BALTIMORE

Incorporated 1729

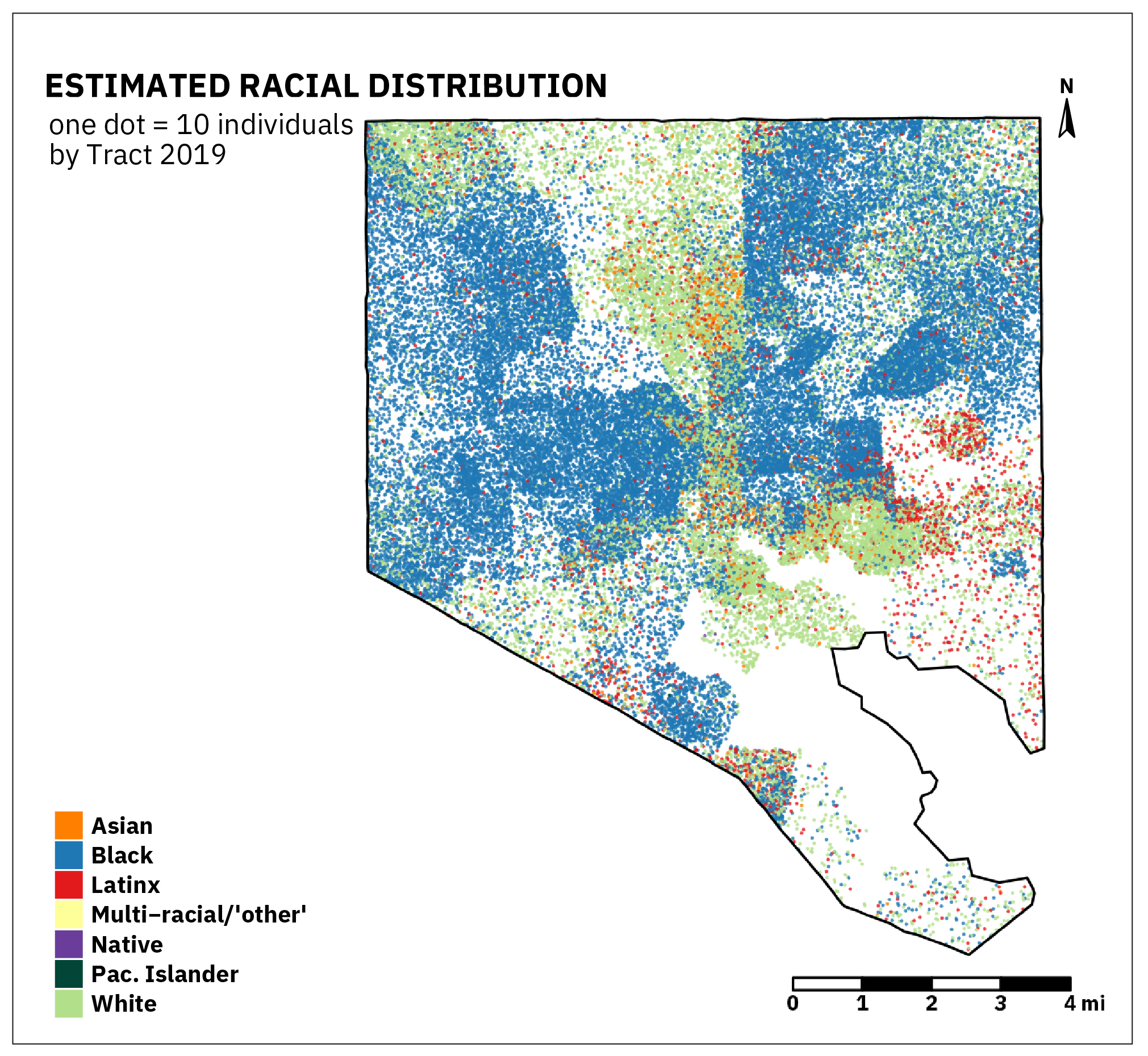

CITY DEMOGRAPHICS

- 92.1 sq. miles

- 614,700 Total population

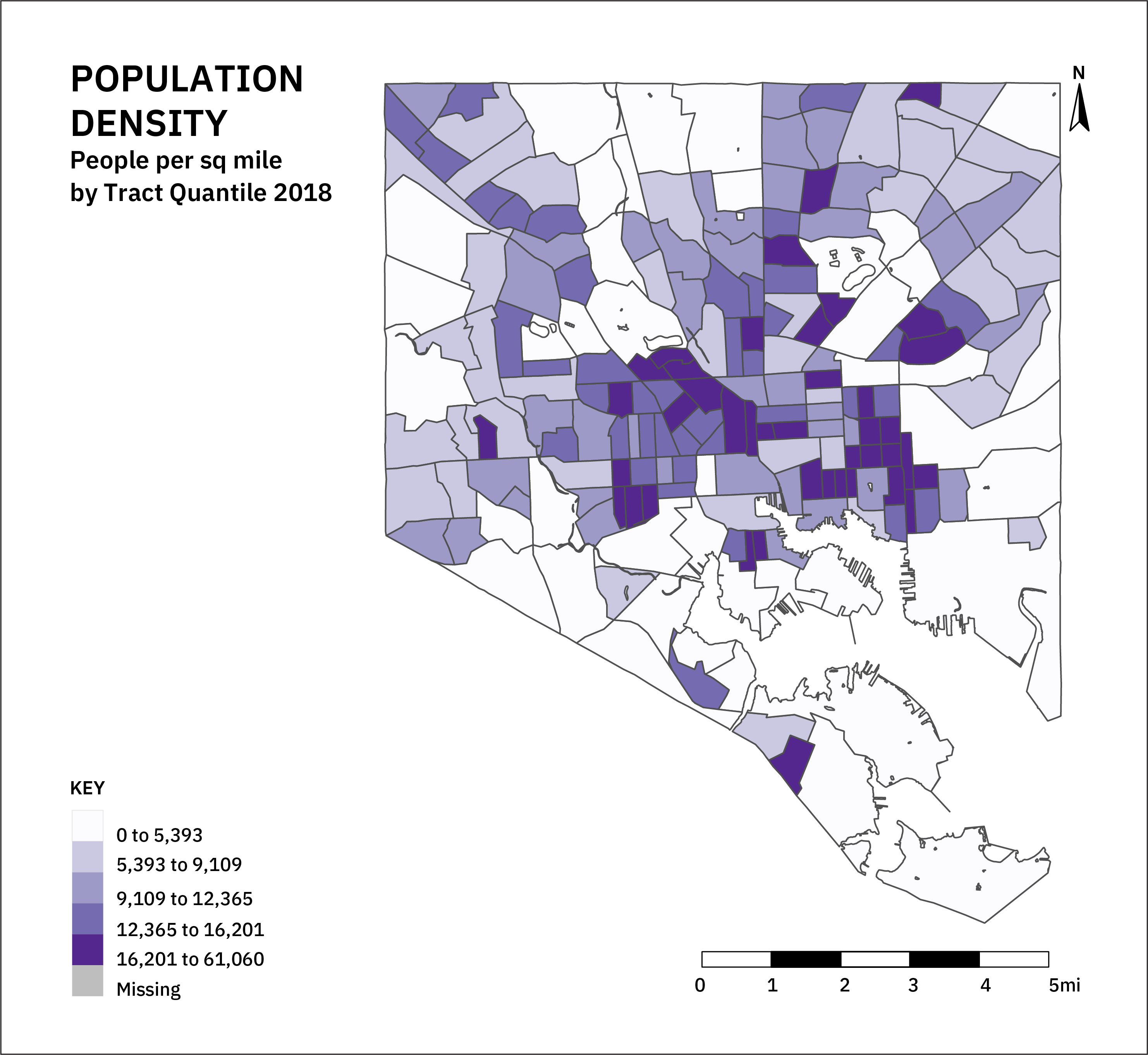

- 7,594 People per sq. mile

- 6.45% Forest cover

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome

- 18% Developed open space

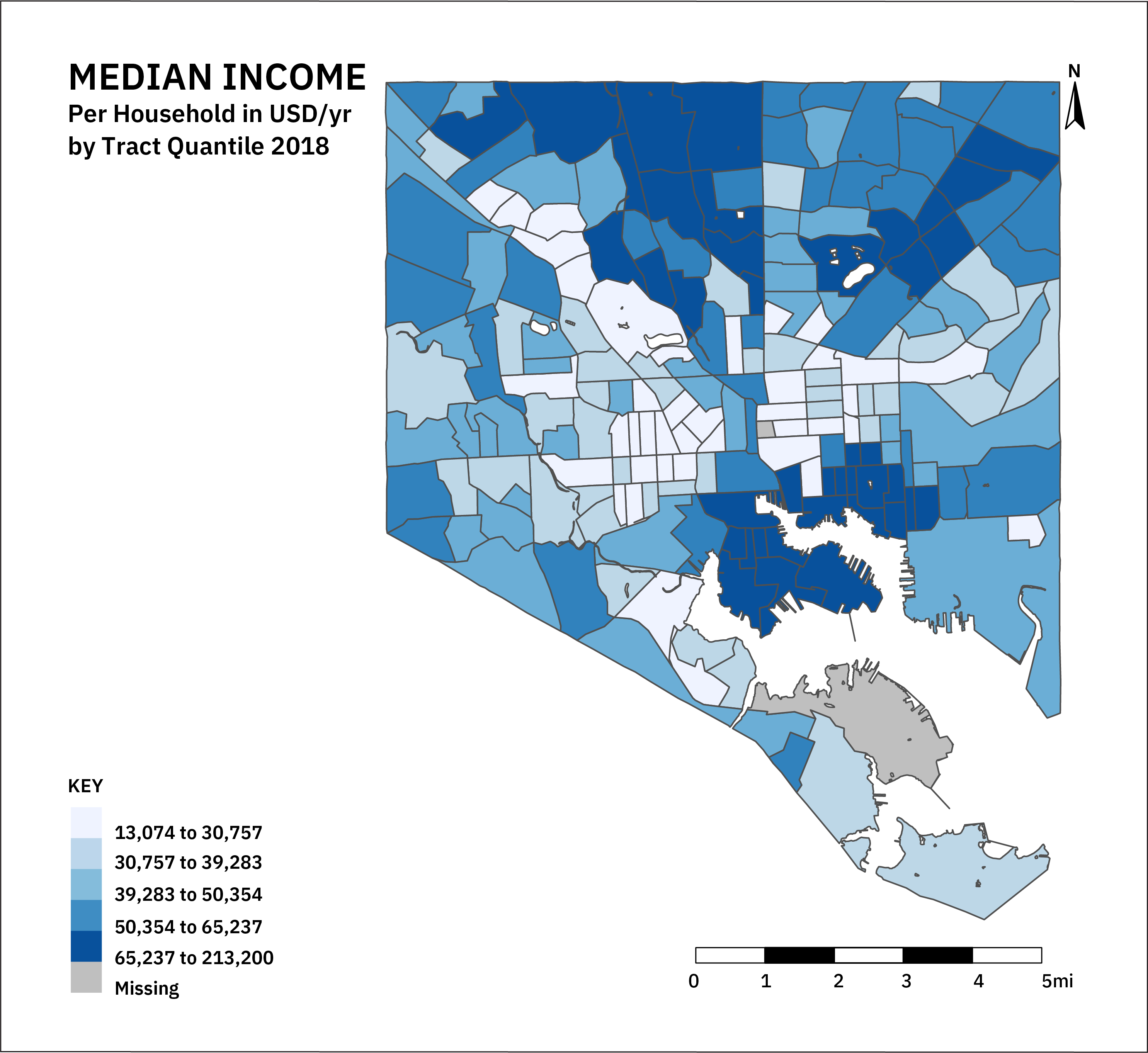

- $48,840 Median household income

- 16.6% Live below the federal poverty level

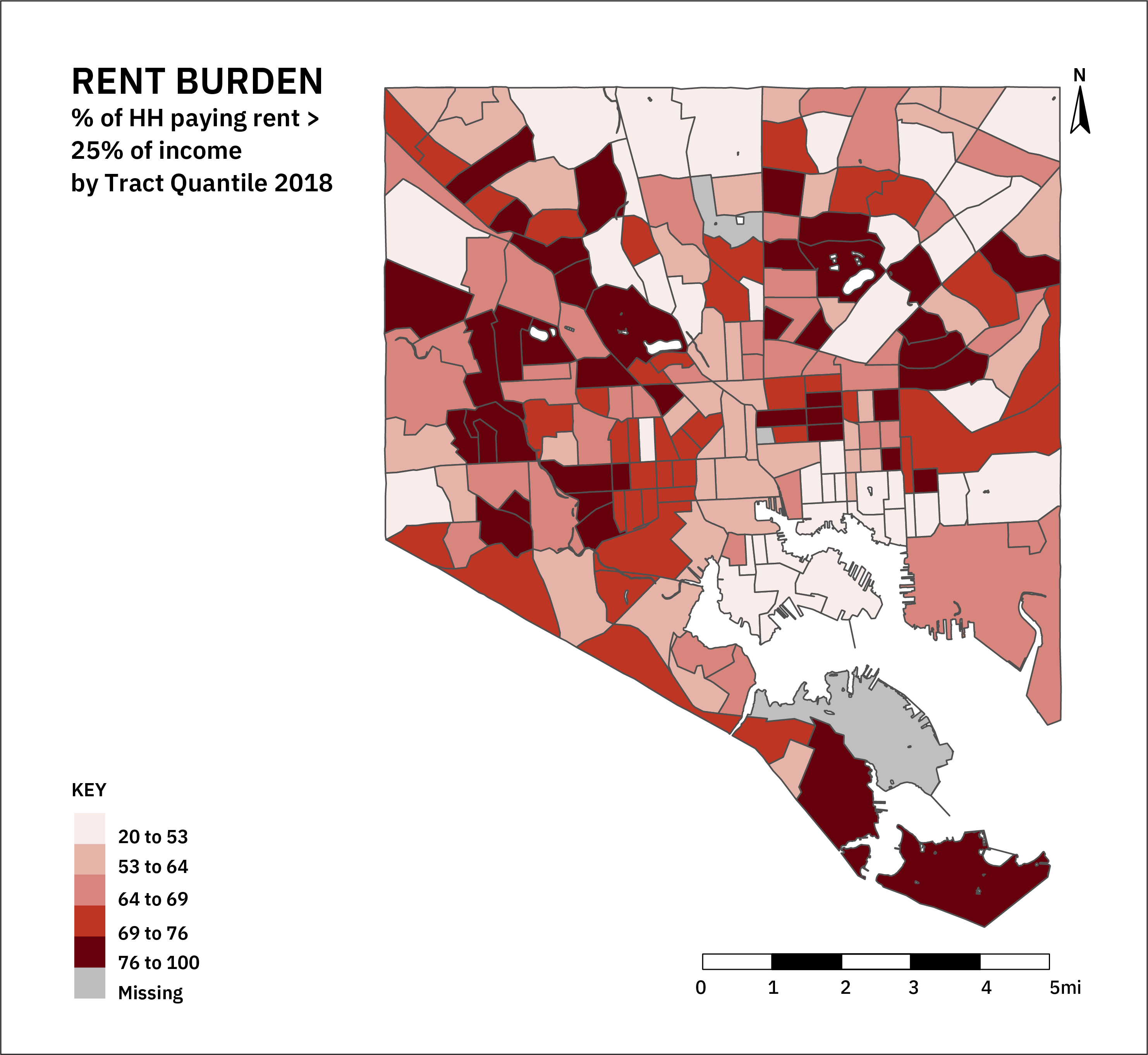

- 64% Estimated rent-burdened households

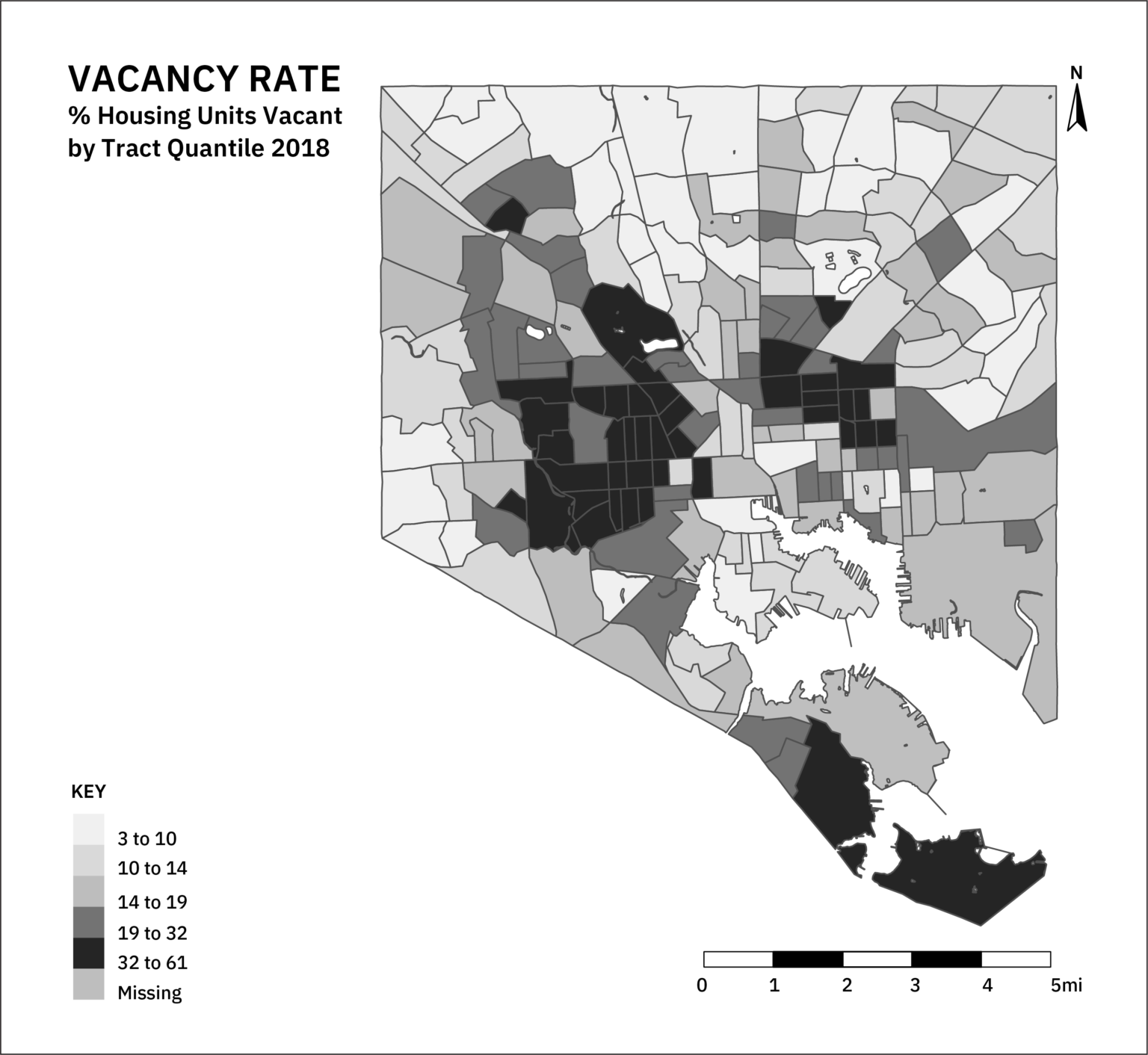

- 19% Housing units vacant

- 0.2% Native, 27.5% White, 61.8% Black, 5.3% Latinx , 0.1% Multi-racial/’other,’ 2.6% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander

