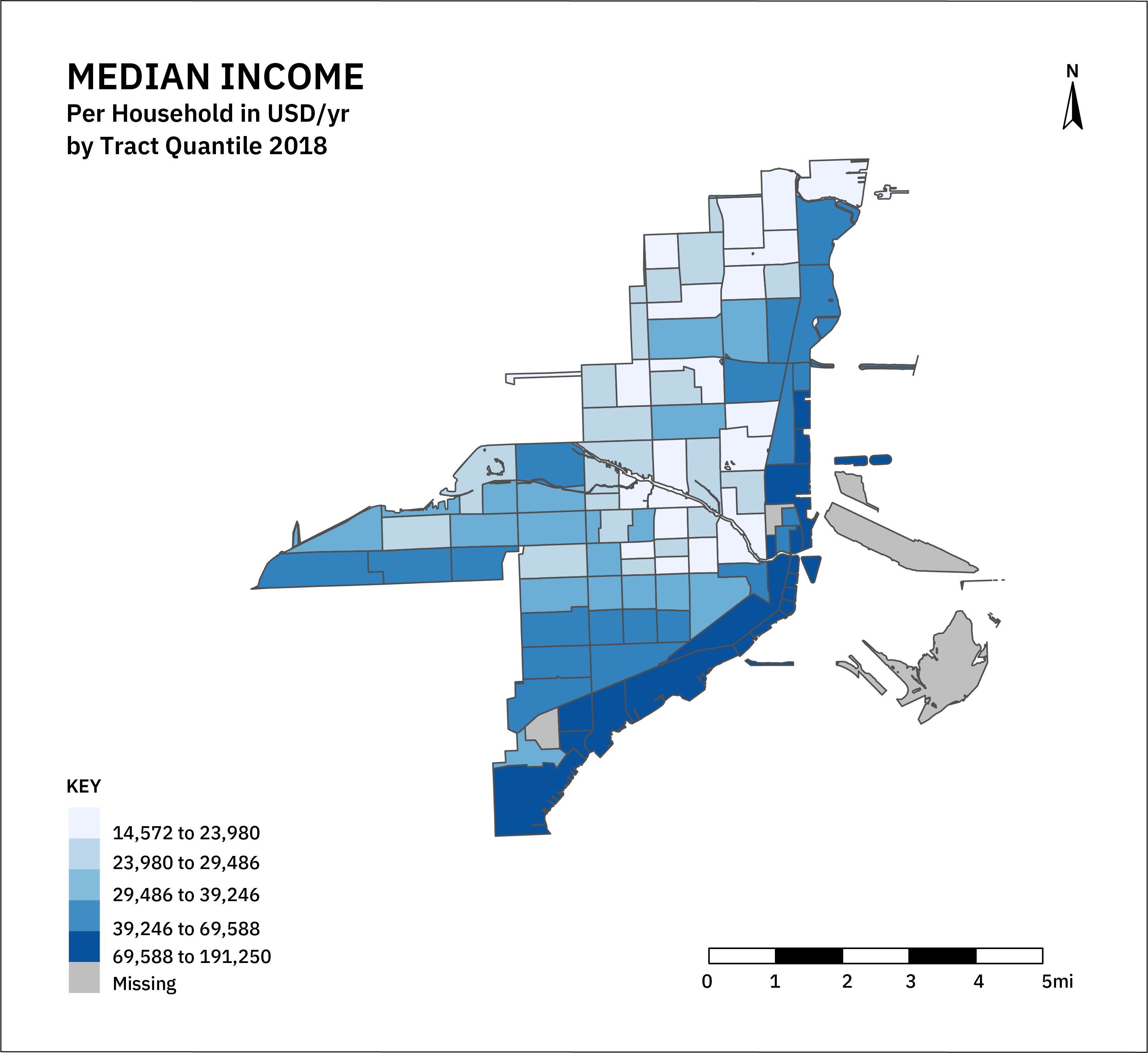

- $36,638 Median household income

- 20.2% Live below federal poverty level

- 75.9% Estimated rent-burdened households

- 15.4% Housing units vacant

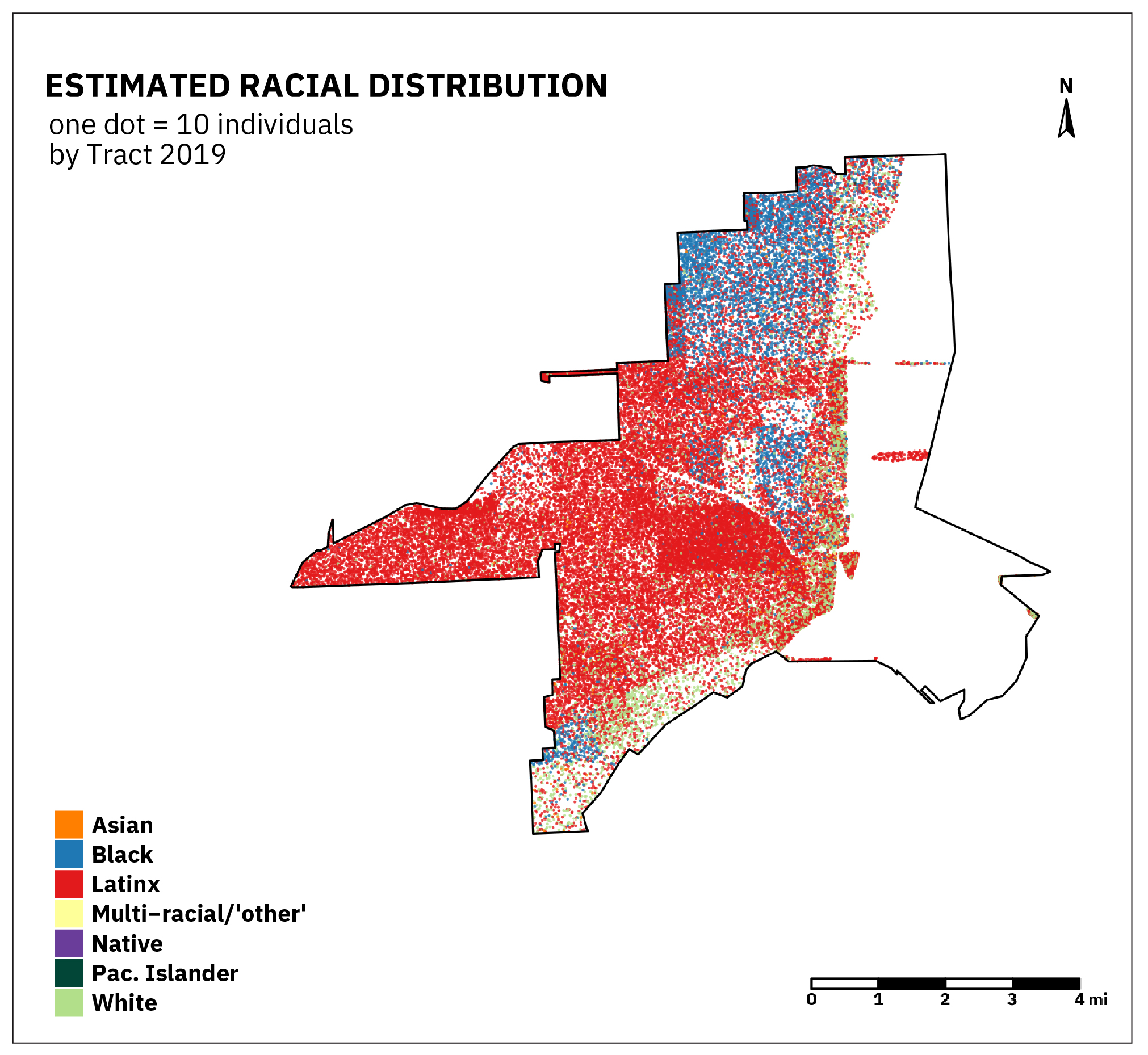

- 0.1% Native, 11.3% White, 14.4% Black, 72.7% Latinx, 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 1% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socio-economic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and Land Cover Data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

The City of Miami occupies the lands of several Native Nations including its namesake the Mayaimi people and has an important history of successful Seminole resistance to slavery and colonization. Not to be confused with Miami Beach, this predominantly Latinx city has become a hot spot of climate gentrification and climate justice. Despite increasing climate risks due to sea-level rise and an increasingly chaotic hurricane season, the city continues to experience booms in population and real estate investment with the majority of residents being rent-burdened. In combination, these forces appear to be accelerating the displacement of marginalized communities.

The city now regularly experiences daytime tidal flooding by ‘King Tides,’ which Miami Dade County, with the help of the federal government, has been addressing through large-scale stormwater programs, which fall outside the scope of this analysis. The city has invested significant resources in its park system to provide a verdant backdrop of the highly urbanized and dense city.

Green Infrastructure in Miami

In stark contrast to other cities focusing exclusively on stormwater infrastructure, Miami Green Infrastructure plans focus almost exclusively on creating a high quality and city-wide system of parks and urban canopy, through its Parks and Tree Plans.