*socioeconomic data estimates are from 5-year ACS data from 2018, racial composition from ACS 2019, and land cover data from 2016 NLCD

CITY CONTEXT

Baltimore occupies the homelands of several bands of Piscataway peoples who were forcibly removed but persist in the region to this day. Currently the city has a thriving Native community and cultural center. “America’s Greatest City” has long served as a flashpoint for numerous social movements for racial and socio-economic equality and justice. These movements offer equitable visions for the future of the city to counter waves of racialized disinvestment, reinvestment, and population decline. The city has lost over a third of its population since 1950, a trend coinciding with steady population growth in the broader metropolitan region.

Baltimore has made large investments in its waterfront area in the last several decades and seeks to reinvent many of the city's vacant parcels. A key question remains as to how such initiatives will build the wealth of marginalized residents amidst ongoing struggles for justice and large disparities in green space access and environmental quality.

Green Infrastructure in Baltimore

The majority of GI plans in Baltimore deal with stormwater management, although ambitious city-wide efforts, such as the Green Network Plan, supported by the Sustainability Plan, seek to unify a larger number of landscape elements in a broader push for urban redevelopment. Like many other cities, several plans utilizing the GI concept do not define it, including the MS4 and TMDL WIP, Inner Harbor 2.0, and S. Baltimore Gateway Master Plans.

Broadly, plans do not differ substantially in the types of elements considered green infrastructure, although definitions of GI omit the use of green materials and technology, focusing on ecosystems and hybrid facilities. Only plans utilizing landscape concepts include parks and gardens.

GI is primarily managed to provide environmental functions and is often dominated by a diverse array of hydrological services with a lesser emphasis on air quality.

Baltimore plans focus on the socio-economic benefits of GI with a limited focus on environmental and technological benefits. Two plans in particular – the Sustainability Plan and the Healthy Harbor Plan – seek to provide a wide array of social and ecological benefits.

Key Findings

GI Plans in Baltimore commonly refer to the need to address equity and justice concerns, and yet equity remains poorly defined, with few binding mechanisms for equitable design, implementation, and evaluation. GI implementation is widespread and occurs alongside city-wide efforts for greening and urban renewal.

Of the plans in our analysis...

82%

explicitly refer to equity, 100% have equity implications

9%

attempt to integrate landscape and stormwater concepts

82%

seek to address climate and other hazards

36%

apply a lens of universal good to GI

18%

define equity

63%

explicitly refer to justice

100%

claim engagement with affected communities in planning

18%

recognize that some people are more vulnerable than others

0%

mention Native peoples or relationships with land

Baltimore through Maps

Like many older East Coast cities, Baltimore is characterized by high density, a relatively small amount of open space, and a high degree of rent burden. The scars of targeted disinvestment can still be seen in the distributions of vacancy and income. A dense urban core is divided into distinct neighborhoods connected to income level. More affluent neighborhoods are clustered around the Inner Harbor, which has seen extensive redevelopment. Green space is unevenly distributed, with more green found in higher-income suburbs and in larger city parks.

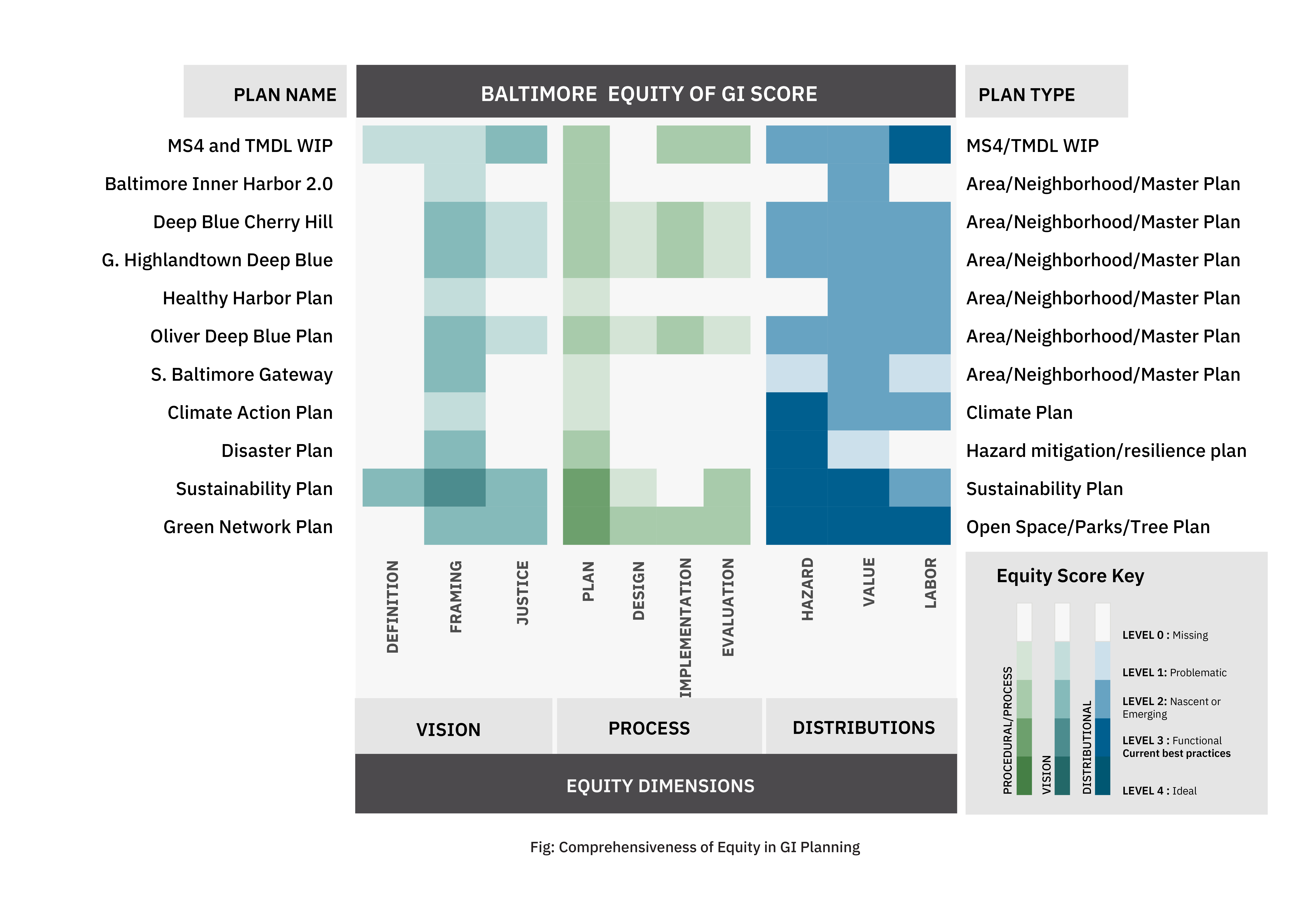

How Does Baltimore Account for Equity in GI Planning?

While many plans make significant commitments to equity and inclusion, few mechanisms exist for community involvement throughout the GI lifecycle. No plan in Baltimore accounts for equity across our ten equity dimensions.