Both the Parks and Tree Canopy Master plans refer to diverse and networked green spaces, engineered streetscapes, and ecological elements using a landscape concept of GI.

GI is primarily seen as fulfilling social functions, providing opportunities for gatherings, recreation, and building a sense of identity. The benefits of GI in Miami are defined across environmental, technological, and socioeconomic domains.

Plans recognize that GI provides numerous socio-economic benefits, assists with climate adaptation, and functions as a core part of the city’s infrastructure and urban fabric. The Climate Plan references the GI concept, yet it does not provide an explicit definition.

Key Findings

Miami GI Plans refer to equity and justice and yet fail to meaningfully define either. Despite this omission, the Parks Plan exemplifies some best practices in procedural equity. All plans are concerned with the distributional aspects of equity. However, weak framings appear to prevent a robust and contextual exploration of current distributional issues and how they could be addressed by planning.

100%

Explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

0%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

100%

seek to address climate and other hazards

66%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

0%

define equity

33%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

33%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Miami through Maps

The City of Miami is characterized by a dense urban core and a large degree of segregation in income and racial composition, reflected in high vacancy rates in neighborhoods with extensive luxury development. Rent burden is likewise highly unevenly distributed. Greenspaces, predominantly parks, are distributed fairly evenly around the city. Somewhat extensive mangroves and coastal wetlands line the city's southern coastline, and portions of the Miami river, as the coastline is otherwise extensively armored with hard infrastructure.

How does Miami account for Equity in GI Planning?

Miami City plans make admirable commitments to participation and addressing contextual uses of GI. However, no single plan in Miami addresses the dimensions of equity in our analysis, and visions of equity in plans are largely problematic. Mechanisms for procedural equity were inconsistent across plans. Distributional elements are discussed, but not robustly analyzed.

No plans define equity or justice and framings are generally universalist with no mention of potential adverse impacts of proposed activities.

Planning processes are highly centralized, with appointed commissions and city staff primarily responsible for implementation and evaluation. The exception is the Parks Master Plan which considers the needs of diverse user groups of parks, as well as the contextual value of parks within a city-wide green infrastructure system providing multiple functions and benefits. It also utilizes extensive outreach surveys for planning, design, and evaluation, although this process is overseen by an appointed commission.

Plans inconsistently address distributional aspects of hazards, values, and labor. There is a mixed emphasis on climate-related hazards and the role that GI plays in managing them is not always clear. Like other cities, plans seek volunteer labor to realize GI.

Envisioning Equity

The City’s Parks Master plan robustly frames the contextual value of Parks to diverse urban communities, explicitly addressing the value of parks as part of a city-wide system of green infrastructure that provides diverse functions and benefits. In the Parks Master Plan, like the Urban Tree Plan and the City’s Sustainability Plan, GI is seen as providing universal goods. The plans do not unpack the complex role of public realm investments in housing displacement or other unintended consequences. The Climate Action Plan states that it will address environmental justice through transportation system redesign, but does not elaborate.

Procedural Equity

Mechanisms for community engagement over the planning lifecycle are inconsistent. The Parks Master plan commits to community inclusion throughout the planning lifecycle, including evaluation, but provides limited documentation of what communities were involved, instead relying on new city-wide commission and survey instruments. The Tree Master Plan explicitly relies on input from the same Miami Green Commission and an Urban Forestry Working group, with unclear mechanisms of broader public participation, and no evaluative mechanisms aside from a proposed city-wide tree database. The Climate Plan acknowledges the need for community involvement but has no mechanisms or processes described, despite committing to a framework for tracking plan impacts.

Distributional Equity

The Climate and Tree Plans acknowledge the immanence of climate hazards, with the former discussing the region’s vulnerability and the latter focusing on tree mortality. The Climate Plan discusses the vulnerability of Southern Florida and sets in motion a process to identify vulnerable areas for use in other city plans. The Climate Plan, however, does not discuss how GI may manage those hazards. Further, the benefits of GI are largely absent from the Climate plan, which focuses on the benefits of transit-oriented development (TOD) and how sustainability benefits regional prosperity. The Climate Plan seeks to engage volunteer labor, especially with regards to managing GI in the face of climate change but does not discuss the inequities that may result from a volunteer-based system of maintenance and adaptation.

The Tree Plan sets in motion an analysis of the multiple values of an urban canopy but only proposes to do so through the City GREEN tool which reduces many values to economic and biophysical indicators. This plan fails to mention labor issues.

Parks planning seeks to provide contextual value to existing residents as well as a city-wide GI system.