We only found two definitions of equity across 11 plans, and although the Sustainability Plan seeks to address historical oppression, it only briefly discusses how city policies and programs have contributed to environmental and social injustice.

Mirroring our broader findings, there are significant equity implications for how the city plans to use GI to manage urban hazards and rearrange the value of the urban landscape. Several plans have devoted considerable space to discussing the equity implications of city-wide and neighborhood-specific GI initiatives, though no protocols were put forth to address potential housing displacement.

Envisioning Equity

Only the Sustainability Plan and the MS4 and TMDL WIP define equity. The MS4 plan also applies a frame of universal good to its stormwater-focused GI programs. Across several plans, despite the recurring use of the word justice, we found no real elaboration of the concept, with equity framings preferring to focus on improving current conditions rather than addressing the need for restorative actions. These efforts tend to represent injustices as historical without acknowledging their perpetuation today. The exceptions to this are the Green Network and Sustainability Plans.

Procedural Equity

Despite many commitments to involve communities in GI planning, few substantive mechanisms for including communities through the planning lifecycle could be found. Some exceptions include the Sustainability and Green Network Plans, although the Sustainability Plan lacks sufficient mechanisms for truly equitable implementation. Almost half the plans examined had no procedures for including communities post planning. Several included processes for community engagement that were insufficient, including limited spot surveys, which stood in for more meaningful and comprehensive community input - despite claims to equity elsewhere in the plans. Overall, while plans tout a diverse array of community benefits, their metrics of success are often too simple, if not problematic, and do not include substantive avenues for communities to evaluate plan outcomes.

Distributional Equity

All plans addressing GI in Baltimore seek to improve the value of the urban landscape in multi-dimensional ways. Likewise, almost all plans seek to mitigate urban hazards, despite a limited acknowledgment of the different vulnerabilities to hazards and their uneven spatial distributions. The exceptions are the Disaster Preparedness, Sustainability, and Green Network Plans. In terms of the distribution of labor, many plans expressly and problematically rely on volunteer labor from affected communities for the success of GI programs, although a few underscore the need for workforce development and expanded hiring to meet GI goals.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

There are many opportunities to improve the equity of GI planning in Baltimore especially given an ongoing effort by the City of Baltimore to apply an equity lens to all of its municipal agencies’ activities. While a deeper analysis of implementation equity is ongoing, Baltimore already has a diverse array of non-governmental stakeholders, both nonprofit and private, involved in GI planning and implementation. Like other cities, targeted investments in GI coupled with city incentives to attract real estate capital for urban redevelopment pose significant risks of displacement. Yet the city has a very real need to build community and intergenerational wealth in oppressed communities while improving long-standing environmental hazards.

Community Groups

Baltimore is home to many robust social movements and community organizations that do not appear well represented within current GI planning efforts. While the immediate and pressing concerns that many of these organizations face do not appear closely related to GI, a community’s infrastructure assets form the underlying basis for its material and social well-being. Given the capacity of comprehensive GI planning to address persistent environmental injustices, a greater emphasis could be placed on using public resources and planning efforts to support the intersectional goals of existing community organizations. However, planning fatigue has been noted in Baltimore, so efforts must be focused on those areas where positive impacts can be delivered.

1. The Need for Substantive and Transparent Community Engagement

Current planning practices in Baltimore have almost no mechanisms for community-based evaluation of the implementation of GI plans, although some updates promise the creation of community forums for evaluation. Given the broader trend towards inclusive planning and the use of an equity lens and ordinance in the city (see below), community groups should advocate and organize actions to create transparent and binding mechanisms.

2. From Increasing Value to Transformative Justice

While Baltimore has a high rate of housing vacancy, it is unclear to what extent this can be addressed through existing and largely speculative market mechanisms. Prior efforts to attract external investment have led to infamous levels of displacement from the Inner Harbor. Existing conversations on alternative means of wealth building and community ownership of land need to translate into transformed institutional procedures to deliver redistributive justice. Community groups should demand new forms of decision-making through which their needs and concerns can be met by city agencies. Part of creating such processes should include dedicated resources for community-led planning and projects.

3. Mechanisms to Hold Planners Accountable

Many communities are experiencing planning fatigue in Baltimore. In this climate, several community-led plans created initiatives seeking to redevelop areas for regional real estate markets in contradiction to significant expressions of concern by members of the affected communities. Such was the case in the Deep Blue Cherry Hill plan. Planners must be held accountable, but the burden of enforcement must not fall to community members. Community advocates must be able to focus organizing efforts on projects and programs that meet their needs.

Policy Makers and Planners

While many nonprofit actors are involved in implementing green stormwater infrastructure facilities, the larger push for GI and associated policy instruments and initiatives has largely come from city policy makers and planners responding to federal and state regulations. With a recent Baltimore City ordinance requiring city agencies to consider their contributions to historical and ongoing patterns of injustice, it would be timely for city actors to initiate changes in standard operating procedures and planning models.

1. Being Clear on What Equity Is, and Is Not

Despite a prolific use of the word, few city plans concretely define equity and its broader framing remains highly problematic. Following community calls for justice, like those from Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle and Black Lives Matter, there is a profound need to clarify and expand the framing of equity with agency planning and policy makers to address the long-standing concerns of city residents. Policy makers can continue to embrace methods of public engagement that do not rely on public meetings while drawing upon established principles of community inclusion (like the Jemez Principles). A greater diversity of voices in formal institutions will allow for more concrete and meaningful framings of equity and justice in city plans.

2. From Words to Action

Similar to many other cities, planners and policy makers need to move beyond discussing equity concerns in plans and move towards creating binding statutory and regulatory mechanisms for community inclusion in plan formulation and evaluation. Given that equity issues run deep, there should be greater emphasis on structural reform (e.g. reorganizing formal decision-making bodies and public financial institutions) rather than focusing only on the distribution of environmental goods and services. Processes for community inclusion in planning must also become more transparent to show whether residents affected by plans had a real say in shaping them.

3. Redistributing Decision Making Requires Redistributing Labor and Resources

The current equity ordinance enacted in 2018 in Baltimore City tasks each city agency with hiring an Equity Coordinator. The shift towards community involvement and equity in GI programs likewise created limited positions for agencies to liaise with communities in the course of implementing watershed improvement projects. While promising, these tools have fallen short of leading to any structural changes within standard operating procedures and generally have not included binding processes to make such changes. The city should invest in mechanisms for communities to conduct such assessments themselves, including the formulation of equity assessments.

Foundations and Funders

Existing nonprofits have contributed heavily to GI deployment and planning within Baltimore and some mechanisms for dedicated maintenance support and community labor have led to favorable outcomes. In other cases, poorly tracked outcomes and limited community engagement have led to numerous problems in facility maintenance and inequitable burdens of GI. Importantly, significant opportunities exist to support community-led efforts in developing institutional tools that will embed more equitable procedures and funding in GI and related community revitalization efforts.

1. Supporting Intersectional Organizing

Dedicated funding for community organizing around environmental, housing, and social justice should support community-led initiatives already addressing those intersectional challenges. Piecemeal and project-based funding can contribute to a culture of scarcity and competition, and can undermine more cohesive efforts for community organizing.

2. Seizing Opportunities for Structural Change

Increasing dedicated resources for community-led initiatives working to influence the implementation of Baltimore’s equity ordinance allows organizers an opportunity to contribute to a historic reformulation of how municipal governments operate on a day to day basis. Piecemeal funding models are unlikely to contribute to such a structural and operational shift. In addition, a greater emphasis should be placed on hosting broad community forums and other inclusionary mechanisms.

3. Rethinking and Remaking Urban Form - A Green New Deal for Baltimore?

Paradoxically, Baltimore has a very high vacancy rate and relatively high population density compared to other US cities. While initiatives to ‘green’ vacant lots (and demolish vacant buildings) are fairly well developed, these do not appear to be well integrated into the broader economic transformation required for redistributing wealth to disenfranchised communities. Foundations and funders should collaborate with communities and city agencies for a larger scale rethink around the functions and benefits of green infrastructure in the context of transformative structural economic programs like a municipal 'green new deal' – a concept that other municipalities are contemplating. Larger scale analyses of runoff, social and environmental inequality, and housing needs may yield insight into how other parts of the city can be redeveloped to improve economic and housing justice while making space for nature and climate resilience solutions.

Closing Insights

Planning for equity in green infrastructure requires a deep rethinking and restructuring of urban governance to build wealth and value for communities while addressing historical and ongoing harms. Baltimore has opportunities to address its long-standing inequalities in exposure to environmental hazards, employment opportunities, policing, and education, but these opportunities require significant structural change in city institutions and agency priorities.

Resources

A public access repository of all 122 Urban plans from 20 US cities analyzed, along with key metrics for each plan organized in a spreadsheet.

Peer-reviewed publications, blog articles, and other writing produced by the team related to this study.

Definitions for terms commonly used on this website and throughout the project.