The Parks Master Plan emphasizes how parks can improve the safety of transportation and improve water quality, but does not appear to address climate-related or other urban hazards. The Parks Plan commits to hiring a volunteer coordinator to enhance the network of ‘Friends of Parks’ groups, specifically targeting the need for more volunteer maintenance and engage in other forms of labor such as evaluating park performance and serving on advisory boards. Although the Parks Plan mentions the need for dedicated funding for these groups, it does not discuss the inequities embedded within such an approach.

No plans discuss the potential downsides to large investments in urban amenities or how they will be managed, nor do they robustly consider labor issues.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Miami Plans provide a basic scaffold for community-led planning of a city-wide green infrastructure network. Given ongoing initiatives to adapt to climate change in the city, especially those operating across federal and county levels, we provide several key recommendations to improve the equity of GI planning in Miami. We offer these in recognition that the most recent climate change adaptation plan fell outside the scope of our formal analysis.

Community Groups

There are numerous social and racial justice organizations working in Miami that can be engaged and supported in organizing communities to proactively lead planning processes addressing the intertwined crises of climate change, housing, and economic justice. While the City appears to have made great strides in connecting with community groups in park system planning and evaluation, much more needs to be done to activate Miami residents to address the intersecting climatic and social challenges faced by their communities.

- Rallying around a Just Transition Framework

Current GI plans in Miami generally seek to add amenities and GI features to the urban landscape. They do not acknowledge the processes that have led to the highly inequitable landscape of climate risk and socio-economic conditions. The most recent climate adaptation plan focuses on a broad GI strategy and will appear to have significant financial support from the federal government. Communities can rally around the idea of a Just Transition to make sure these funds support community-led planning and adaptation efforts, including economic transformation for climate change-associated jobs and building community wealth through city-wide GI programs.

Policy Makers & Planners

The City’s existing and emergent approaches focus on a citywide GI network, with the most recent climate plan integrating stormwater systems with the urban canopy. This is an improvement over the existing landscape-focused approaches in the city’s parks and tree plans, though integrating infrastructure systems poses new sets of challenges. There is a risk of omitting the equitable processes developed in the park system plans in the city’s climate adaptation programs.

1. Integrate Emergent Climate Planning With Park’s System Planning

This plan omits the extensive work performed by the City’s Park department and may miss opportunities to expand the park system along with city-wide canopy, stormwater infrastructure, and shoreline projects. Given the enormous pending investments in climate adaptation occurring in the region, the city could take a more expansive and inclusive approach towards GI system planning.

2. Expand Community Based Evaluation Frameworks

The Parks Plan provides a workable framework for evaluating city initiatives which could be expanded to address the intersecting concerns above. Mandating and funding community engagement through the entire planning lifecycle, and including the lived experience of communities as a key metric of successful adaptation and GI implementation strategies, requires binding commitments from existing decision-making bodies.

3. Address Economic and Racial Justice in GI planning

Given large disparities in income in the city, building community wealth by compensating GI planning, design, and implementation is a viable strategy for supporting greening in place. Given the issues of housing displacement, the city urgently needs to restructure planning to meet the needs of existing communities. Such an approach would need to recognize the intersection between racial justice, housing displacement, and GI investments. This understanding remains absent from the most recent climate adaptation plan.

Foundations and Funders

Miami has a rich ecosystem and history of community organizing that can be supported by local and national foundations and funders. Existing Green Infrastructure plans highlight several areas for consideration.

1. Support Intersectional Organizing

Organizations working on greening and environmental justice, like Catalyst Miami, along with numerous other groups recognize the need to simultaneously address economic and environmental justice. Equitable adaptation and mitigation, pursued simultaneously through a Just Transition framework, require dedicated, and often long-term, funding for community organizing, especially in the face of housing displacement. Given large disparities in income and significant rent burdens in the city, foundations and funders can contribute towards building community wealth by compensating planning, design, and implementation as part of a broader strategy for equitable greening in place. One that enhances existing community strengths and capacities for self-determined and just futures.

2. Building Participatory Governance From the Ground Up

Foundations and funders can invest in community-led planning processes to inform and transform how city agencies plan for city-wide GI and climate adaptation projects. Community-led initiatives to build new institutional processes for giving communities real power in GI and CCA decision-making could benefit from dedicated foundation support. Grassroots initiatives are necessary to balance power within existing large-scale initiatives to address climate resilience including the well-known Southeast Florida Climate compact.

Closing Insights

Miami’s rising climate challenges contrast sharply with its ongoing growth. Massive public and private investments in green infrastructure as part of city-wide adaptation programs can build off of existing processes that involve communities in city-wide parks and green infrastructure planning. Building community wealth will require recognizing communities as experts on the immediate challenges they face.

Resources

A public access repository of all the 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.